Ocean Dead Zones Are Getting Worse Globally Due to Climate Change

Warmer waters and other factors will cause nearly all areas of low oxygen to grow by the end of the century

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/96/14/96149c80-3b68-426b-80b3-f2db3d3fd606/phytplanktonbloom.jpg)

Nearly all ocean dead zones will increase by the end of the century because of climate change, according to a new Smithsonian-led study. But the work also recommends how to limit risks to coastal communities of fish, crabs and other species no matter how much the water warms.

Dead zones are regions where the water has unusually low dissolved oxygen content, and aquatic animals that wander in quickly die. These regions can form naturally, but human activities can spark their formation or make them worse. For instance, dead zones often occur when runoff from farms and cities drains into an ocean or lake and loads up the water with excess nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus. Those nutrients feed a bloom of algae, and when those organisms die, they sink through the water column and decompose. The decomposition sucks up oxygen from the water, leaving little available for fish or other marine life.

Researchers have known that low-oxygen, or hypoxic, areas are on the rise. They have doubled in frequency every 10 years since the 1960s, largely due to increases in nutrient-filled runoff. But warming and other aspects of climate change will likely worsen dead zones around the world, argue Andrew Altieri of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama and Keryn Gedan of the University of Maryland, College Park, and the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center in Maryland.

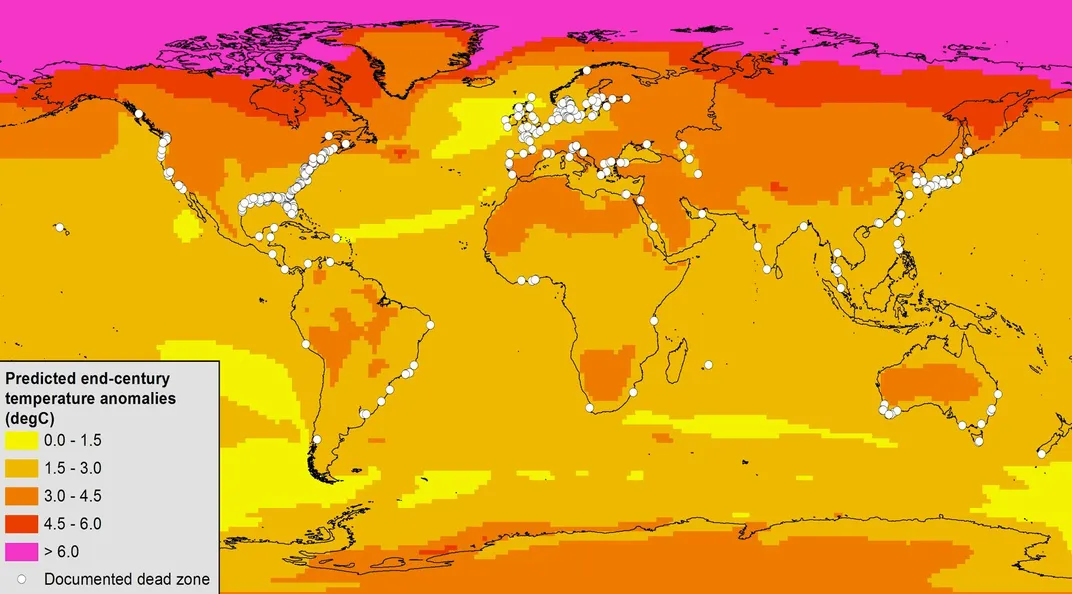

“Climate change will drive expansion of dead zones, and has likely contributed to the observed spread of dead zones over recent decades,” Altieri and Gedan write in a new paper that appears today in Global Change Biology. The researchers examined a database of more than 400 dead zones worldwide. Some 94 percent of these hypoxic areas will experience warming of 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit or more by the end of the century, they found.

“Temperature is perhaps the climate-related factor that most broadly affects dead zones,” they note. Warmer waters can hold less dissolved oxygen in general. But the problem is more complicated than that. Warmer air will heat up the surface of the water, making it more buoyant and reducing the likelihood that the top layer will mix with colder waters below. Those deeper waters are often where the hypoxia develops, and without mixing, the low-oxygen zone sticks around.

As temperatures increase, animals such as fish and crabs require more oxygen to survive. But with less oxygen available, “that could quickly cause stress and mortality and, at larger scales, drive an ecosystem to collapse,” Altieri and Gedan warn.

Other aspects of climate change could further exacerbate dead zones. In the Black Sea, for instance, the earlier arrival of summer has resulted in the earlier development of hypoxia as well as expansion of the dead zone area. And sea level rise will devastate wetlands, which for now help to defend against the formation of algal blooms by soaking up excess nutrients from runoff.

“Climate change can have a variety of direct and indirect effects on ocean ecosystems, and the exacerbation of dead zones may be one of the most severe,” the researchers write. The good news, though, is that the dead zone problem can be tackled by reducing nutrient pollution. With less nitrogen or phosphorus to feed algal blooms, dead zones are less likely to form no matter how warm it gets.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)