Can Returning Farmland to the Wild Help Bumblebees in Crisis?

Even if only a small percentage of current farmland became wild meadows, it could bring populations back to previous levels

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9c/2e/9c2e5e11-ff74-4f33-a234-06734e66fb41/apr2015_d03_phenom.jpg)

When I first saw the field on a damp October day, it didn’t look like much—33 humdrum acres around a crumbling farmhouse in rural France, 50 miles south of the old Roman city of Poitiers. Previously a wheat field, it had been sown with grasses for grazing cattle. But I envisioned something spectacular and incredibly rare—a wild meadow seething, chirping and hopping with insect life, and, above all, a safe haven for the much beleaguered bumblebee.

I’ve spent 20 years studying bumblebees, those quintessential signs of summer and intellectual giants of the insect world. Sadly, their natural habitats are nearly gone, and some species in Europe, North America, even as far as Japan, are in rapid decline. Franklin’s bumblebee, formerly found in Oregon and California, is almost certainly extinct. To a degree, the bumblebee crisis overlaps with another bee problem you’ve heard about—colony collapse disorder, the devastating disappearance of adult commercial honeybees. Recent studies suggest that insecticides known as neonicotinoids play a role in that problem, because they can disrupt navigation and make honeybees more susceptible to disease. It makes sense that wild bees, including bumblebees, are also harmed by these chemicals.

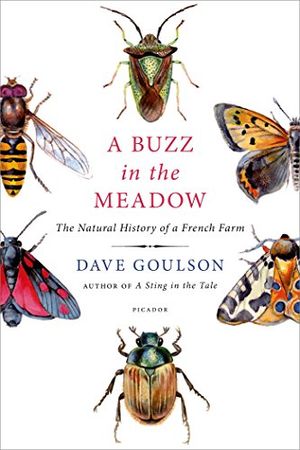

But we know for a fact that a big driver of the bumblebee decline has been the conversion of flower-rich grasslands to flower-free farm monocultures. Fragments of natural habitat that remain are often too small to support viable bee populations. Thus the French farmland, which I have been slowly reviving to wildness. It’s a true field study, chronicled in A Buzz in the Meadow, out next month.

It’s not easy restoring floral diversity on formerly arable land that has been enriched with fertilizers; the high soil fertility favors coarse grasses that out-compete the flowers. So a local farmer cuts the hay (and feeds it to his goats), which saps nutrients from the soil. As the grass weakens, flowers creep back, regenerating from the soil’s seed bank, and from seeds blowing in on the wind or carried in by birds.

Just last year, I recorded my field’s 100th new flower species, excluding those that I have sown. Every new arrival—from red clover to ladies bedstraw—supports new insects. I have dozens of butterfly, dragonfly, cricket, beetle and mantis species. From just a handful of bees, there are now 16 bumblebee species alone, including the rare short-haired bumblebee, plus honeybees and more than 50 other bee species.

These bees spill out from the meadow to pollinate the sunflowers in my neighbor’s field, and fruits and vegetables in nearby gardens. Studies around the world confirm that crop yields are more reliable when there’s a nearby patch of undisturbed habitat to act as a source of pollinators. It seems to me that if 10 percent of farmland, perhaps the least productive, were wild meadows instead, then we wouldn’t have to worry about a lack of pollination.

Though we often focus our conservation attention on large, charismatic animals, our own survival is linked far more tightly to the fate of insects and their kin. We need hoverflies, lacewings and ladybirds to eat pests; flies and dung beetles to recycle nutrients; worms and myriad other creatures to maintain our soils. And it’s the bees that pollinate our crops, providing a global service worth more than $200 billion per year. I’m learning to look after the little creatures, to find more corners for them to thrive in, for it is they that make the world go around.

Related Reads

A Buzz in the Meadow: The Natural History of a French Farm