Science Proves Electric Eels Can Leap From Water to Attack

Biologists confirm the curious case of eels striking animals above the water’s surface

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9d/cd/9dcd87e1-f0e3-4198-ae2c-95fd1a5e82f2/electric_eel.jpg)

The local men rounded up 30 wild horses and mules from the surrounding savannah in the plains of Venezuela and forced them into a muddy pool of water filled with electric eels. It was March 19, 1800, and Alexander von Humboldt, a Prussian explorer, naturalist and geographer, was intent to conduct an open-air experiment on the power of the eels’ shock. He and his retinue watched as the fish emerged from their muddy refuge in the bottom of the pond and gathered on the surface of the water. The eels shot electric shocks, and within a few minutes, two of the horses were already stunned and drowned.

The locals kept corralling the wild horses into the pond as the eels continued to attack. An unlikely drawing produced four decades later even depicts the eels leaping right out of the water, flying through the air towards the flanks of terrified horses.

Eventually the eels lost strength and emitted less electricity. The locals gathered around the banks of the pond and perched on overhanging branches and harpooned the eels, pulling them in once the attached cords were dry enough to reduce the potential shock.

"It's what you might call a great fish story from [von Humboldt’s] adventures in South America," says Kenneth Catania, a professor of biological sciences at Vanderbilt University and the author of a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

While it’s a pivotal point of the second volume of von Humboldt’s Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America During the Years 1799-1804, the sensationalist nature of the explorer’s account and the related illustration have raised eyebrows among most modern eel biologists.

"I thought that was crazy,” Catania says. Electric eels, while fascinating animals that do use their shocking power to hunt and protect themselves, had not been known to leap out of the water or intentionally attack larger creatures. “I didn't believe that that was likely to have happened.”

Until he witnessed it himself.

While placing nets and other conductive objects in an eel tank in his lab, he noticed that the fish—especially the bigger ones—would occasionally propel themselves out of the water with their tail fins in an explosive attack and press against the invading object.

Electric eels, which are technically not eels but knifefish, are capable of emitting a shock of up to 600 volts—a force more powerful than a Taser—that they use in the wild for hunting prey.

The fish also zap for defense, stunning a potential predator before cutting a quick escape in rivers.

"The force of the currents and the depth of the water, prevent them from being caught by the Indians," von Humboldt wrote in his narrative. "They see these fish less frequently than they feel shocks from them when swimming or bathing in the river.”

But to actually go out of their way to attack a large animal seemed counterintuitive until Catania made the connection between what was happening in the tanks and von Humboldt’s account.

The explorer was visiting in March, which is usually the dry season in the Llanos, or great plains, area of Venezuela. Many of the wetlands in the Llanos evaporate during this time, trapping aquatic life like electric eels in small ponds, which aren’t unlike Catania’s aquariums. In both situations, the eels have nowhere to escape and might be forced into the offense to protect themselves from potential predators.

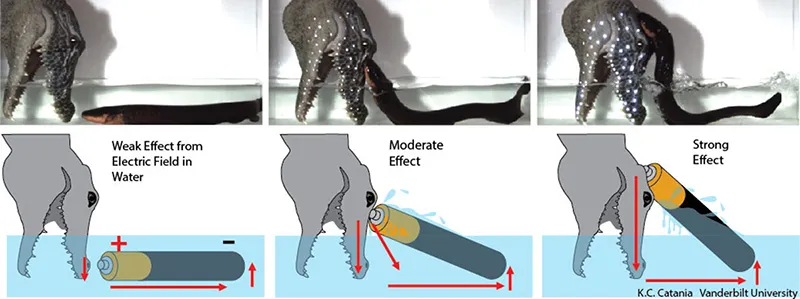

So when Catania dangled conductive materials into his eel tank in the shape of things like human arms or crocodile heads, the knifefish jumped partly out of the shallow water and attacked, rubbing their heads against the invading object for several seconds.

Meanwhile microphones the biologist had placed inside the tank confirmed the attacks were coordinated with a high voltage volley. "Importantly, they're not just leaping randomly. They're really following the conductor out of the water,” he says. "It's fascinating to me because it's clearly a very impressive and very useful defense mechanism."

In a sense, the aggressive behavior of the eels facilitates Catania’s job.

Previously, researchers would take eels out of the water and put them on a table to measure the voltage of their strikes—an ordeal that was far from pleasant for the fish and for the researchers trying to manage the slippery, sometimes more than six-foot-long electrified fish.

Von Humboldt wasn’t able to take adequate safety precautions in his time. After putting both his feet on an eel freshly pulled from the water, the explorer experienced a "dreadful shock" that led to violent pain in his knees and most of his joints for the rest of the day.

Catania himself has been shocked by accident while handling the eels, and though it’s a tough force to describe in layman’s terms, he says it's something like the zap you might feel from a wall socket.

But through his stimulating research he determined that eels use a sophisticated sense of electro-reception to identify conductors, which they probably interpret as living things (they usually won’t attack non-conductors like plastic).

Now that Catania is more familiar with the eels' behavior, he can use the knowledge to his advantage as they will swim up of their own accord and shock a metal plate hooked to a voltmeter.

He has found that the eels can deliver a more concentrated shock by projecting out of the water and pressing their chins against animals. "The eels may not be very good at shocking something that's not fully in the water so this behavior is the solution,” he says. "The higher [the eel] gets, the more of that power goes through what it's touching and the less goes back through the water from its tail. These eels have evolved to have remarkable output, and it turns out they have evolved pretty remarkable behavior to go along with that."

Other researchers skeptical about von Humboldt’s account were also convinced after watching the videos Catania produced of electric eels attacking conductors.

"In combination with [Catania’s] previous studies, these results are literally rewriting the book on what we know about electric behaviors of the electric eel," says James Albert, a biologist at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette who has studied how eels evolved their ability to use electricity to their favor. "Ken is an amazing experimentalist with a fine eye for observing the nuances of animal behavior."

As for von Humboldt, he and his retinue left Calabozo on March 24, "highly satisfied" with their stay and the experiments they had conducted on an object "so worthy of the attention of physiologists." He would eventually go on to explore the Orinoco and Amazon rivers, among other parts of the Americas, publishing his accounts and discussing them personally with the likes of Simón Bolívar, future liberator of much of Spanish South America.

The explorer’s naturalist legacy is still honored today in a number of ways, among them the name of a powerful movement of water that thrusts northwards up the coast of Chile and Peru: The Humboldt Current.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joshua-learn_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joshua-learn_copy.jpg)