The “Pompeii of Animals” Shows Dinosaurs, Mammals and Early Birds in Their Death Throes

A lethal volcanic explosion is identified as the culprit behind a mysterious mass death of creatures that took place around 125 million years ago

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/26/81/26819ca6-7b4f-47ce-81bf-f69e15742043/animals.jpg)

Around 125 million years ago, northern China and southeast Mongolia was a flourishing mix of coniferous pine forests, wetlands and lakes. Mammals lived alongside feathered dinosaurs, and a diversity of birds, fish, lizards and turtles populated the sky, trees and waterways. Researchers call this Lower Cretaceous ecosystem the Jehol Biota, named after a mythical land from Chinese folklore.

So much is known about the Jehol Biota’s ancient flora and fauna because of exceptionally well-preserved fossils that have turned up in the area over the years. Those millennia-old creatures’ remains—including impressions of body outlines and the textures of feathers, scales or fur imprinted into what was once mud, even fossilized soft tissue—speak of some past calamity that befell the ecosystem, wiping out troves of organisms in one cataclysmic blow.

Previously, researchers floundered between blaming volcanoes or deadly lake gases on the animals’ annihilation. Volcanoes seemed the obvious culprit, and volcanic ash has been found embedded in the fossil layers. On the other hand, the animals themselves often turn up at the bottom of ancient lakes and are partly encased in lake mudstone. Lately, researchers hypothesized that a limnic overrun—a rare type of eruption in which carbon dioxide emerges from a deep lake and asphyxiates all animals in the vicinity—was responsible for the Jehol Biota.

Some researchers from China and the U.S., however, were not entirely convinced by this hypothesis. The animal remains were found heaped together at the sites of former lakes, but a limnic overrun alone wouldn’t have caused animals from near and far to fall into the lake. To solve the mystery, the team examined and chemically analyzed 14 fossil bird and dinosaur specimens collected from five locations around the Jehol Biota area. They studied the sediments found in the fossils, and discovered that the bones all had traces of volcanic materials. The animals’ postures, they further confirmed, supported death by volcano, they report in Nature Communications.

This wasn’t just any eruption, however. Most likely, what killed the Jehol Biota creatures was a pyroclastic density current—a wave of hot gas emitted from a volcano that can move up to 450 miles per hour. Such natural belchings are nature’s equivalent to chemical warfare or an atom bomb: uncompromisingly deadly, destructive and powerful. The gas from those currents can reach temperatures of 1,830 °F and instantly kills any living organism it touches. The heat blast is also strong enough to propel boulders across the ground, which move fast enough to flatten trees. Finally, the deadly display is topped off by a rain of extremely hot ash.

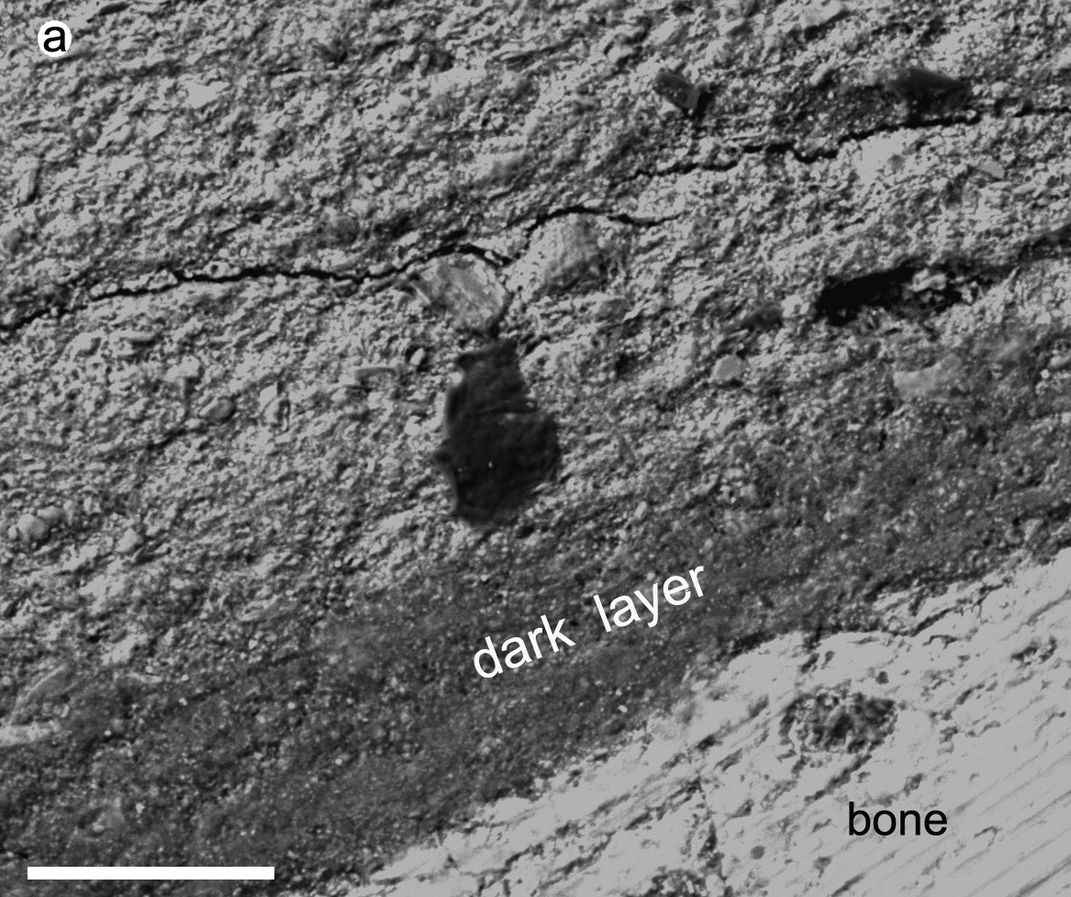

A pyroclastic density current famously annihilated the towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum in 79 AD, and it seems this scenario wreaked havoc on the Jehol Biota, too. The fossilized animals, the researchers write, show “entombment poses” characteristic of being caught in a pyroclastic density current, including flexed limbs and extended spines. These postures “result from postmortem shortening of the tendons and muscles,” they explain. Indeed, the animal victims’ postures match up with those found at more recent volcanic events, such as the 1902 Mount Pelee eruptions. Six of the skeletal remains studied at Jehol Biota also showed a darkening of the bones, which the researchers think is carbonized muscle and skin tissue—a result of the hot ash hitting their bodies.

A pyroclastic density current likewise would explain why the remains tend to be piled together. This phenomenon speaks to “the capacity of pyroclastic density currents to carry their victims and drop their remains far away from where they were engulfed by the pyroclastic density current,” they write. As they were carried along, the animals charred and finally deposited onto the lake floor.

As for the lake, by the time the animal remains arrived it would have been an empty pit. When water—even quite a bit of water—comes into contact with a pyroclastic density current, it evaporates immediately, egging on the blistering flow at an even faster pace than before, now that it is being propelled on a bed of steam.

Overall, the ancient animals’ remains were eerily similar to the victims found at Pompeii, the authors describe:

The fine-grained volcanic ash that encloses the remains probably formed moulds around complete skeletons, resembling the intact, buried corpses at Pompeii.

Fresh, hot, dry, acid volcanic ash promoted burning, charring or mummifying of soft tissues, which, as a result, became more resistant to decay and better preserved. The burnt, charred or mummified organic tissues probably served as templates for the extremely fine-grained ashes that coated them, forming the two- dimensional body outlines.

Carbonized bone surfaces, cracks spreading outwards from haversian canals, fine crisscrossed cracks at bone edges and microstructure absent towards bone surfaces are comparable to features from victims at Pompeii and nearby archaeological sites caught in [pyroclastic density currents] from the 79 AD eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. Similarly, these characteristics are consistent with experimental results from heating modern bones.

All evidence, they conclude, points to the following scenario: the animals living in the Jehol Biota were overtaken by a sudden pyroclastic density current blast, which killed them instantly and transported their scorched bodies in heaps onto the evaporated lakes’ floors, where those remains spent the next 120 to 130 millennia contorted in their death throes.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)