The Real Cougars of Malibu Have Lives Full of Murder, Bad Sex and Poison

But a simple bridge over the freeway could help save the charismatic big cats

:focal(1248x809:1249x810)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/73/59/73596cb1-de55-4ae1-b912-e8c65b4781fc/13391606225_4270c594f6_k.jpg)

Murderous family feuds, car accidents, accidental poisoning—it’s just another day in sunny California for the mountain lions of Malibu.

On a February morning in the rugged mountains west of Los Angeles, just around the creek from where they filmed the TV show “M.A.S.H.”, biologist Jeff Sikich is pointing his antenna toward a glade of chaparral between two craggy outcrops. He can’t see the mountain lion kittens that his sensors suggest are hunkered down over a fresh deer kill, but they’re almost certainly staring right at him from only a football field away.

Though definitely near her three-month-old cubs, the mom’s whereabouts remain a mystery, which is not an uncommon situation for Sikich. The world-renowned big cat expert and “capture specialist” has been tracking mountain lions in the Santa Monica Mountains for the National Park Service since 2002, and he has only seen them in the wild a handful of times.

“I never see them, but they know we are here,” says Sikich, who has also tracked pumas in Peru, tigers in Sumatra and leopards in South Africa. “Mountain lions are elusive creatures. They are extremely difficult to study.”

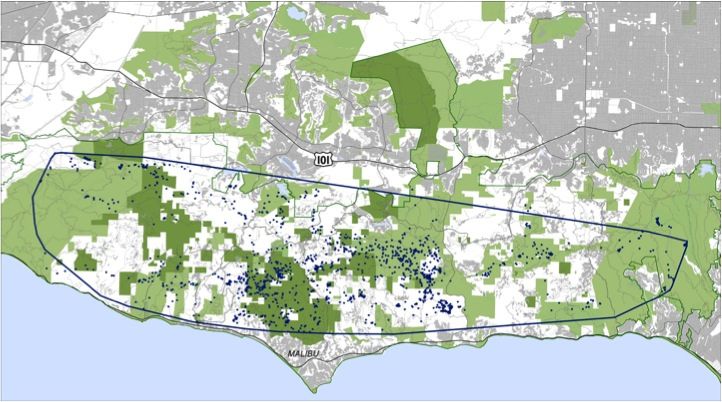

These mountain lions should consider making things a bit easier for Sikich and his colleagues—their research may be the big cats’ only hope for long-term survival. The roughly 300-square-mile mountain range the lions call home is hemmed in by two of the world’s busiest freeways, Route 101 and I-405, as well as the suburbia of Los Angeles to the south and east, the Pacific shoreline to the west and the agricultural sprawl of the Oxnard plain to the north. The range itself is dotted with ranch homes, crisscrossed by busy highways such as the famed Mulholland Drive and visited by millions of hikers, bikers and equestrians a year.

These mostly manmade boundaries block any new lions from coming into the Santa Monicas, while thwarting the constant attempts of resident young males to leave, according to a landmark paper released August 14 in the journal Current Biology.

The study’s most dramatic findings provide conclusive evidence of inbreeding and a shocking leading cause of death: vicious cat-on-cat killings. Most of the deceased young males who haven’t been run over by cars have been victims of the one to two adult males that rule the entire range, which occasionally means the youngsters are killed by their own fathers. Sikich’s work locating the bodies has revealed that the death strikes usually consist of one bite to the top of the skull.

Further complicating the conundrum, the study is the first to document how poison aimed at rats is proving lethal to mountain lions. “It is a soap opera when you get into the lion drama,” Sikich says. “The whole thing is unusual.”

And the most visible success story chronicled by the paper isn’t really a success story at all. The so-called “Hollywood lion” managed to make it across the two main freeways to Griffith Park, but that’s a dead-end route with no females in sight.

Despite being the western hemisphere’s widest ranging terrestrial mammal, relatively little is known about mountain lion behavior, even as humans steadily impede on their natural habitat. Until Sikich and Riley started their study in 2002, no one knew whether mountain lions even lived in the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreational Area, a 154,000-acre region considered America’s largest urban park. The National Park Service only owns 15 percent, with about half in private ownership, a quarter owned by California State Parks and the rest a smorgasbord of preserved open space and other land uses.

After following nearly three dozen lions over the years, the scientists believe that at any given time the range is home to about 10 to 15 independent lions, including usually two adult males, a handful of adult females and subadults of both sexes, but not counting any kittens. They know that the dominant males tend to use the entire range at some point in their lives, and that the subadult males prefer to stick to the fringes of the area, essentially hiding from the alpha cats. But secrets persist: In January, a kitten was killed while crossing Kanan Dume Road in Malibu, and it apparently came from a female adult that was unknown to the researchers.

Such information comes via various radio collars, from the high-tech GPS variety to low-tech but often more reliable VHF emitters. To outfit the big cats, Sikich mostly uses foot snares, which he finds the least traumatic option. “It’s our privilege to work with these animals, so it’s our responsibility to make sure it’s safe and ethical,” he says. Still, the snares can be a challenge: “We’re trying to get an animal that roams 300 miles to step in an area the size of a dinner plate.” He uses catnip oil, skunk essence and other tricks of the trade to lure the lions. In a pinch, he will employ cages or hounds as well.

The resulting 60,000-plus GPS data points offer a wealth of insight into the Malibu lions’ behavior, including the immediately obvious fact that they aren’t really interested in engaging with humanity. The big cats stick to the range’s wilderness areas 98 percent of the time, and there hasn’t been a single incident of these lions acting aggressively toward people.

“Even in the urban environment, they’re behaving like lions do in more natural areas,” Sikich says, noting that the cats even steer clear of golf courses, apparently realizing that they are developed areas. That’s excellent news for the 35 million annual visitors who flock to this popular park, which boasts more than 500 miles of trails— though the bulk of visitors stick to the Malibu beaches.

Younger lions exploring the edges of the range do occasionally stray into the urban landscape. One made it to 2nd Street and Wilshire in the city of Santa Monica in May 2012, before being shot and killed by police when a tranquilizer dart proved ineffective. The new study shows that such incidents are anomalies. And based on analysis of more than 450 cougar kills—95 percent of which were mule deer, with some coyote, raccoon, badger and other critters tossed in—the Malibu lions don’t appear to be preying on pets, as has been reported in other American urban-wilderness areas.

Mountain lions will prey on livestock, so the National Park Service is working with landowners and encouraging them to get guard dogs, among other strategies to keep the lions away. But the region isn’t home to much real ranching anymore, so there isn’t a lot of public uproar against efforts to protect a predator that humans once hunted as a nuisance. The Hollywood lion—which Sikich collared in March 2012—is even an icon of sorts, repeatedly snagging international headlines.

The most recent news, however, was that the Hollywood lion was suffering from the skin disease mange, triggered by ingesting rat poison, specifically the anticoagulants diphacinone and chlorophacinone that are used in many of the bait traps commonly seen around residential and commercial developments. Most likely, the cat preyed on something that had eaten poisoned rats—two previous lions died after eating coyotes that had ingested rat poison. “We know it’s moving up the food chain,” Sikich says, adding that he hopes local governments will enact bans on certain poisons to prevent future cougar deaths.

Genetically, the situation is a slow-moving disaster. “Our lions are pretty much trapped in here, which is not good,” Sikich says. “Eventually inbreeding will lead to low sperm counts and no more reproduction.” Known to scientists as Puma concolor, mountain lions are also called pumas, panthers and cougars. The fear is that the Santa Monica mountain lions will face the same predicament that their Florida panther cousins did in the 1980s, when inbreeding among the 25 remaining individuals led to kinked tails, whorled fur and holes in hearts. Conservationists introduced mountain lions from Texas into Florida in 1995 to diversify the gene pool and help save the panther population.

In a similar fashion, the new study presents a possible silver lining for the Santa Monica lions, although it may take a bit of gold to turn it into reality. Aside from the Hollywood lion, only one other newcomer has made it across the 101 since 2002. That male entered a part of the range that did have female lions and was able to breed. Based on the results, it seems that a tiny bit of genetic diversity goes a long way.

That bolsters the case for a wildlife corridor between the mountain range and the Simi Hills to the east; Sikich and his team say it would provide a critical connection to other lion populations. The project would cost millions of dollars and plenty of political capital, but it could ensure that these lions last into the future.

“We’ve spent millions and millions of dollars to preserve land in the Santa Monica Mountains,” says the National Park Service’s Seth Riley, the lead author of the study. “Is that all going to go to waste, at least from a mountain lion’s perspective, if we don’t solve the connectivity problem?”

The National Park Service isn’t allowed to lobby, but it can present evidence to support certain positions. “We’re allowed to establish a need,” said the service’s regional spokesperson Kate Kuykendall. “We think that’s what the study and research has established: the need for a wildlife corridor.”

The team says their paper offers some of the first concrete data supporting an already proposed overpass at Liberty Canyon. Here, a wildlife corridor could connect the isolated mountain lions to groups as far away as the expansive Los Padres National Forest, which spreads from northern Los Angeles County up to Big Sur. Such a project could become a proud symbol of how wildlife can survive in one of the world’s busiest, most populous cities, but so far it has been stalled by lack of funding and political support.

Four years ago, the cost of a 13-by-13-foot square tunnel under the freeway was estimated to be about $10 million, Riley noted as he stood looking out over Liberty Canyon, watching thousands of cars whiz by on the 101. That cost has probably risen since then, so he recently embarked on a study, paid for by the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, to analyze current costs as well as the possibility of the overpass, which would also benefit the bobcats, coyotes, deer and other creatures that thrive in the area.

“You don’t need that many successful genetic migration events to make a big difference, but you do need some,” Riley says. He cites breeding pattern research by geneticists at UCLA and UC-Davis and another recent paper that suggested one migrant per generation might be enough.

Unlike many people in his position, Riley, who started his career tracking raccoons in Washington, D.C., is not one of those scientists who will say that top predators must be saved to protect the whole ecosystem, because he truly doesn’t know what would happen if one day the mountain lions were gone. “We don’t really know all of their roles in the ecosystem,” he says. “But that’s not an experiment we want to conduct.”

Instead, he takes a much more ideological view of his role in saving the species. “My job is to protect the resources in these parks for future generations,” he says on the drive back to his office on the 101. “People care about open spaces, and they care about the wild creatures in them. If the day comes when we lose the last mountain lion in the Santa Monica Mountains, it will be a sad day.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/79/d179c7f5-dc53-4fac-af99-9f47b23dd6f7/8970178869_01c1fe0f40_k.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6d/b6/6db6aba5-b30c-4036-b81b-7295067ae322/8970211263_3a67b52989_k.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bf/34/bf341c5f-151b-4025-bc0a-01f87f2c5c84/13391737063_cb7b1b911c_k.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5e/64/5e645bf1-a1b5-43a7-88a6-7873611eacfe/8970174347_802b172da1_k.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/48/08/48086011-07ab-4871-8099-d35a27ca1275/8971368960_2afada6f45_k.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ac/43/ac43c24f-1cbc-4f1b-a405-42e4b04f9edf/dsc_0005jpg.jpeg)