Will the Public Ever Get to See the “Dueling Dinosaurs”?

America’s most spectacular fossil, found by a plucky Montana rancher, is locked up in a secret storage room. Why?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/59/99/59990716-6828-483d-b281-aa77e2a5f442/julaug2017_b22_hellcreekdinos.jpg)

The Dinosaur Cowboy sits behind an old desk in the dusty basement workshop of the ranch house where he grew up, wearing a denim shirt and blue jeans, his thinnish brown hair bearing the impression of his black Stetson, which he’s left upstairs in the mudroom, along with his boots. Behind him, peering down over his shoulder from its perch atop an antique safe, is the fearsome, dragon-like head of a horned Stygimoloch, a replica of an important fossil he once found. The way it is mounted, jaws agape, it appears to be smiling, captured in a moment of prehistoric mirth.

The Dinosaur Cowboy is smiling, too. You could probably say it’s an ironic smile, or a little bit of a grimace. His real name is Clayton Phipps. A wiry 44-year-old with a weathered yet impish face, he lives on the ranch with his wife, two sons, a few horses and 80 cows in the unincorporated community of Brusett, Montana. Located in the far north of the state, near the rim of the Missouri River Breaks, it is all but impassable during winter; the closest shopping mall is 180 miles southwest, in Billings. Of his spread, Phipps likes to say: “It’s big enough to not starve to death on.”

Phipps is the great-grandson of homesteaders—pioneers who were given the right to claim, improve and buy land at bargain prices. Most became cattle ranchers, the only logical choice in this unforgiving region. Little did they know the land they’d claimed was sitting atop the Hell Creek Formation, a 300-foot-thick bed of sandstone and mudstone that dates to a period between 66 million and 67.5 million years ago, the time just before dinosaurs went extinct. Stretching across the Dakotas and Montana (in Wyoming, it’s known as Lance), the formation—one of the richest fossil troves in the world—is the remnant of great rivers that once flowed eastward toward an inland sea.

Before his father died, and the homestead was divided among four descendant families, including Phipps and his two siblings, Phipps scraped by as a ranch hand on a neighboring ranch. He and his wife, Lisa, a teacher’s aide at the local school, lived in a cabin on the rancher’s property. One day in 1998, Phipps says, a man showed up and asked the landowner’s permission to hunt fossils. Given consent to roam the property for a weekend, the man returned Monday morning and showed Phipps a piece of triceratops frill—part of the shield-like structure that grew around the massive plant-eater’s head.

“He told me: ‘This piece is worth about $500,’” Phipps recalls. “And I was like, ‘The heck it is! You found that just walking around?’”

From that day on, whenever Phipps wasn’t doing ranch work, he was out looking for fossils. What he found he prepared in his basement workshop, or consigned to others to prepare, for sale at trade shows and to museums and private collectors. In 2003, he unearthed the head of the horned Stygimoloch—from the Greek and Hebrew, roughly, for “demon from the river Styx”—a bipedal dinosaur, about the size of a bighorn sheep, prized by collectors for its highly ornamented skull. Phipps sold the fossil for more than $100,000 to a private collector, who placed the specimen in a museum in Long Island, New York.

Then, one hot day in 2006, Phipps and some partners made the discovery of a lifetime—experts say it might well be one of the greatest fossil specimens ever unearthed. Or, more accurately, two specimens. Jutting out from a desiccated hillside were the remains of a 22-foot-long theropod and a 28-foot-long ceratopsian. Locked in mortal combat when they were instantly buried in sandstone, perhaps along a sandy riverbed, the incredibly well-preserved pair is forever captured in a moment in time from more than 66 million years ago. “There’s an entire skin envelope around both dinosaurs,” Phipps says. “They’re basically mummies. There could be soft tissue inside.” If true, the specimen offers the possibility that scientists might recover tissue cells or even ancient DNA.

The exact species of the Montana Dueling Dinosaurs, as the specimens have become known, are still in contention. The larger of the two appears to be a ceratopsian, from the family of beaked and bird-hipped plant-eaters beloved by children for their horned faces. The existence of additional horns on the animal’s faceplate, however, has led to some speculation that it may be a rare or new species. The smaller specimen appears to be either a juvenile Tyrannosaurus rex or a Nanotyrannus, a dwarf species, rarely documented, the very existence of which some scientists dispute.

Scott Sampson, a paleontologist and the president of Science World, a nonprofit education and research facility in Vancouver, is among the few academics, museum officials and commercial collectors who have viewed the specimen. “The Dueling Dinosaurs is one of the most remarkable fossil discoveries ever made,” he says. “It is the closest thing I have ever seen to large-scale fighting dinosaurs. If it is what we think it is, it’s ancient behavior caught in the fossil record. We’ve been digging for over 100 years in the Americas, and no one’s found a specimen quite like this one.”

And yet there is a chance the public will never see it.

**********

We may speculate romantically about how far into the past dinosaur fossils were collected by our hominin ancestors, but the study of dinosaurs is a relatively new science. Deep thinkers in ancient Greece and Rome recognized fossils as the remains of life-forms from earlier epochs. Leonardo da Vinci proposed that fossils of marine creatures like mollusks found in the Italian countryside must have been evidence of ancient seas that once covered the land. But for the most part, fossils were regarded as the remains of gods or devils. Many believed they had special powers of healing or destruction; others that they were left behind from Noah’s flood, a notion still held by creationists, who deny evolution.

Dinosaurs inhabited much of the earth, but their fossils are not easily found in most places. The western United States is a treasure trove due to a combination of factors: We live during a sweet spot in time when the rock layers laid down during the end of the Cretaceous Period have become exposed after eons of erosion, a process accentuated by the stark environment, lack of plant life and extreme weather conditions that continually reveal ever new layers of ancient rock. As layers of the earth’s surface erode, fossilized bones of dinosaurs, more solid than the sand and clay in which they are buried, peek through.

In the early 20th century, universities and museums frequently commissioned commercial bone diggers to excavate dinosaur fossils. Many of the oldest specimens on display in museums in the United States and Europe were uncovered and harvested by these “professional amateurs.” While federal land can only be prospected by accredited academics in possession of a permit, dinosaur bones found on private land are private property: Anybody can dig with the permission of the owner.

In 1990, a group of paleontologists digging on the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation, in South Dakota, unearthed an enormous and incredibly well-preserved T. rex. Later named “Sue,” it is to date the largest and most complete specimen ever found, with more than 90 percent of its bones recovered. Sue was auctioned in 1997 for $7.6 million to the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, the most ever paid for a dinosaur fossil.

The record sale was publicized around the world and kicked off a sort of dinosaur bone “gold rush.” Scores of prospectors descended on Hell Creek and other fossil beds in the West, drawing the ire of academics, who contend that fossils should be extracted according to scientific protocols, not ripped from the ground by profit-seeking amateurs. To scientists, every site contains much more than fossil trophies—the plant, pollen and mineral records, as well as the exact placement of the find, are critically important to understanding the history of our planet. Over the following decade, the mania for dinosaur bones was fueled by the popularity of movies like Jurassic Park, booming wealth in Asia, where fossils became ultra-chic for use in home décor, and the media’s attention to celebrity collectors like Leonardo DiCaprio and Nicolas Cage. At the height of the bone rush, there were perhaps hundreds of prospectors conducting digs across hundreds of thousands of square miles, ranging from the Dakotas to Texas.

One of them was Cowboy Phipps.

**********

It was a typical day in early June, clear with the mercury in the triple digits, when Phipps discovered the Dueling Dinosaurs.

He was prospecting with his cousin Chad O’Connor, 49, and a friend and fellow commercial bone digger named Mark Eatman, 45. O’Connor, strong and good-humored, is partially disabled by cerebral palsy. This was his first time hunting for dinosaur bones. He’d later say he accompanied his cousin on the expedition in the hope he’d “find something that could change my life.”

Eatman had been a full-time prospector for many years before falling demand and prices for fossils, along with a three-year stretch of bad luck, forced him to give up the game. “His wife told him it was time to get a real job,” Phipps says.

Eatman found work selling carpet in Billings. On occasion he’d join Phipps for an expedition, sometimes camping out for a few days at a time. Bone diggers across the spectrum—commercial, academic, amateur—would probably agree that the hunt is often as important as the find, an opportunity to get out into nature and to collaborate with like-minded people beneath the same ancient stars the dinosaurs stood under.

Phipps and his partners were checking out an area about 60 miles north of Phipps’ ranch. Because he was using “a small map of a big area,” Phipps says, he believed they were on land his brother was leasing, in the Judith River Formation, which predates Hell Creek by at least ten million years. Later, Phipps discovered they were actually prospecting about ten miles north of where he thought they were, in the area that Phipps, like most of the locals, calls Hell Crik. The land was part of a 25,000-acre ranch owned by Mary Ann and Lige Murray.

The men picked their way through the sunburnt environment, the ground a mix of eroded clay, shale and sand. The topography is riven with canyons, ravines and gullies, interrupted by striated buttes, hunkered beneath the cloudless sky like silent messengers from the past. In the time of the dinosaurs, the Hell Creek area was subtropical, with a warm and humid climate. The swampy lowlands were rich with flowering plants, palmettos and ferns. At higher elevations were forests of shrubs and a variety of broad-leaved trees and conifers.

About 66 million years ago, an asteroid collided with the earth, leading to the extinction of the dinosaurs and much of the earth’s fauna and paving the way for the evolution of mammals and modern plants. Today, Hell Creek is stark, hot and seemingly deserted. The crew made its way around low-growing cactuses, through prickly and fragrant sage, over tuffs of wild grasses. Phipps was riding a small, off-road motorcycle. The other two men were on foot.

Along the way they encountered an occasional set of sun-bleached bones, late of a grazing cow or other denizen: prairie dog, mule deer, antelope, coyote.

At about 11 a.m. Eatman spotted what looked like a piece of massive bone sticking out of a sandstone bank. Phipps approached the hillside for closer inspection. Right away, he says, “We knew we had a pelvis, possibly of a ceratopsian. And we knew we had the femur articulated into the pelvis—we could see the head of the femur.” What they didn’t know was whether any more of the creature was buried beneath the sand, or whether the rest of the dinosaur had already been washed away from erosion.

Phipps marked the spot carefully in his mind’s eye, and then he and the party headed home. The answers to these mysteries would have to wait for another time.

“I had 260 acres of hay to cut,” he says.

Prehistoric Beasts of the Badlands

From remarkable T. rex skeletons to a 66-million-year-old mummy, here are 10 celebrated fossils unearthed at Hell Creek (Map credit: Guilbert Gates; Research credit: Ginny Mohler)

**********

Later that summer, after the hay was mowed, rolled and put up—feed for his cattle over the long winter—Phipps returned to the secret location, this time in the company of Lige Murray, the landowner.

Now Phipps found pieces of ceratops frill that had already weathered out of the bank. He could also see a line of vertebrae leading toward a skull. It seemed likely the dinosaur’s back end was buried in the hill—meaning there was a good chance it was still intact.

Murray gave his approval, and Phipps began the painstaking process of excavating, starting with a brush and a penknife. Meanwhile, business partners were gathered; contracts were signed. A $150,000 loan was arranged. A road to the site was constructed.

Most of the arduous work of extraction was done by Phipps and O’Connor. “He doesn’t get around very good, but he’s got a great sense of humor,” Phipps says of his cousin, who helped ease the burden of their long, hot days. Eatman came up on weekends to help, as did a small cast of confidants and colleagues, who lent elbow grease and expertise. The find was kept secret throughout the entire process. “I didn’t even tell my family until just before we finished the excavation,” Phipps says.

After two weeks, Phipps had established a perimeter around the ceratopsian from head to tail. “We had basically all the bones to his body mapped out at that point,” he says. One day he was sitting in the cab of a backhoe he’d borrowed from his uncle, which he was using to remove the soil behind and around the specimen to prepare the area for the fossil’s removal.

“I went to dump my bucket—as usual I was watching very carefully,” Phipps recalls. “Suddenly I see these bone chips. The bones were easy to tell from the light-colored sand because they were dark in color, like dark chocolate.”

Phipps clambered down off the backhoe and began to sift the contents of the bucket by hand. That’s when he saw it: “There was a claw,” he says. “And it was a carnivore claw. It’s not any bone that goes with a ceratopsian.”

Phipps smiles at the memory. “Man, my hat went in the air,” he recalls. “And then I had to sit down and think, like, What’s going on? Here is this meat-eater in with this plant-eater, and obviously they weren’t friends. What are the odds of another dinosaur being there?”

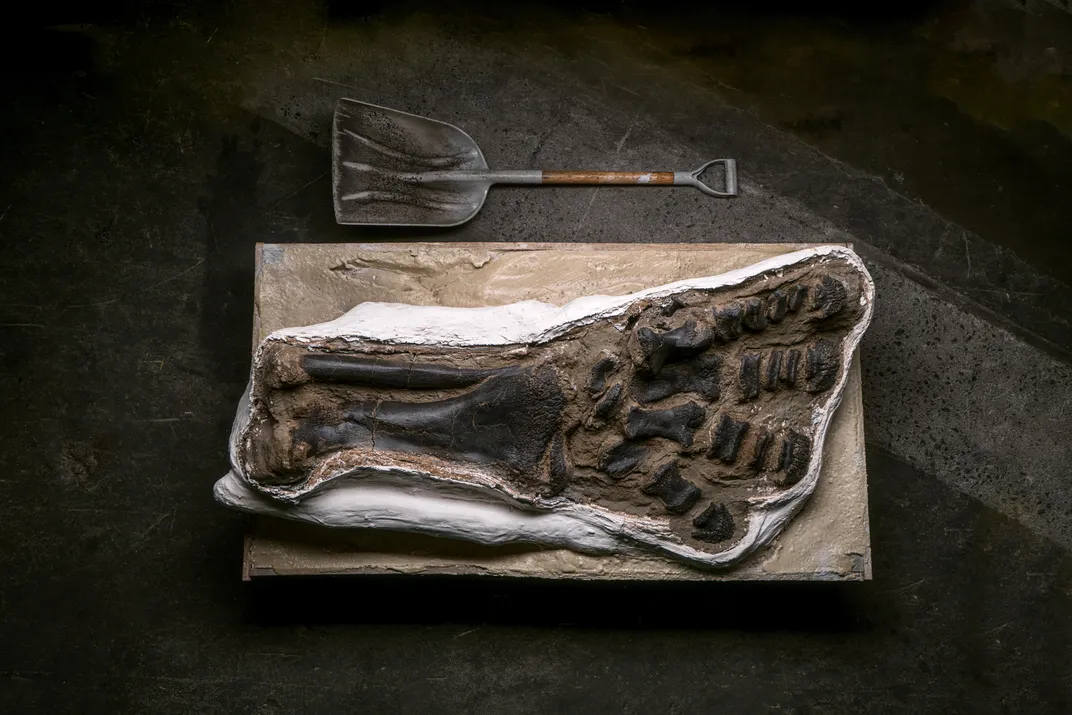

It took Phipps and his partners three months to extract the specimens from the remote site. The sinewy Phipps lost 15 pounds in the process. Railroad ties were inserted beneath the Dueling Dinosaurs to preserve their position and integrity. Plaster jackets were placed around the exposed bone, a standard procedure among paleontologists. In the end there were four large sections and several smaller ones—all together they weighed nearly 20 tons. The section of earth containing the theropod alone was the size of a small car, weighing some 12,000 pounds.

Phipps enlisted the help of friends at CK Preparations, run by a preparer named Chris Morrow and the paleoartist Katie Busch. The multi-ton blocks were transported to a facility in northeastern Montana, where Phipps and his partners carefully removed the jackets. Next the specimens were “cleaned down to the outline of the bones, so you could see everything that was there, how each animal is arranged,” Phipps says. About 30 percent of the fossils were exposed, the bones shiny and dark.

In situ, Phipps explains, using a model he holds in his lap, the skeletons overlapped, with the tail of the theropod, which was about the size of a polar bear, resting beneath the back foot of the elephant-size ceratopsian. Both dinosaurs, buried in some 17 feet of sand, are fully articulated, meaning their skeletons are intact from nose to tail.

Phipps speculates that on the day in question, scores of millions of years ago, one or more Nanotyrannuses attacked the ceratopsian. A number of theropod teeth were found around the site, and at least two were embedded in what were the ceratopsian’s fleshy areas, one in the throat and one near the pelvis. Scientists believe that theropods shed teeth and quickly regrew them, like sharks. In this case, Phipps says, some of the theropod’s teeth are broken in half, indicating a violent fight.

A pitched battle ensued. “The ceratopsian is almost ready to die,” Phipps says, picking up the narration and growing animated. “He’s hot, he’s tired, he’s whipped, he’s bleeding from all the bite marks in him. Just as the ceratopsian is about to tip over, he staggers around and steps on the nano’s tail. Well that hurts, right? So the nano bites the ceratopsian’s leg. And what’s the ceratopsian gonna do? Instinctively he kicks the nano in the face. The nano’s skull is actually cracked. When the ceratopsian caved in the side of the nano’s head, the force slammed him into a loose sandbank—and the wall of sand came down,” burying them both instantly.

“There’s so much science in these dinosaurs!” Phipps exclaims, a rare show of emotion from a guy who likes to wear his black cowboy hat low on his brow. “There may be last meals, there may be eggs, there may be babies—we don’t know.”

**********

Well aware he’d found something special, Phipps set out to alert the world.

There was only one problem: Nobody would listen. “We called every major American museum and told them what we had,” Phipps says. “But I was a nobody. A lot of them probably thought, Yeah, right. This guy is crazy. Nobody sent anyone to verify what we’d found.”

In time, though, word got out. Sampson, the Canadian paleontologist, then with the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, spent an hour with a group from the museum examining the fossils in a Quonset hut in eastern Montana. “We were blown away,” Sampson says. “It’s an amazing specimen.”

Several other experts who’ve seen the Dueling Dinosaurs have come to the same conclusion. “It’s exquisite,” says Kirk Johnson, director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. “It’s one of the more beautiful fossils found in North America, ever.” Tyler Lyson, a curator at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, calls it a “spectacular discovery. Any museum would love to have it.”

But not everyone agrees. “As far as I’m concerned, those specimens are scientifically useless,” says Jack Horner, the pioneering and world-famous paleontologist who was the inspiration for the dinosaur expert played by Sam Neill in Jurassic Park. “Every single specimen collected by a commercial collector is useless, because they do not come with any of the data” that academically trained paleontologists are careful to collect, Horner says.

As time dragged on, Phipps tried everything he could think of to find a buyer for the Dueling Dinosaurs. “There were a few museums that were interested,” he says. “We got close with one. I was negotiating with the director, and we actually came to an agreement on a price at one point. And then—nothing happened. They didn’t get back to us. I don’t know more than that.”

**********

In 2013, after seven years in the lab of CK Preparations, the Dueling Dinosaurs were brought to auction at Bonhams, in New York City. It was valued by appraisers as high as $9 million, according to Phipps.

To transport the specimens from Montana, custom crates had to be built for each section. A special semi-truck with an air-ride suspension was hired. Phipps and his party flew to New York.

Bonhams displayed the fossils in a large atrium room at its facility on Madison Avenue. The crowd at the event was a mix of “professorial baby boomers, wily prospectors, impeccably dressed collectors,” according to an account of the event published by the website Gizmodo. Phipps, the website reported, “wore a rancher’s vest, neckerchief and black cowboy hat.”

The bidding on the Dueling Dinosaurs lasted just 81 seconds. The only offer was $5.5 million, which failed to meet the reserve. (Although the reserve price was not publicly announced, Phipps says it was closer to the appraised figure of around $9 million.) “I just felt that they were worth probably twice what we were offered,” Phipps says. “We were expecting better, and we weren’t willing to take that.”

Perhaps reflecting the falling market for fossils, a number of other items failed to sell that day, including a triceratops skeleton, valued between $700,000 and $900,000, and a Tyrannosaurus rex valued at up to $2.2 million.

Three years later, sitting in his office, there is regret in his voice. “The reason they went to auction was sort of out of frustration on my part. And then it was over before it started. It was disappointing that we couldn’t make a sale, but I guess I was half expecting it. My attitude is always the same: You don’t count your chickens before they hatch.”

Since then, the Dueling Dinosaurs have been housed in a storage facility at an undisclosed location in New York. They remain unstudied more than a decade after they were exhumed. In the meantime, Phipps has been regarded by some, however undeservedly, as a privateer devoted more to money than to science.

“I’ve never had any money, so money’s never been all that important to me,” he says. “But I’m not gonna just give them away. There were people that said I should just donate them. Well, no. I’ve got partners. I’ve put too much into the project. I was out there trying to make a living. It’s just like them academics that come out every summer between classes to look for fossils—they’re trying to make a living, too.”

Johnson, of the Smithsonian, says there is tremendous value in the Dueling Dinosaurs, despite some of the criticisms leveled against how the specimens were excavated. “There’s scientific value, there’s display value, there’s the novelty of the two of the dinosaurs being adjacent,” he says. But, he adds, “the price tag is sort of out of reach of most museums, unless somebody comes along who wants to buy it and donate it. And that hasn’t happened yet.” Johnson says he viewed the Dueling Dinosaurs in the company of a wealthy museum supporter whom he invited, hoping the man might take an interest in the fossil. It turned out the donor had already seen it—with an official from another museum. “There really aren’t that many buyers for something like this.”

The sale of Sue, the T. rex, for more than $7 million, was a “high-water mark” for fossils, Johnson says, reflecting unprecedented donations by corporate sponsors like McDonald’s and Disney. “Sue changed everything, because ranchers went kind of nuts when they realized that dinosaurs weren’t just old bones, they were a source of money—and that screwed everything up.”

Tyler Lyson, of the Denver Museum, says it would unquestionably be “a shame if it ultimately doesn’t end up in a museum.” A Yale-trained paleontologist who grew up about three hours southeast of Phipps, along the Montana-North Dakota border, Lyson got his start hunting fossils on ranch land homesteaded by his mother’s family. Improbably, through a series of scholarships, his childhood hobby became his life’s work.

“There’s only a certain percentage of people on the planet who are interested in fossils to begin with,” Lyson says. “We all share that common bond, even though we might be interested for different reasons.”

**********

At five o’clock, Phipps’ wife rings the dinner bell. Phipps hoists himself out of the chair and gingerly climbs the stairs. Three months ago, he and his 12-year-old son were cutting a calf from the herd when Phipps’ horse slipped and rolled over on top of him. Phipps broke his leg in several places; his foot was turned the wrong way. His son, thinking he was dead, began to administer CPR. Last week the screws were removed from the leg; it looks like he will recover full use. Of course, during his convalescence, an entire prospecting season was lost, along with any hope of any income from fossils—revenue that over the years has accounted for two-thirds of his annual income, he says.

Besides her duties at the nearby one-room schoolhouse, Lisa Phipps has published two children’s books. We are joined at the table by the couple’s two boys, the younger of whom is 10. (Their eldest, a daughter, is in nursing school.) We eat a convivial supper of shredded chicken, potatoes and squash. The windows frame the rugged beauty of the surrounding countryside. The early evening sunlight creates an intimate glow. Beside my plate, in two little plastic bags, are a pair of triceratops teeth that Phipps has given me as a remembrance of my visit.

“The academics think what I’m doing is horrid,” Phipps is saying. “They think I’m destroying fossils and selling them to the highest bidder. But that’s not true,” he says, anger rising in his voice. “I love fossils as much as they do. Granted, I’m self-taught. I’m just a cowpoke, I don’t know everything. But I’ve had several paleontologists, even ones who don’t exactly condone what I do, tell me I did a good job getting the fossils out. Maybe I didn’t do the totally detailed scientific work like they do, but I don’t have 30 college students under me working for nothing. When we found the Dueling Dinosaurs, I thought the academics would be big enough to bridge the gap. I figured they’d say, ‘OK, this is a once in a lifetime find.’”

Someday, Phipps hopes, the divide with the academic community will be bridged and whatever valuable scientific data the Dueling Dinosaurs retain will be reaped. “The dinosaurs have been removed,” he says. “If we left them in the hill, the weather would have destroyed them in the last eight or ten years since we dug them out. We did the best we could with what we had at our disposal. You gotta make up your own mind if what I do is wrong or not. But to me, it’s not.”

After my visit, not long before this article went to press, Phipps told me that there have been renewed overtures from a museum interested in buying the Dueling Dinosaurs. “There are some things happening, but I’m not at liberty to discuss it,” he said. But he did suggest that sufficient funds haven’t yet been raised. “It’s like anything in business, I guess. You want a fair price. I’m gonna wait and see what happens. I’m not in any hurry.”

In the meantime, Phipps says, “I’ve paid back my debts, and I’m trying to build the ranch up a little more, and to get more cattle. I’m leasing more ground now, too. I’m trying to focus on that, because fossils aren’t a guarantee, you know?”

Related Reads

Hell Creek, Montana: America's Key to the Prehistoric Past