Spinops: The Long-Lost Dinosaur

Spinops was one funky looking dinosaur, and its discovery emphasizes the role of museum collections. Who knows what else is waiting to be rediscovered?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111207121012spinops_life-thumb.jpg)

Almost a century ago, skilled fossil collectors Charles H. Sternberg and his son Levi excavated a previously unknown horned dinosaur. Paleontologists didn’t realize the importance of the discovery until now.

The long-lost dinosaur was sitting right underneath paleontologist’s noses for decades. In 1916, while under commission to find exhibit-quality dinosaurs for what is now London’s Natural History Museum, the Sternbergs discovered and exhumed a dinosaur bonebed in the northwestern part of what is now Dinosaur Provincial Park in Canada. Among the haul were several portions of a ceratopsid skull. Some parts, such as the upper and lower jaws, were missing, but portions of the frill and a piece preserving the nasal horn, eye sockets and small brow horns were recovered. Although there was apparently not much to go on, the Sternbergs thought this dinosaur might be a new species closely related to the many-horned Styracosaurus.

Authorities at the London museum were unimpressed with what the Sternbergs sent over. Museum paleontologist Arthur Smith Woodward wrote to the Sternbergs that their shipment from the ceratopsid site was “nothing but rubbish.” As a result, the fossil collection was shelved and left mostly unprepared for 90 years. The museum had no idea there was a new dinosaur collecting dust. It wasn’t until 2004, when Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology scientist Andrew Farke was rummaging through the museum’s collections during a visit, that the long-lost dinosaur was rediscovered.

We hear plenty about the struggles and adventure of digging up dinosaurs in the field. We hear far less about those finds that had been hidden away in museum collections—important specimens of already-known dinosaurs or previously-unknown species. I asked Farke how he rediscovered what the Sternbergs had found so long ago:

I first saw the specimen back in 2004, when I was over in the U.K. filming for “The Truth About Killer Dinosaurs.” I had a few hours to myself, so I arranged for access to the collections at the Natural History Museum. In browsing the shelves, I ran across these partially prepared ceratopsian bones. The thing that really caught my eye was this piece of the frill—the parietal bone. It was upside down and embedded in rock and plaster, but I saw what looked like two spikes sticking out the back of it. My first thought was that it was Styracosaurus, but something just didn’t look right. Could it possibly be a new dinosaur?! I spent a long time trying to convince myself that it was just a funky Styracosaurus, or that I was misinterpreting the bones. When I got back home, I chatted with Michael Ryan about it, and he was very surprised to hear about it too. Apparently it was this legendary specimen—Phil Currie had snapped a photo of it back in the 1980s, and Michael hadn’t been able to relocate it when he visited London himself. One way or another, I was the first person to relocate and recognize the fossil. So, we contacted Paul Barrett (dinosaur curator at the NHM), and Paul was able to arrange to get the specimen fully prepared.

When the dinosaur was fully prepped and studied by Farke, Ryan and Barrett with colleagues Darren Tanke, Dennis Braman, Mark Loewen and Mark Graham, it turned out that the Sternbergs had been on the right track. This Late Cretaceous dinosaur truly was a previously unknown animal closely related to Styracosaurus. The paleontologists named the animal Spinops sternbergorum as a reference to the dinosaur’s spiny-looking face and as a tribute to the Sternbergs.

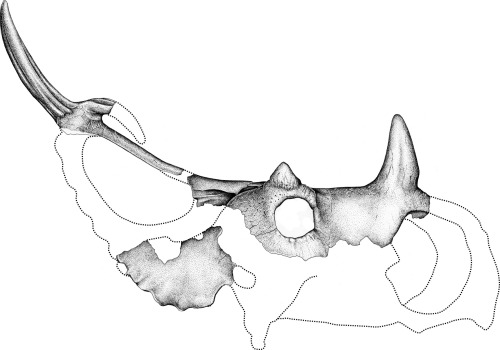

A reconstruction of the Spinops skull, with grey areas representing the bones known to date. Copyright Lukas Panzarin, courtesy of Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology

Rather than being something wildly different, Spinops looks rather familiar. As Farke put it, this centrosaurine dinosaur “is like the love child of Styracosaurus and Centrosaurus,” the latter being a common horned dinosaur with a deep snout, large nasal horn, small brow horns and distinctive frill ornamentation. Whereas Spinops is like Centrosaurus in having two, forward-curving hooks near the middle of the frill, Farke notes, the two large spikes sticking out of the back of the frill in Spinops are more like the ornaments of Styracosaurus. Given these similarities, it might be tempting to think that the dinosaur just named Spinops was really just an aberrant Centrosaurus or Styracosaurus, but this doesn’t seem likely. “e have two specimens of Spinops that show the same frill anatomy,” Farke says, “so we can be confident that this is a genuine feature and not just a freak example of Styracosaurus or Centrosaurus.”

Nor does Spinops appear to be just a growth stage of a previously known dinosaur. Over the past few years there has been a growing debate among paleontologists about the possibility that some dinosaurs thought to be distinct species were really just older or younger individuals of species that were previously named. (The idea that Torosaurus represents the skeletally mature form of Triceratops is the best-known example.) Horned dinosaurs, especially, have come under scrutiny in this lumping/splitting argument, but Spinops seems to be the real deal. Farke explains, “We have excellent growth series for Styracosaurus and Centrosaurus (the two closest relatives of Spinops), and nothing in their life history looks like Spinops—young or old. There’s no way to “age” Spinops into an old or young individual of another known horned dinosaur.”

This has significant implications for our understanding of how many dinosaurs were running around in the Late Cretaceous of what is now Canada. According to Farke, there are now five known species of centrosaurine dinosaurs within the series of rocks containing the Oldman Formation and Dinosaur Park Formation (spanning about 77.5 million to 75 million years ago). Not all of these dinosaurs lived beside each other at the same time, though, and determining exactly where Spinops fits is difficult because paleontologists have been unable to relocate the Sternberg quarry. Paleontologists are still trying to do so. A combination of fossil pollen from the rock Spinops was preserved in and historical documentation have allowed paleontologists to narrow down the area where Spinops was probably excavated, and Farke says he’s “cautiously optimistic that will be relocated—maybe not tomorrow, but hopefully in the next few decades.”

Pinning down where Spinops came from and exactly when it lived will be important to understanding how horned dinosaurs evolved during the Late Cretaceous. Such geological resolution would allow paleontologists to investigate whether Spinops was close to the ancestral line of Styracosaurus or was a more distant relative, Farke said. Perhaps continued prospecting will even turn up new specimens of Spinops from other locations. “We know the general area and rock level where Spinops came from,” Farke explained. “I think it’s just a matter of time and fossil collecting to find more!” Additional fossils would certainly be welcome, especially because there are plenty of questions about what Spinops means for our understanding of centrosaurine evolution. As Farke and co-authors lay out at the conclusion of the new paper, questions such as “Do the ceratopsians preserved here document anagenesis or cladogenesis ? How are the taxa of Alberta related to those from elsewhere? Was Spinops a rare element of the Campanian fauna, or will more remains be recognized?” remain to be answered.

For me, at least, the discovery of a new ceratopsid dinosaur is always cause for celebration. Sadly, though, some of the media coverage of this well-ornamented dinosaur has been less than stellar. Gawker led in with “Moron paleontologists find new species of dinosaur in their own museum.” At least when they decide to miss the point, they really commit to that approach. Whatever scientific content there is in the news is overwhelmed by meanspirited snark, although, as some folks pointed out when I expressed my frustration about the piece on Twitter last night, Gawker is meant to be a joke site. Fair enough. In that case, getting your science news from them is about as productive as asking your friend who lives in a symbiotic relationship with the couch and is fueled almost entirely by Mr. Pibb for dating advice.

Juvenile snark is one thing. Trotting out the old “missing link” mistake is another. The Huffington Post fell into that trap when they ran their story “Spinops Sternbergorum: New Dinosaur Species Discovered, Could Be Missing Link.” *Facepalm* First off, there is presently no way to know whether Spinops was ancestral to any other kind of dinosaur. Farke and colleagues were able to determine the relationships of the new dinosaur compared to those already known—that is, they could tell who is more closely related to whom—but dinosaur paleontologists typically draw ancestor-descendant ties only in the case of exceptional and well-constrained evidence. In this case, especially, Farke and co-authors reject the hypothesis that Spinops was an intermediate form between Centrosaurus and Styracosaurus, and the scientists emphasize caution in hypothesizing about the relationships of Spinops to these dinosaurs until more data is found. The “missing link” hook is entirely unwarranted. Furthermore, the phrase “missing link” is closely tied to a linear view of evolution that obscures the deep, branching patterns of change over time, and there’s even a basic semantic issue here. When paleontologists find what the uninformed call a “missing link,” that link is no longer missing!

Media blunders aside, Spinops surely was a funky looking dinosaur, and the centrosaurine’s discovery emphasizes the role collections can play in our growing understanding of dinosaurs. There are far more dinosaur specimens than paleontologists, and there are still plenty of field jackets and specimens that have been left unprepared. Who knows what else is out there, waiting to be rediscovered? There is certainly an air of romance about fieldwork and hunting down dinosaurs, but there are surely fascinating, unknown dinosaurs hiding in plain sight.

References:

Farke, A.A., Ryan, M.J., Barrett, P.M., Tanke, D.H., Braman, D.R., Loewen, M.A., and Graham, M.R (2011). A new centrosaurine from the Late Cretaceous of Alberta,

Canada, and the evolution of parietal ornamentation in horned dinosaurs Acta Palaeontologica Polonica : 10.4202/app.2010.0121

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)