The Quest to Grow the First Great American Wine Grape

Genetics might be the key to creating vineyards that both resist disease and don’t taste like skunk

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e1/8f/e18f3dde-5dec-4ea0-8207-8398d8b8f625/unknown-1.jpeg)

This article is adapted from an excerpt of the upcoming book, Taste the Past: the Science of Flavor & the Search for the Origins of Wine.

There’s no nice way to put it: American grapes make bad wine. At least, that’s their reputation. For decades oenophiles have turned up their noses at the idea of native American grapes, with the industry bible Oxford Companion to Wine describing their flavors as being akin to “animal fur and candied fruits.” And so the Napa Valley grew famous with its plantings of Chardonnay, Merlot, Sauvignon, Cabernet or Pinot—the so-called “noble” French grapes—while Concord grapes were deemed only fit for jelly and juice.

But American wine grapes are poised for an epic rebrand. Using DNA analysis and other high-tech tools, a group of scientists in Minnesota, California, New York and other states have taken a harder look at indigenous American grapes and found long-hidden qualities that could redeem them even to the most snobbish of wine-sippers. Their goal: to produce a drink whose taste and quality can compete with the most coveted French and Italian vintages.

“We have grapes that taste like pineapple, strawberry, black pepper. I think the resources are only limited by the amount of time we spend exploring them,” says Matthew Clark, an assistant professor of grape breeding and enology at the University of Minnesota. “We’re really trying to develop wine products that are more in the European style, but utilize the resources of the North American germ plasm.”

Clark is part of VitisGen, a project that aims to do for wine what the Human Genome Project did for humans. That is: use the vast power and rapidly declining cost of DNA research to pinpoint the precise chromosomal locations in American grapes that drive flavors, aromas, grape size and other important attributes. The U.S. Department of Agriculture began funding VitisGen in 2011, and then VitisGen2 in 2017. The project now includes scientists from Cornell University, the University of California at Davis, the University of Minnesota and other universities, as well as industry giant E&J Gallo.

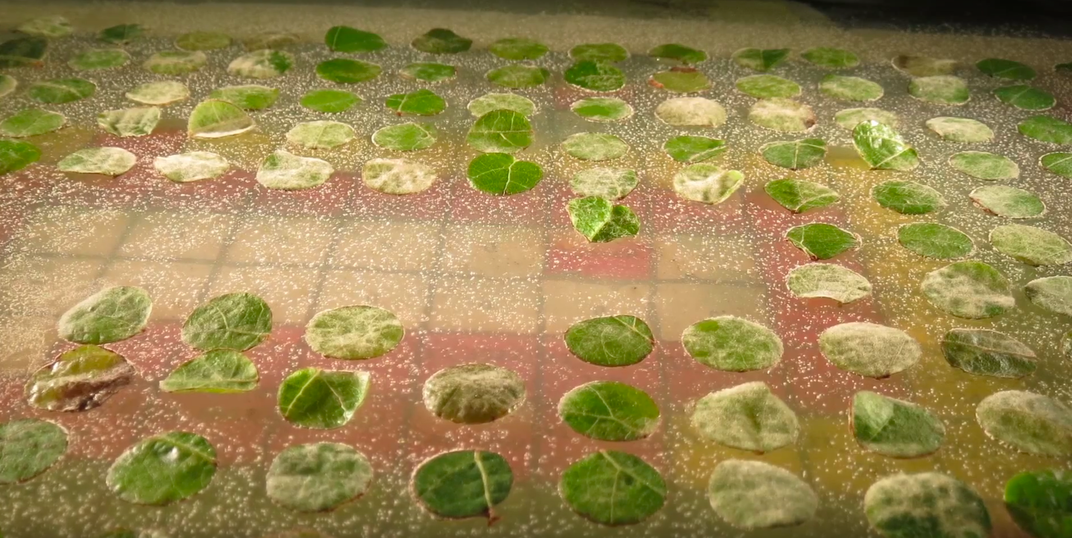

The new research has uncovered another valuable trait as well: a reservoir of natural pest and disease resistance. Like strawberries, grapes are particularly vulnerable to pests and disease, which explains why more than 260 million pounds of pesticides were applied to vineyards between 2007 and 2016 in California alone, according to official state records.

Downy mildew is one of the leading global problems. So is Pierce’s disease, which causes entire vineyards to wither and die and is transmitted by small winged insects called sharpshooters. Much of the vineyard treatments involve sulfur and copper—relatively low-risk chemicals—but even those traditional sprays can cause problems. Breeding grapes with their own resistance to these threats could be a life saver for vineyards across the country.

Clark says the new CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology could speed up the creation of new varieties by precisely deleting the DNA that drives unwanted attributes. "It’s a tool that plant breeders are certainly using in a number of crops. Some of the questions that come to mind, and I don't know if these are warranted or not, but what do you put on a bottle? What would the label say when you have [a] wine that has now been, for lack of a better word, modified with CRISPR?” Clark wonders.

It may even be possible to breed those nasty “animal fur” flavors out of native American grapes. “We’re doing work right now to identify some of the off aromas and flavors, and we’re making great strides,” says Clark. “Ultimately our goal is to have a DNA test that we can use to screen a seedling years before it produces its first fruit as part of the breeding program, to determine if it has that negative trait or not.”

Yet another challenge awaits this theoretical improved American wine. Compelling science and environmental benefits are all well and good, but will picky wine lovers accept these unfamiliar grapes? One answer came in 2015, when The New York Times listed the top 10 wines of the year. “A few years ago, I never imagined I would fall in love with a Vermont wine,” critic Eric Asimov wrote of Deidre Heekin and Caleb Barber’s La Garagista vineyard. “[But the] wines are so soulful that they demanded my attention. I was especially taken with the floral, spicy, lively 2013 Damejeanne.”

It was as if a Kansas restaurant had won Times praise for best sushi.

The wines he loved used Marquette red and La Crescent white grapes, both created at the University of Minnesota (UM). UM varieties are now grown in numerous states, and in Canada. “The wines we produce, that niche itself, they offer some unique flavor profiles. It’s an opportunity for someone who’s interested in locally produced products,” Clark said, adding that large producers such as Gallo may be able to use such grapes for blended wines that don’t specify a particular variety.

The Seeds

The Minnesota program began in the mid-1980s, but moved very slowly at first. “It really took nearly 20 years to get Frontenac, our first variety, out [into vineyards],” Clark said. Frontenac was a hybrid: 50 percent from a wild Vitis riparia American vine, and 50 percent from Vitis vinifera, the European grapevine. Other new cultivars come from the American native grapes V. labrusca or V. rupestris.

In the past only one out of 10,000 Minnesota grape seedlings made it to the stage of being grown in vineyards. Many have one desirable trait but lack others, such as berry size or productivity. “So it really is a numbers game,” Clark said in a phone call. Now VitisGen is speeding up the process.

The American grapes clearly have potential, but one expert pointed to an obstacle. For U.S. consumers, grape variety and wine preference are strongly linked, notes Geoff Kruth, a Master Sommelier and the president of GuildSomm, an international nonprofit based in California. “It takes quite a bit of time and exposure for new grapes to catch on with the drinking public,” Kruth wrote in an email. “If the quality is there, unknown varieties with good yields can always find a home in blends or niche bottlings. But you wouldn't want to be in a position to have to sell large quantities of any wine without a familiar grape variety or brand name blend.”

Clark is optimistic, given the strong interest in regional foods, craft brewing and small distilleries in recent years. “Maybe we'll swing back to where we were before the '70s, where people bought red wine and white wine, or bought by region. And they weren't looking for Chardonnay, or Merlot or Pinot on the label.” Maybe next time, they’ll be looking for Vermont.

Viticultural Apartheid?

To understand the challenge of creating a truly American wine grape, you have to understand that viticulture has become a monoculture. French grapes dominate the marketplace, especially in America.

I asked geneticist Sean Myles if there was any justification for planting only the famous varieties. He’s at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, and was the lead author on a widely cited 2011 grape genome paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. DNA analysis showed that humans have been breeding and mixing grape varieties for at least 8,000 years—when organized winemaking began in the Caucasus Mountain region. That’s thousands of years before the French started making wine.

Myles reeled off a botanical sermon about rampant viticultural apartheid. “If applied to any other category you’d say this is just plain old racism. A little bit of wild ancestry? Ah, you’re still a hybrid. You’re inferior to the noble European grapes,” Myles said of the prejudice against American grape DNA.

One grape scientist who isn’t involved with the VitisGen research said the shift towards global grape monoculture began in the late 1800s. Before that time many countries and regions grew hundreds and hundreds of local varieties. Then in the 1860s a tiny, aphid-like pest called Phylloxera began destroying vineyards throughout Europe. Two things happened during replanting.

“First, they had to choose which variety to use, and in many cases—not only in France, but also in Switzerland, Italy, and Germany, and everywhere—they had a tendency to forget the old (native) grandfather varieties,” says Jose Vouillamoz, a Swiss wine scientist and co-author of the acclaimed reference book Wine Grapes. “And they chose to plant varieties that were easier to cultivate, and especially that would produce more. So that’s why in many regions some of the ancient, traditional varieties have been almost abandoned, or sometimes have disappeared.”

The solution to Phylloxera was grafting European vines onto American rootstock, which had natural resistance.

In recent decades the global shift towards monoculture has accelerated, even as some vineyards try to preserve old local varieties. A study in the Journal of Wine Economics found that between 1990 and 2010, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot more than doubled their share in the world’s vineyards. By 2010 French grape varieties comprised 67 percent of vineyard acreage in New World countries, up from 53 percent just 10 years before.

Inbred Nobility

A final irony is that oenophiles are in some ways loving their famous French grapes to death—or more precisely, preventing them from loving at all. In an obsessive quest to keep classic wine flavors consistent, vineyards stopped natural crossbreeding. Instead, new vines are created not from seeds but by cutting pieces of existing vines and grafting them to rootstock. (The grapes self-pollinate, too, so aside from mutations the DNA doesn’t change.) In other words, the famous grapes stopped evolving—but insects and diseases didn’t. For example, Pinot Noir may date to the Roman era.

A VitisGen summary notes that modern grape production is expensive and requires large quantities of chemicals, “largely due to the widespread planting of unimproved cultivars, developed 150—2000 years ago, that are highly susceptible to biotic and abiotic stresses.”

Myles elaborated, with a grim prediction. “That is going to be the potential demise of the entire international wine industry as we know it today. The industry is losing the arms race to the pathogens that continually evolve and attack the grapevines. It’s really only a matter of time. If we just keep using the same genetic material, we’re doomed,” he said.

That might seem unlikely, except that botanists can cite examples where excessive crop monoculture led to disaster. By the early 1800s most people in Ireland were planting just one potato variety, propagating it from shoots. That wasn’t a problem until the rot disease Phytophthora infestans showed up in the 1840s, destroying entire harvests and leading to massive starvation. The Gros Michel banana dominated markets until the 1950s, when a fungus destroyed many plantations. It was replaced by the supposedly immune Cavendish, which now occupies about 90 percent of the world market. But the old Gros Michel fungus kept on evolving—and now it can attack Cavendish, too.

It’s a Catch-22 for the industry: keep using the same grapes wine-lovers expect, even as they grow weaker genetically, or risk introducing unfamiliar new varieties.

Tasting the Past: The Science of Flavor and the Search for the Origins of Wine

In this viticultural detective story wine geeks and history lovers alike will discover new tastes and flavors to savor.

Psychology, Wine and Climate

For centuries winemakers had no precise way to separate the good characteristics in native grapes from the obviously bad ones. Now they do. Andy Walker, a viticulture expert at the University of California at Davis who is also part of the VitisGen project, says the continued aversion to American varieties is purely psychological.

“And in fact”—given the social pressures to reduce chemical use and the way climate change is already impacting wine growing regions—"we’ll have to get over it,” he says.

Vouillamoz agrees that climate change will ultimately force vineyards to make tough decisions. To make the point, at one wine conference he faked a bottle of Domaine Romanée-Conti—one of the most renowned and expensive wines in the world. “And I put on the label, the vintage 2214. And I was asking the audience what do you think will be in this bottle, in 200 years from now. Will there still be Pinot Noir, as it is today, or something else?” he says.

Vouillamoz says Pinot Noir grapes in Burgundy are already out of the optimal window of cultivation because of increasing heat, yet Romanée-Conti’s legendary owners would turn in their graves if future generations plant some other variety. It would be like planting date palms to replace the Washington, D.C. cherry trees.

“So if you want to keep Pinot you can do adjustments, but at some point you will need some more help,” Vouillamoz says. That could mean tweaking Pinot with heat-resistant genes from some obscure vine.

Scores of smaller vineyards are now using native grape hybrids in cool climate areas across North America. In 2014 Ducort vineyards in Bordeaux planted new vines that contain disease-resistant genes, and German vineyards have done similar plantings.

But the general public might be confused by such grapes. Scientists overwhelmingly agree that GMO crops are safe to eat, but consumer resistance is a reality. One newspaper mistakenly used the term “Frankengrapes” to describe Walker’s research. That word was originally used to describe an early GMO tomato variety that contained a flounder gene. The headline was eventually changed, and Walker said the wine writer didn’t aim to denigrate his work. Yet the risk of exaggeration was there.

Technically, the VitisGen scientists are using genomics and other tools just to identify various genes – not to insert other animal or plant species DNA beyond grapes. Clark says it’s essentially a greatly speeded up version of old-fashioned breeding. Walker agrees. “There’s no reason to use genetic modification unless you don’t have the genes at hand. And within Vitis we have everything we need,” he says of the native grape varieties.

Using just a handful of grapes doesn’t even make sense from a purely sensory point of view, Walker adds. “We’re still caught in that trap of saying, ‘well, there are only 10 good varieties in the whole world, and that’s it.’ Anyone who’s drunk wine around the world realizes this is a complete fallacy,” he says. “There are wonderful wines to be made everywhere from a huge number of varieties. But it’s a marketing scam that we ended up with 10 varieties that are [supposedly] destined to be the best in the world.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.