New Winged Dinosaur May Have Used Its Feathers to Pin Down Prey

Meet “the Ferrari of raptors,” a lithe killing machine that could have taken down a young T. rex

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3a/79/3a791e09-210b-4a62-9a8d-75fa284bc338/dakotaraptor-human.jpg)

A newly discovered winged raptor may have belonged to a lineage of dinosaurs that grew large after losing the ability to fly. But being grounded likely didn't stop this sickle-clawed killer from making good use of its feathered frame—based on the fossilized bones, paleontologists think this raptor could have used the unusually long feathers on its arms as a shield or to help pin down squirming prey.

Dubbed Dakotaraptor steini, the Cretaceous-era creature was found in South Dakota in the famous Hell Creek Formation, which means it shared stomping grounds with Tyrannosaurus Rex and Triceratops around 66 million years ago. Measuring about 17 feet long, Dakotaraptor is one of the largest raptors ever found and fills a previously vacant niche for medium-sized predators in the region.

Paleontologists had suspected a creature might be found to fill this body-size gap, but "we never in our wildest dream imagined it would be a raptor like this," says study coauthor Robert DePalma, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Palm Beach Museum of Natural History. "This is the most lethal thing you can possibly throw into the Hell Creek ecosystem."

Based on the Dakotaraptor skeleton, DePalma and his team surmise that the animal had a lean and lithe body that excelled at running and jumping. "Dakotaraptor was probably the fastest predator in the entire Hell Creek Formation," DePalma says. "It was the Ferrari of raptors."

Its speed, combined with a giant sickle-like killing claw on each foot, would have made Dakotaraptor a formidable adversary. “It could have given a juvenile T. rex a run for its money, and a pack of them could have taken on an adult T. rex,” DePalma says.

This deadly capability means the raptor, described online this week in the journal Paleontological Contributions, has scientists rethinking their notions about the ecology of the region. "It's like getting all the facts we've ever had about the predator-prey relationships in Hell Creek and shaking them all up in a bag," DePalma says.

Philip Manning, a paleontologist at the University of Manchester in the U.K. who was not involved in the study, agrees. "The presence of this major new predator would have undoubtedly had a huge impact on the dynamics of the Late Cretaceous ecosystem," Manning says in an email. Its discovery "shows that we have much still to learn about this period of time that is the last gasp of the age of the dinosaurs.”

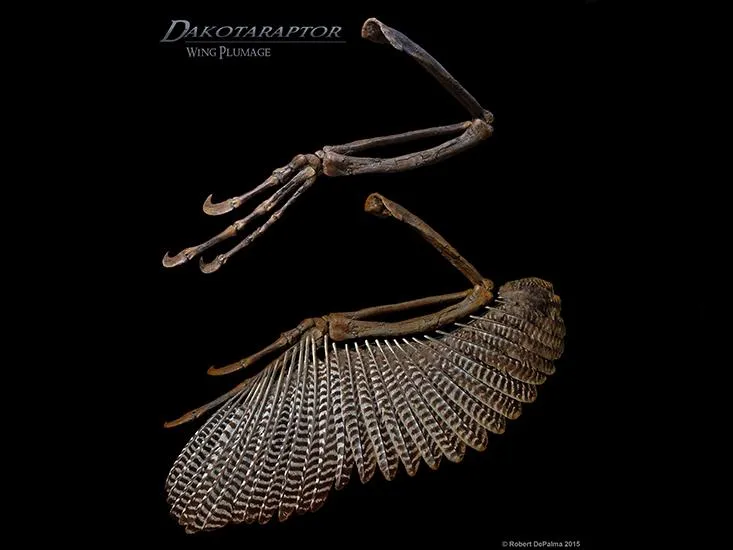

One of the most striking features of the Dakotaraptor fossil is a series of tiny bumps on its forearm, which DePalma's team has identified as quill knobs. Found on many modern birds, these bony nubs serve as fortified attachment sites for long wing feathers. "Dakotaraptor is the first large raptor found that has physical evidence of quill knobs," DePalma says. "When you see quill knobs, it tells you that the animal was serious about using those feathers."

The bone structure of Dakotaraptor's arm also bears a striking resemblance to the wing structure of modern birds. "We can use the word 'wing' correctly here even though it was too big to fly," DePalma says.

But if it wasn’t capable of flight, why did Dakotaraptor need wings and quill knobs? "These things don't appear overnight, and evolutionarily you don't evolve features like that without a reason," DePalma adds.

One intriguing possibility is that Dakotaraptor was part of a lineage of dinosaurs that once had the ability to fly but then lost it. "When things become flightless, you generally see them become big," DePalma says. "You saw it with moas and terror birds, and you see it with ostriches today. Dakotaraptor could have essentially been a lethal paleo-ostrich."

However, Manning thinks a more likely possibility is that Dakotaraptor belonged to a group of theropod dinosaurs that was laying the groundwork for flight but had not yet taken that final leap into the skies.

In either scenario, the flightless Dakotaraptor could still have found uses for its wing feathers, DePalma says. For example, the animal could have used them to frighten or impress other dinosaurs or to pin down prey—both are strenuous activities that would require strong feather attachments. Alternatively, Dakotaraptor could have used its wings to shield its young.

"Some hawks will form a kind of tent over their chicks to shield them from the weather or the sun," DePalma says. "If you imagine a dozen squirming baby raptors that have the energy and tenacity of kittens knocking into your wings, then that could warrant quill knobs as well."