Science Explores Our Magical Belief in the Power of Celebrity

People will pay more for memorabilia, a study finds, simply if they believe a celebrity touched it

:focal(1285x1057:1286x1058)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ae/b9/aeb9a8b4-659b-4999-86e9-ff769aaba486/marilyn_monroe.jpg)

In modern times, it's generally assumed that we've left most our of beliefs in magic or superstition behind. At the very least, we don't take them very seriously, we imagine, and certainly wouldn't pay a premium to satisfy our superstitions.

That makes a new finding by George Newman and Paul Bloom, a pair of Yale University psychologists, rather perplexing. They've found that, at auctions of celebrity memorabilia, people subconsciously weigh a history of physical contact (or lack thereof) between an item and its owner in determining how much they'll pay for it.

Their new study, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, showed that people at memorabilia auctions were willing to pay much more for items owned by John F. Kennedy or Marilyn Monroe if they thought the beloved celebrities had touched them, but preferred to pay less than the object's value for items owned by widely disliked individuals (such as Bernie Madoff) if they imagined he'd come into contact with them.

It's almost as if, the psychologists argue, these buyers believe in some sort of inexplicable mechanism that carries JFK's and Monroe's magnificent qualities—as well as Madoff's reprehensible ones—into these objects simply through touch. Their word for this nonsensical belief that's as inaccurate as the long-outdated miasma theory of disease? Contagion.

"Contagion is a form of magical thinking in which people believe that a person's immaterial qualities or essence can be transferred to an object through physical contact," they write. Their findings, they add, "suggest that magical thinking may still have effects in contemporary Western societies."

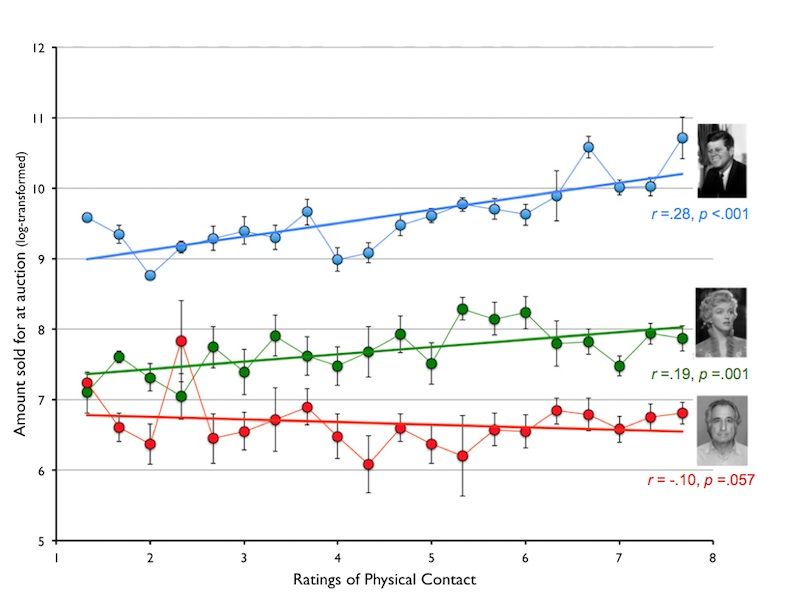

They carried out the study by looking at data sets of the prices fetched at auction by 1,297 JFK-related, 288 Monroe-related and 489 Madoff-related items—including furniture, jewelry, books and tableware—in recent years. Auction houses generally don't specify (or know) if an item was actually touched by its owner, so the researchers asked three study participants (who were blind to their hypothesis) to rate how much contact they perceived each of the items would have had with their owners on a scale of one to eight.

The idea is that buyers would likely make a similar judgment on the likelihood of contact: a wall decoration, for instance, would be less likely to have been touched by JFK, whereas a fork would probably have been handled by him frequently.

When Newman and Bloom analyzed the data, they found a significant correlation between higher ratings of expected physical contact and how much the sale price of the item exceeded the auction houses' estimated value of it. But in the case of Madoff, they found the opposite: a slight correlation between degree of contact and how much lower the sale prices were than the projections.

Interestingly, they did find an exception to this trend: extremely expensive objects. For items that sold for prices over $10,000—mostly jewelry—people did not pay any more (or less) based on a celebrity's physical contact. When it comes to truly serious, investment-level purchases, it seems, the magical belief in contagion dries up.

In addition to the real-world auction data, Newman and Bloom conducted an intriguing experiment that supports their argument about the role of physical contact in the price discrepancies. They gathered 435 volunteers and asked them how much they'd bid on a hypothetical sweater, telling some it had belonged to a famous person they admired, and others that it had been a celebrity they despised.

But they also told some of the participants that the sweater had been transformed in one of three ways: It'd been professionally sterilized (thereby, in theory, destroying the "essence" that the celebrity had left on it but not destroying the actual object), it'd been moved to the auction house (which, theoretically, could contaminate this "essence" with the touch of mere goods handlers) or it came with a condition that it could never be sold again (which would eliminate the monetary value from the participants' estimation of its worth, isolating their valuation of the sweater itself).

Compared to untransformed sweaters, the participants were willing to pay 14.5 percent less for a beloved celebrity's sweater (say, Marilyn Monroe's) that had been sterilized, but just 8.9 percent less for one they couldn't resell—indicating that they valued whatever "essence" the celebrity had passed on to the sweater by touching it more than its actual monetary value, and that this "essence" could be destroyed by sterilization. The sweater simply being handled by others in transit, however, barely affected their valuation: It seems that celebrity contact can't be so easily wiped away.

The results for sweaters owned by a despised famous person—say, Madoff—were the exact opposite. Sterilized sweaters were valued 17.2 percent higher than normal ones, and those that had simply been moved were still valued 9.4 percent higher, suggesting that eliminating a despised celebrity's "essence" is much easier, and even more crucial for the object's desirability. Not being able to resell the item affected its price similarly as it did the beloved celebrity's sweater.

Of course, all this is the kind of finding that may not surprise those who work professionally in the memorabilia industry. Last year, a John F. Kennedy-owned bomber jacket sold for $570,000. But without the power of contagion, a jacket is just a jacket—even if it was owned by JFK.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)