The Surprising Way Civil War Took Its Toll on Congo’s Great Apes

Using satellite maps and field studies, scientists found that even small disturbances to the forest had big consequences for bonobos

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bd/94/bd940434-5e85-4b6f-a492-476f264e7738/ykym-img_1769.jpg)

Even the most celebrated conservation successes can seemingly be undone overnight. That was the hard lesson Takeshi Furuichi learned when conflict erupted in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), threatening the survival of bonobo populations that he and his colleagues had been studying and protecting for decades.

Amidst growing turmoil and brutal violence in the mid 1990s, the researchers—their lives potentially at risk—had no choice but to reluctantly return to Japan and hope the best for the animals and people they left behind.

“It’s really difficult, because nature and bonobos remain the same, but human society changes very rapidly,” explains Furuichi, a primatologist at Kyoto University. “I can’t think, ‘Yes, OK, we are now in a successful balance,’ because I know that next year it will change again. It’s an endless effort.”

Six years would pass before Furuichi and his colleagues resumed their studies. When they finally returned to the DRC in 2002, their fears concerning the war’s toll were confirmed: Some groups of bonobos had disappeared altogether, while others that survived had been reduced to fewer than half their original members.

Crestfallen but determined to derive some meaning from the years of upheaval, the researchers set out to discover the precise drivers behind the bonobos’ downfall. Their work has yielded surprising results that could inform the work of conservationists and benefit other endangered great apes—valuable findings that may make the loss of the DRC bonobos not completely in vain.

Although habitat destruction due to logging and industrial agriculture—including palm oil cultivation—currently ranks as the greatest threat to great ape populations, Furuichi and his colleagues discovered that it is not only these massive disturbances that cause widespread decline. As the bonobos' fading populations unfortunately showed, even disruptions on a relatively minor scale—a forest clearing here, an uptick in hunting there—can have devastating impacts.

The DRC “bonobo case study confirms to us the need for a very cautious approach to developing land where apes are found,” says Annette Lanjouw, vice president of strategic initiatives and the Great Ape Program at the Arcus Foundation, a non-profit that promotes diversity among people and nature. “The findings place a huge emphasis on avoiding disturbance as opposed to saying, ‘It’s OK if we disturb this area, they’ll come back or we’ll repair it afterward.’”

This lesson could significantly inform conservationists’ efforts to devise better strategies for protecting great apes and their habitats in the face of a rapid assault by timber harvesting, industrial agriculture and other development.

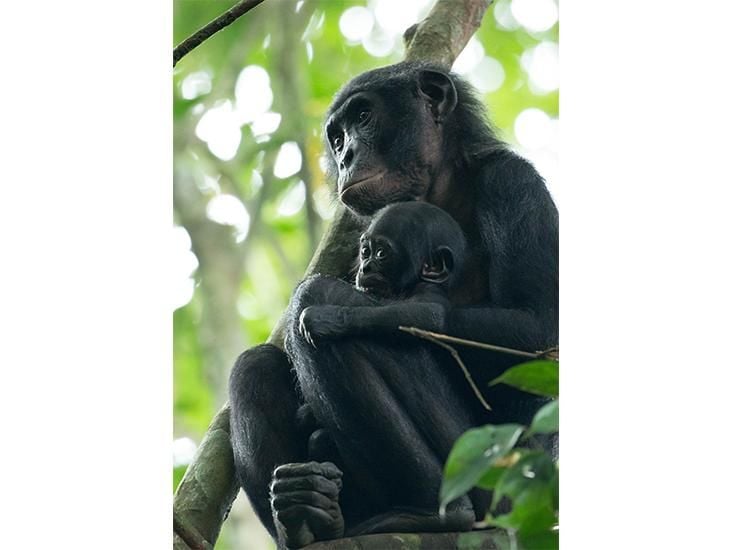

Bonobos in Paradise

Sometimes called “the forgotten ape,” primatologists long overlooked bonobos. While gorillas and chimpanzees were well known by the 16th century, it wasn’t until 1929 that bonobos were officially described as a species. Their late arrival on the scientific scene is partly due to their looks: They so closely resemble chimps that any early explorers who encountered them likely did not recognize the animal’s novelty. Bonobos also live in a relatively small and difficult to reach area, the deep jungle of the Congo River’s left bank.

Once their existence was declared, however, news of the world’s fourth great ape species travelled fast, and bonobos soon appeared in collections and zoos, where primatologists began studying them. Wild bonobos, however, would retain their air of inscrutable mystery until 1973, when Takayoshi Kano, a young primatologist from Kyoto University, established the world’s first bonobo field study site.

Kano had been biking around the Congo Basin in search of bonobos when he came across a village called Wamba, located in what was then called the country of Zaïre, now the DRC. Kano quickly realized that Wamba possessed everything he could hope for in a field site. Situated on the Luo River against a backdrop of thick forest, the village offered excellent access to local bonobo populations.

More than that, though, Wamba’s human residents already had a special relationship with the apes: They believed bonobos to be their direct relatives. They told Kano that many years in the past a young bonobo male grew tired of eating raw food, so abandoned his great ape family. God heard his anguished cries and took pity by helping him make fire, which he used to cook his food. This bonobo eventually built a village—present day Wamba—meaning that all modern villagers are descended from him. That’s why people living there today neither hunt nor eat bonobos.

Kano set about establishing a formal study site. Other researchers—including Furuichi—soon joined him. For 20 years they observed the bonobos, which thrived in conditions of near absolute peace. Once, in 1984, an outsider poached a young adult male, and a few years later, soldiers trapped a few baby animals, supposedly as a gift for a visiting dignitary. But otherwise, the animals were left alone, their populations steadily rising.

Kano, Furuichi and their colleagues gained unprecedented insights into bonobo behavior, evolution and life history. They observed the species day in and out, watching families develop and coming to intimately know individual study subjects.

The Japanese team, collaborating with local Congolese partners, established the 479- square kilometer (185-square mile) Luo Scientific Reserve, a protected area encompassing Wamba and four other human settlements. Local people benefited too: They were still allowed to hunt for food inside the reserve using traditional bow and arrows or snares, but now they enjoyed a bonus—an influx of money from international researchers who regularly visited the site.

For a while, all was well. Local people were reaping the rewards of conservation, yet still able to use of their forest; the researchers were gathering remarkable amounts of data and insight into the world’s most enigmatic ape species; and the animals in the reserve were flourishing.

Then came the civil war.

Conservation’s Tipping Balance

The first hint of trouble began in 1991, when riots broke out in Kinshasa, the nation’s capital. As the political and economic situation deteriorated, city people began fleeing to rural areas. By 1996, the country officially plunged into civil war, and Furuichi and his colleagues had no choice but to leave.

Millions died over the ensuing years, and animals also suffered. In one reserve, elephant densities decreased by half during the war years. Bushmeat sales in one urban market shot up by 23 percent, and meat cuts from large animals such as gorillas, elephants and hippos began appearing more frequently. The wildlife fed a country’s hungry people.

Unable to safely return to the DRC, Furuichi could only guess at how the Wamba bonobos were doing. In 2002, he and his colleagues finally gained a brief window of insight into the apes’ fate when they returned as part of a National Geographic expedition. They found soldiers occupying their research station, and learned that the Congolese government had stationed troops throughout the forest.

The military men hailed from many different tribes; most did not have strong traditional taboos against killing and eating bonobos. The scientists heard stories of soldiers hunting the animals, or of forcing villagers to kill bonobos for them. One man, a long-time research assistant, was repeatedly asked by soldiers to lead them to the apes’ sleeping place. At first he led them astray, but soon the armed men, fed up, threatened to kill him if he did not reveal the animals’ hiding spot. He complied.

In 2003, a ceasefire was at last declared. The scientists returned to their research station and began the long process of trying to piece together what had happened during their absence. They found that three of the six groups of bonobos in the northern section of the reserve had disappeared entirely. Numbers had dropped from 250 in 1991 to around 100 in 2004. Only the main study group seemed to be in fair shape compared to pre-war times, likely thanks to the protection of the Wamba community.

But what exactly had caused the severe declines? The researchers teamed up with spatial mapping experts to see if the forest itself could offer clues. The team compiled satellite images from 1990 to 2010, and analyzed forest loss and fragmentation over time throughout Luo and a neighboring reserve.

The first ten years of that period, they found, saw almost double the rate of forest loss as the postwar decade, especially in remote areas far from roads and villages. This deforestation, however, was not a case of clear-cutting or wide scale slash-and-burn. Instead the researchers observed only small patches of disturbance—perforations in an otherwise uninterrupted blanket of green—scattered throughout the reserve.

Interviews with locals completed the story told by the satellite imagery. “During the war, people were migrating away from their natal villages [and urban centers], and hiding out in the forest to escape rebel soldiers,” explains Janet Nackoney, an assistant research professor of geographical sciences at the University of Maryland who led the spatial analysis study.

These people were refugees who had either forgotten taboos or never had them to begin with. They began killing the apes for food. Some locals, likely driven by hunger, hunted bonobos too, despite traditional beliefs.

Forest camps—openings in the canopy—provided easy access to the formerly remote areas where bonobos lived, Furuichi says, while guns (which multiplied during the war) proved much more effective at killing the animals than traditional bow and arrows.

“These findings tell us what we would assume to be true: that people are enormously destructive, particularly people who are hunting and invading the forest,” Lanjouw says. “When that happens, wildlife populations, including bonobos, disappear.” Though the forests may remain, they are empty of their former animal residents.

Precarious Existence

Bonobos still live in the Luo Scientific Reserve, but their future prospects are far from certain. While the main study group’s population is increasing again and has even exceeded pre-war numbers, bonobos living in the southern section of the reserve are faring less well and can no longer be found in some places where they once lived. Interviews with people today reveal that at least half the Wamba villagers still hold on to their traditional taboos, but those living in neighboring villages usually do not cite taboos as a reason for sparing bonobos. Instead, they refrain from hunting because they expect to get some benefit—employment or aid—from foreigners coming to do conservation work or science.

“Where research activities are undertaken, people are eager to protect the animals,” Furuichi says. “But in areas where research is not going on, people probably do not hesitate to kill and eat bonobos.”

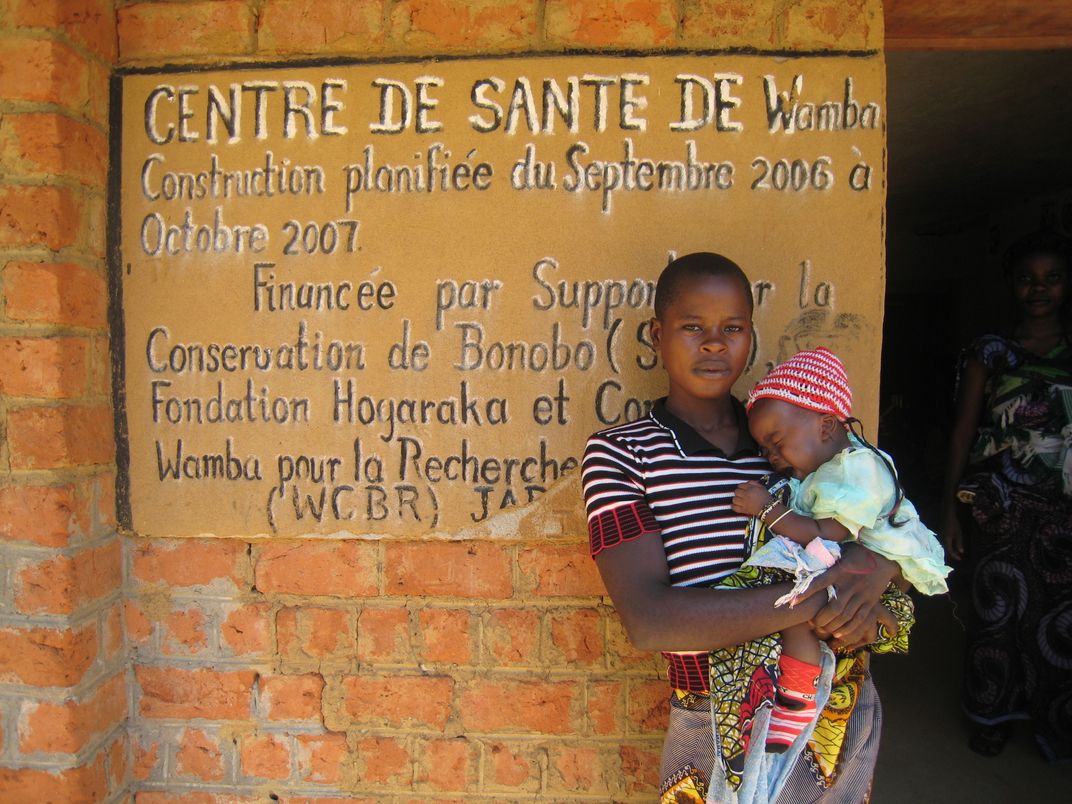

In their efforts to win over the people of the communities where they work, the scientists now support education for local children and have built a small hospital. They also employ some community members, though the perceived discrepancy between the rewards received by one individual over another can lead to problems, with someone occasionally, “thinking that their colleagues are getting many more benefits than them,” so they kill a bonobo out of spite, Furuichi says.

Indeed, when the scientists are in good standing with the community, the frequency of illegal activities drops, he reveals, but when there are disagreements, the researchers hear an increasing number of gunshots in the forest. “That’s kind of a barometer for the success of our public relations,” Furuichi says. “It’s frustrating.”

Community expectations are also steadily getting bumped up. While a few donations and small salaries used to be enough to keep locals happy, now community politicians sometimes approach the researchers saying, “‘If you want to continue this research, you have to create a paved airstrip for us’ or something like that,” Furuichi says. “They know how people in Japan and the U.S. live, and they want to be equal.”

Despite these complications, Furuichi does not think that strictly enforced exclusive protection zones, where all human activity is banned, are a solution. Such an approach often unfairly impacts local people, and protected or not, closed preserves are still vulnerable to poaching and habitat destruction.

Instead, he says, if Japan and other nations truly believe bonobos are worth saving, then those countries should help establish a system in which local people can get more benefits from conserving those animals than by hunting them and cutting trees. “We can’t just say they should protect animals because the animals are very important,” he says.

Such aid, however, is not likely to arrive soon on a national or continent-wide scale.

Compounding conservationists’ problems: Global consumption of natural resources is escalating rapidly, fueled by growing human populations and rising living standards. Development—whether it takes the form of logging; palm oil, soy, rubber or coffee plantations; mineral extraction; road and town building; or the bushmeat trade—is intensifying pressure on the world’s remaining habitat. For bonobos and other great apes, the consequences could be extinction. And as Furuichi and his colleagues showed, the disappearance of such species does not require the wholesale destruction of forests.

“We are slowly and inexorably seeing populations decrease all across the continent,” Lanjouw says bluntly. “If we continue to develop land as recklessly as we currently are, we will see the disappearance of these creatures.”

Furuichi concurs. “In some protected areas, bonobos may survive in the future, but in other places, the current situation is very, very dangerous for their continued survival,” he says. “I myself am quite pessimistic about the future of great ape conservation in Africa.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)