To Save Desert Tortoises, Make Conservation a Real-Life Video Game

Traditional techniques weren’t working for the raven-ravaged reptile. So researchers got creative

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d9/6b/d96bbe92-fcfd-489d-99ba-28af4a31f794/eex088.jpg)

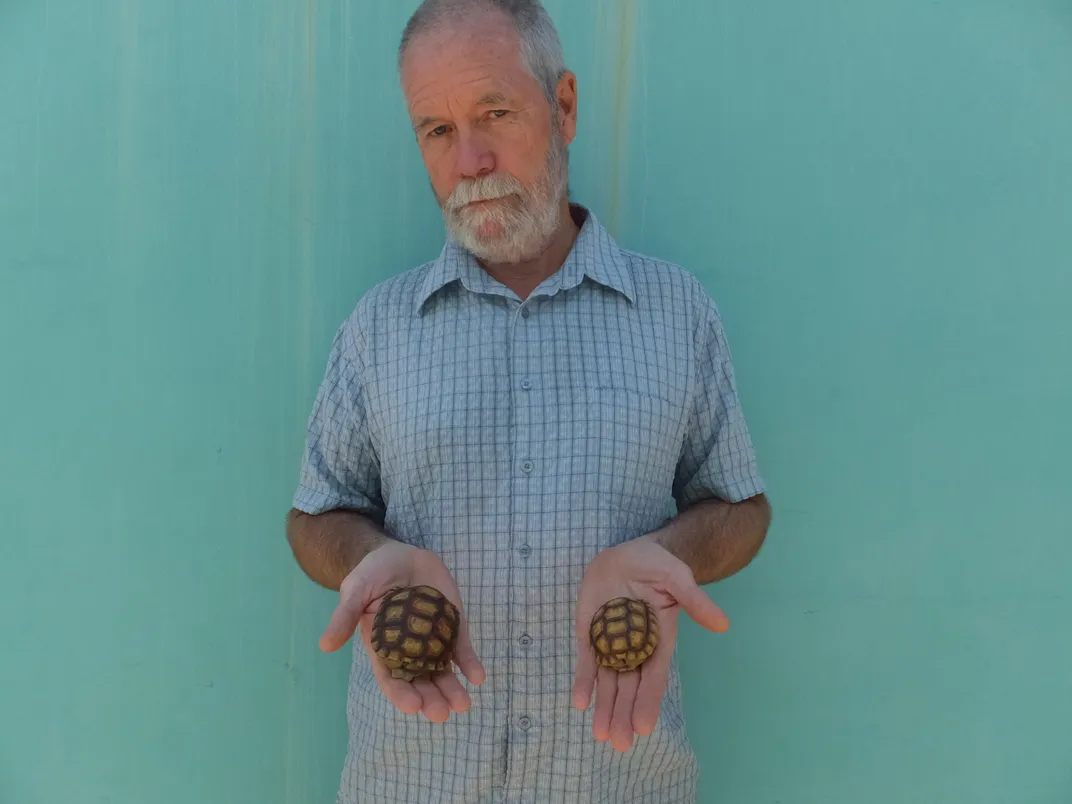

JOSHUA TREE, CA — Tim Shields holds a baby desert tortoise shell up to the sun, peering through it like a kaleidoscope. He’s carrying a container filled with these empty carapaces, perforated with coin-sized holes and picked clean of life.

Over the four decades Shields has been a wildlife biologist with the Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Geological Survey, he has watched the tortoise population in the Mojave Desert steeply decline. Where once he saw dozens of baby tortoises over the span of a season, now he can go days without spotting a single one. What he does find are these empty shells—sometimes dozens in a single nest, scattered around like discarded pistachio shells.

We’re standing in a picnic area in Joshua Tree, and Shields is showing me these hollowed-out shells to illustrate the damage. It’s easy to see how an animal could peck right through this thin casing: “It’s about as thick as a fingernail,” Shields points out. Desert tortoise shells don’t harden into a tank-like defense until the reptile is about 5 or 6 years old. Until then, hatchlings are walking gummy snacks for one of the most intelligent, adaptive and hungry desert predators: ravens.

Even before ravens, the tortoise was in trouble—and its fate has long been tied up with the history of humans. As people moved into the Mojave, the tortoise was faced with challenges its evolution could not have foreseen: off-road vehicle use, the illegal pet trade and pandemic-level respiratory disease. By 1984, biologists estimated a 90 percent population decline in desert tortoise population over the last century, thanks largely to habitat destruction. Today, an estimated 100,000 tortoises remain in the American Southwest.

According to Kristin Berry, a research scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey's Western Ecological Research Center who has been monitoring desert tortoises since the 1970s, these reptiles are an umbrella species. In other words, they require such specific conditions to survive that they are one of the best indicators of the health of the Mojave Desert ecosystem.

“It’s the proverbial canary in the mine,” adds Ron Berger, chairman and CEO of the nonprofit Desert Tortoise Conservancy and president of the nonprofit Desert Tortoise Preserve Committee. “If we can’t help this animal that can go without food or drink for years, then what are we doing to this planet?”

Humans are also culpable in aiding and abetting the tortoise’s primary threat, those pesky ravens. Over the past half century, these predatory birds have been proliferating as new sources of once-limited food and water resources become available in the form of human-made landfills, road kill, dumpsters, sewage ponds and golf courses. In direct contrast to the falling tortoise numbers, estimates place the raven population as increasing by 700 percent since 1960.

Shields remembers a pivotal moment in 2011, when he could not spot a single juvenile tortoise roaming out in the field. Instead, the only one he saw was struggling in the beak of a raven. “That moment hit me really hard,” he says. He decided that the current conservation model—monitoring tortoises, restoring their habitats and relocating them to preserves—wasn’t working. Something more innovative needed to be done.

Desert tortoises have roamed the Southwest for millions of years, adapting as the shallow inland sea transformed into the dry landscape it is today. These reptiles are crucial to their desert ecosystems. While creating their burrows, they till soil nutrients for plant life and inadvertently create hiding spots for lizards and ground squirrels. Gila monsters and coyotes eat their eggs for breakfast; roadrunners and snakes snack on juvenile tortoises; badgers and golden eagles feast on adults.

They're also a bit of a celebrity around these parts. Ironically, the same pet trade that contributed to their decline may have also contributed to the species’ iconic status: Shields wagers that the generation of Southern Californians who grew up with sweet pet tortoises have developed a nostalgic fondness for the species. As the California state reptile, they’ve cemented their position as poster-children for conservation in the desert.

In 2014, Shields founded the investor-funded company Hardshell Labs to develop a series of high-tech defense methods for protecting this beloved reptile. He hopes to use these techniques to enact a process called active ecological intervention, creating safe zones for baby tortoises throughout the desert where they can reach maturity at 15 to 20 years old and breed until, someday, the populations reach a sustainable level.

One of those methods is scattering 3D printed baby tortoises decoys, which emit irritants derived from grape juice concentrate (farmers use this chemical compound to keep birds from congregating on agricultural fields and commercial centers). Another is laser guns—TALI TR3 Counter-Piracy lasers, to be precise. These forearm-sized guns, mounted with aiming scopes that were originally used as a form of non-lethal defense for ships in the western Indian Ocean, fire a 532 nanometer green light, to which ravens’ eyes are especially sensitive.

Ravens have such sharp vision that even in the daylight, the 3-watt beam looks as solid as a pole waving in their faces. The lasers can be mounted on a rover known the Guardian Angel rover, or shot by skilled humans. Shields will aim for the ravens’ heads to get closer to their sensitive eyes if they are being persistent, but shooting within a meter’s range is usually enough to spook them.

“We once cleared a pistachio field [of ravens] in three days,” Shields says of his technological arsenal.

Perhaps the most crucial part of these technologies is that they are non-lethal. Ravens are federally protected: Though they’re native to the desert, the birds, their nests and their eggs all fall under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. And while organizations like the Coalition for a Balanced Environment argue that the boom of raven populations warrants their removal from the list in order to enhance raven management practices, many recognize their importance to the ecosystem.

Shields is among them. Even if he finds shooting near the birds with the lasers “intensely satisfying,” he doesn’t want to risk angering those who love and appreciate these birds by supporting more deadly technologies. “We’re not going to get rid of the charm of ravens, and there are people who are as charmed as ravens as I am by tortoises,” he admits. “We better acknowledge that if we’re going to find a solution.”

Instead, his technologies work with the raven’s intelligence in mind, frustrating the birds but not hurting them. Ravens are incredibly adaptive, so no single line of defense alone will work. Biologists will stake out in the desert scrub and shoot the lasers to keep the ravens on their toes. It is a skill that takes training —and time—to develop.

Now, Hardshell Labs is hoping to turn that challenge into a benefit. They’re aiming to roboticize their technologies and turn them into a sort of video game. The team hopes to tap into flow theory, the obsessiveness on solving the problem that makes gaming so addictive, in order to draw players into the game of protecting the desert tortoise.

“Environmentalism does not sell,” explains Michael Austin, Co-Founder of Hardshell Labs and Shields’s childhood friend. “What plays for people is fun and joy.”

It’s especially hard to get people to care about conservation way out in the deserts. When compared to lush biomes like rainforests, the desert has long persisted in the popular imagination as remote, barren and inhabitable, Austin says. Historically, “desert” is synonymous with “wasteland.” “The coral reefs have better PR,” he laughs.

In actuality, the desert is a place teeming with life. Because of its elevation and unique geology, the Mojave Desert especially is a unique eco-region, with 80 to 90 percent endemic plants and species found nowhere else in the world. It is also one of the most imperiled areas of the West, with over 100 of its over 2,500 species considered threatened.

Shields’ ultimate vision for Hardshell Labs is to turn armchair activists into real-time conservationists, by allowing users to remotely control techno-tortoises, lasers, and rovers online. They have already tested an early version of the game with Raven Repel, an augmented reality app in the vein of Pokémon Go. One day, he says, players from around the world will work in teams, using different tools to engage in ecological management like predation reduction, behavioral observation, fostering the spread of native plants, and preventing invasive species.

Several bird species, including the endangered sage grouse, also suffer from the ever-increasing hordes of ravens preying on their eggs. The same principles used for the decoy tortoises could be used to 3D print realistic eggs equipped with repellant, Shields says. Beyond ravens, other invasive species—the Indo-Pacific lionfish in the Caribbean, pythons in the Everglades, the Asiatic carp in the Great Lakes—could be captured by submarines controlled remotely by players. Players could even monitor video feeds over the elephant and rhinoceros habitats to spot illegal poachers.

The irony of defending nature digitally does not escape Shields. “Tortoises are so wired in to their immediate environment,” he muses. “In contrast, our species is catastrophically alienated on every level from our life support system.”

But he also recognizes the potential. A 14-year-old kid in a wheelchair could be a valued tortoise biologist, he says; a prisoner could reconnect with the world through positive contribution to the cause. In Shields’s view, denying that we are a screen culture now is delusional, so conservationists might as well make the most of it and use modern-day tools like crowdsourcing and virtual reality to leverage positive change.

“My long, long term goal is to get people to fall in love with the planet through the screen, and then realize the limitations of the screen, and then get out themselves and do it,” he says. “This is my game, and I am having so bloody much fun.”