Preserving Silence in National Parks

A Battle Against Noise Aims to Save Our Natural Soundscapes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/parks_631.jpg)

The preservation of natural sounds in our national parks is a relatively new and still evolving project. The same can be said of our national parks. What Wallace Stegner called "the best idea we ever had"* did not spring full grown from the American mind. The painter George Catlin first proposed the park idea in 1832, but it was not until 1872 that Yellowstone became the first of our current 391 parks. Only much later did the public recognize the park's ecological value; the setting aside of Yellowstone had more to do with the preservation of visually stunning natural monuments than with any nascent environmentalism. Not until 1934, with the establishment of Everglades, was a national park instituted for the express purpose of protecting wildlife. And not until 1996 was Catlin's vision of a prairie park of "monotonous" landscape, with "desolate fields of silence (yet of beauty)," realized in Tall Grass Prairie National Preserve in Kansas.

As one more step in this gradual evolution, the Park Service established a Natural Sounds Program in 2000 with the aim of protecting and promoting the appreciation of park soundscapes. It would be a mistake to think of this aim as having originated "on high." In a 1998 study conducted by the University of Colorado, 76 percent of the Americans surveyed saw the opportunity to experience "natural peace and the sounds of nature" as a "very important" reason for preserving national parks.

But noise in parks, as in society at large, is on the rise—to the extent that peak-season decibel levels in the busiest areas of certain major parks rival those of New York City streets. Airplanes, cars, park maintenance machinery, campground generators, snowmobiles, and personal watercraft all contribute to the general commotion. The more room we make for our machines, the less room—and quiet—we leave for ourselves.

*Apparently Stegner was not the first to think so. In 1912 James Bryce, the British ambassador to the United States, said that "the national park is the best idea American ever had."

__________________________

Several times I heard park officials refer to the Natural Sounds office in Fort Collins, Colorado, as "Karen Trevino's shop," a good description of what I found when I stepped through the door. Cases of sound equipment—cables, decibel meters, microphones—were laid out like a dorm room's worth of gear on the hallway carpet, not far from several bicycles that staffers, most of them in their 20s, ride to work. A few members of the team were preparing for several days of intensive work out in the field. As animated as any of them was Karen Trevino.

"If the mayor of New York City is trying to make what people expect to be a noisy place quieter," she said, referring to the Bloomberg administration's 2007 revision of the city noise code, "what should we be doing in places that people expect to be quiet?"

As a step toward answering that question, Trevino and her crew calibrate sound level information and convert it into color-coded visual representations that allow a day's worth of sound levels, and even an entire park's sound profile, to be seen at a glance. (Probably by the beginning of 2009 readers will be able to see some of these profiles at http://www.westernsoundscape.org.) The technicians also make digital sound recordings to develop a "dictionary" by which these visual depictions can be interpreted. Much of their research is focused on creating plans to manage the roughly 185,000 air tours that fly over our parks each year—a major mandate of the National Parks Air Tour Management Act of 2000. The team is currently working on its first proposal, for Mount Rushmore, a 1200 acre unit with 5600 air tour overflights a year. Franklin Roosevelt once called this park "the shrine of democracy."

"When you think about it," Trevino says, "what's the highest tribute we pay in this country—really, in the world—of reverence and respect? A moment of silence. Now, that said, nature isn't silent. It can be very noisy. And people in parks aren't quiet all the time." Neither are things like cannon in a historical park like Gettysburg—nor should they be, according to Trevino. "Our job from a public policy standpoint is asking what noises are appropriate, and if they're appropriate, are they at acceptable levels?"

Trevino sees this as a learning process, not only for her young department but also for her. Some of what she's learned has passed to her private life. Recently she asked her babysitter to stop using the terms "indoor voice" and "outdoor voice" with her young children. "Sometimes it's perfectly appropriate to scream when you're indoors and to be very quiet when you're outdoors," she says.

____________________________________________________

Though much remains to be done, the Park Service has already made significant progress in combating noise. A propane-fueled shuttle system in Zion National Park has reduced traffic jams and carbon emissions and also made the canyon quieter. In Muir Woods, library-style "quiet" signs help keep the volume down; social scientists have found (somewhat to their surprise) that the ability to hear natural sounds—15 minutes away from San Francisco and in a park celebrated mostly for the visual magnificence of its trees—ranks high with visitors. In Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, which have a major naval air station to the west and a large military air training space to the east, park officials take military commanders on a five-day "Wilderness Orientation Overflight Pack Trip" to demonstrate the effects of military jet noise on visitor experience in the parks. Before the program started in the mid-1990s, rangers reported as many as 100 prohibited "low flier" incidents involving military jets every year. Now the number of planes flying less than 3000 feet above the ground surface is a fourth to a fifth of that. Complaints are taken seriously, especially when, as has happened more than once, they're radioed in by irate military commanders riding on jet-spooked pack horses on narrow mountain trails. In that context, human cursing is generally regarded as a natural sound.

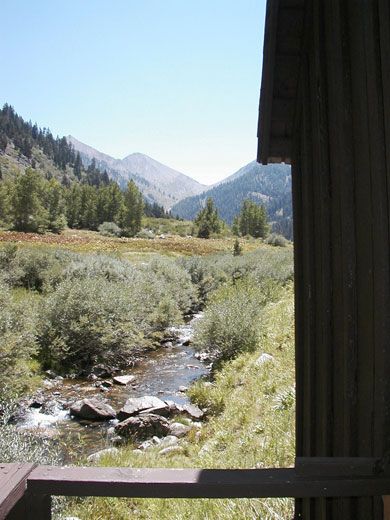

Sometimes the initiative to combat noise has come from outside the park system. Rocky Mountain National Park, for example, has the distinction of being the only one in the nation with a federal ban on air tour over-flights, thanks mostly to the League of Women Voters chapter in neighboring Estes Park. Park Planner Larry Gamble took me to see the plaque the League erected in honor of the natural soundscape. It was in the perfect spot, with a small stream gurgling nearby and the wind blowing through the branches of two venerable aspens. Gamble and I walked up a glacial moraine to a place where we heard wood frogs singing below us and a hawk crying as it circled in front of snow-capped Long's Peak. But in the twenty minutes since we'd begun our walk, Gamble and I counted almost a dozen jets, all in audible descent toward the Denver airport. I'd flown in on one of them the day before.

The most intractable noise problem in our national parks comes from the sky. The reasons for this are both acoustical, in terms of how sound propagates from the air, and political. The skies above the parks are not managed by parks. All commercial air space in the US is governed by the Federal Aviation Administration, which has a reputation for safeguarding both its regulatory prerogatives and what is often referred to in aviation parlance as "the freedom of the skies." Passengers taking advantage of that freedom in the United States numbered around 760 million last year. But much of the controversy about aircraft noise in our parks has centered on air tours.

A twenty-year dispute over air-tours above the Grand Canyon has involved all three branches of the federal government and, for protraction and difficulty, makes the court case in Bleak House look like a session with Judge Judy. A breakthrough seemed likely when the Grand Canyon Working Group, which includes representatives of the Park Service, the FAA, the air tour industry, environmental organizations, tribal leaders, and other affected parties, eventually managed to agree on two critical points. First, the Park Service's proposal that "the substantial restoration of natural quiet" called for in the 1987 Grand Canyon Overflights Act meant that 50 percent or more of the park should be free of aircraft noise 75 percent or more of the time (with no limits established for the other 50 percent). They also agreed on the computer model of the park's acoustics that would be used to determine if and when those requirements had been met. All that remained was to plug in the data.

The results were startling. Even when air tour overflights were factored out entirely, the model showed that only 2 percent of the park was quiet 75 percent of the time, due to noise from hundreds of daily commercial flights above 18,000 feet. In other words, air tours could be abolished altogether and the park would still be awash in the noise of aviation. Those findings came in over two years ago. The Park Service has since redefined the standard to apply only to aircraft flying below 18,000 feet. The Working Group has yet to meet this year.

____________________________________________________

Noise can be characterized as a minor issue. The pollution of a soundscape is hardly as momentous as the pollution of the seas. But the failure of an animal to hear a mating call—or a predator—over a noise event is neither insignificant nor undocumented. (One 2007 study shows the deleterious effects of industrial noise on the pairing success of ovenbirds; another from 2006 shows significant modifications in the "antipredator behavior" of California ground squirrels living near wind turbines.) On the human side, the inability of a park visitor to hear 10 percent of an interpretative talk, or the inability to enjoy natural quiet for fifteen minutes out of an hour's hike—as the Grand Canyon plan allows—does not mean that the visitor understood 90 percent of the presentation or that the hiker enjoyed her remaining forty-five minutes on the trail.

In dismissing the effects of noise, we dismiss the importance of the small creature and the small human moment, an attitude with environmental and cultural costs that are anything but small. Not least of all we're dismissing intimacy: the firsthand knowledge and love of living things that can never come exclusively through the eye, the screen, the windshield—or on the run. This struck home for me in a chat with several members of the League of Women Voters in a noisy coffee house in Estes Park, Colorado. I'd come to learn more about the air tour ban over Rocky Mountain National Park and ended by asking why the park and its natural sounds were so important to them.

"Many people just drive through the park," said Helen Hondius, straining to be heard above the merciless grinding of a latte machine, "so for them it's just the visual beauty." For Hondius and her friends, however, all of whom walk regularly over the trails, the place needed to be heard as well as seen. "It's like anything else," Lynn Young added, "when you take the time to enjoy it, the park becomes a part of what you are. It can shape you."

Robert Manning of the University of Vermont has worked with the park system for three decades on issues of "carrying capacity"—the sustainable level of population and activity for an environmental unit—and more recently on issues of noise. He feels that the park system should "offer what individuals are prepared for at any given stage in their life cycle." In short, it should offer what he calls "an opportunity to evolve." He admires people "who've developed their appreciation of nature to the extent that they're willing and anxious to put on their packs and go out and hike, maybe for a day, maybe for a two-week epic adventure, walking lightly on the land, with only the essentials. But—those people probably didn't start there. I bet a lot of them went on a family camping trip when they were kids. Mom and Dad packed them into the car in the classic American pilgrimage and went out for two weeks' vacation and visited fifteen national parks in two weeks and had a wonderful time."

Seen from Manning's perspective, the social task of the national parks is to provide an experience of nature that is both available to people as they are and suitable to people as they might become. Such a task is robustly democratic and aggressively inclusive, but it is not easily achieved. It obliges us to grow, to evolve as the parks themselves have evolved, and we may best be able to determine how far we have come by how many natural sounds we can hear.

Garret Keizer is at work on a book about the history and politics of noise. You can contribute a story to his research at: www.noisestories.com.