Why Doesn’t Anyone Know How to Talk About Global Warming?

The gap between science and public understanding prevents action on climate change—but social scientists think they can fix that

:focal(2786x530:2787x531)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ef/8a/ef8a790d-708a-4f57-bf0d-4a70a0ae9de0/42-39658200.jpg)

When Vox.com launched last month, the site's editor-in-chief, Ezra Klein, had a sobering message for us all: more information doesn't lead to better understanding. Looking at research conducted by a Yale law professor, Klein argued that when we believe in something, we filter information in a way that affirms our already-held beliefs. "More information...doesn’t help skeptics discover the best evidence," he wrote. "Instead, it sends them searching for evidence that seems to prove them right."

It's disheartening news in many ways—for one, as Klein points out, it cuts against the hopeful hypothesis set out in the Constitution and political speeches that any disagreement is merely a misunderstanding, an accidental debate caused by misinformation. Applied to our highly polarized political landscape, the study's results make the prospect of change seem incredibly difficult.

But when applied to science, the results become more frightening. Science, by definition, is inherently connected to knowledge and facts, and we rely on science to expand our understanding of the world around us. If we reject information based on our personal bias, what does that mean for science education? It's a question that becomes especially relevant when considering global warming, where there appears to be an especially large chasm between scientific knowledge and public understanding.

"The science has become more and more certain. Every year we’re more certain of what we’re seeing," explains Katharine Hayhoe, an atmospheric scientist and associate professor of political science at Texas Tech University. 97 percent of scientists agree that climate change is happening, and 95 percent of scientists believe that humans are the dominant cause. Think of it another way: over a dozen scientists, including the president of the National Academy of Sciences, told the AP that the scientific certainty regarding climate change is most similar to the confidence scientists have that cigarettes contribute to lung cancer. And yet as the scientific consensus becomes stronger, public opinion shows little movement.

"Overall, the American public’s opinion and beliefs about climate change haven’t changed a whole lot," says Edward Maibach, director of George Mason University's Center for Climate Change Communication. "In the late 90s, give or take two-thirds of Americans believed that climate change was real and serious and should be dealt with." Maibach hasn't seen that number change much—polls still show about a 63 percent belief in global warming—but he has seen the issue change, becoming more politically polarized. "Democrats have become more and more convinced that climate change is real and should be dealt with, and Republicans have been going in the opposite direction."

It's polarization that leads to a very tricky situation: facts don't bend to political whims. Scientists agree that climate change is happening—and Democrats and Republicans alike are feeling its effects now, all over the country. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) keeps reiterating that things look bleak, but avoiding a disaster scenario is still possible if changes are made right now. But if more information doesn't lead to greater understanding, how can anyone convince the public to act?

***

In the beginning, there was a question: what had caused the glaciers that once blanketed the Earth to melt? During the Ice Age, which ended around 12,000 years ago, glacial ice covered one-third of the Earth's surface. How was it possible that the Earth's climate could have changed so drastically? In the 1850s, John Tyndall, a Victorian scientist fascinated by evidence of ancient glaciers, became the first person to label carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas capable of trapping heat in the Earth's atmosphere. By the 1930s, scientists had found an increase in the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere—and an increase in the Earth's global temperature.

In 1957, Hans Suess and Roger Revelle published an article in the scientific journal Tellus that proposed that carbon dioxide in the atmosphere had increased as a result of a post-Industrial Revolution burning of fossil fuels—buried, decaying organic matter that had been storing carbon dioxide for millions of years. But it wasn't clear how much of that newly released carbon dioxide was actually accumulating in the atmosphere, versus being absorbed by plants or the ocean. Charles David Keeling answered the question through careful CO2 measurements that charted exactly how much carbon dioxide was present in the atmosphere—and showed that the amount was unequivocally increasing.

In 1964, a group from the National Academy of Sciences set out to study the idea of changing the weather to suit various agricultural and military needs. What the group members concluded was that it was possible to change climate without meaning to—something they called "inadvertent modifications of weather and climate"—and they specifically cited carbon dioxide as a contributing factor.

Politicians responded to the findings, but the science didn't become political. The scientists and committees of early climate change research were markedly bipartisan, serving on science boards under presidents both Democrat and Republican. Though Rachel Carson's Silent Spring, which warned of the dangers of synthetic pesticides, kicked off environmentalism in 1962, the environmental movement didn't adopt climate change as a political cause until much later. Throughout much of the '70s and '80s, environmentalism focused on problems closer to home: water pollution, air quality and domestic wildlife conservation. And these issues weren't viewed through the fracturing political lens often used today—it was Republican President Richard Nixon who created the Environmental Protection Agency and signed the National Environmental Policy Act, the Endangered Species Act and a crucial extension of the Clean Air Act into law.

But as environmentalists championed other causes, scientists continued to study the greenhouse effect, a term coined by the Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius in the late 1800s. In 1979, the National Academy of Sciences released the Charney Report, which stated that "a plethora of studies from diverse sources indicates a consensus that climate changes will result from man's combustion of fossil fuels and changes in land use."

The scientific revelations of the 1970s led to the creation of the IPCC, but they also caught the attention of the Marshall Institute, a conservative think tank founded by Robert Jastrow, William Nierenberg and Frederick Seitz. The men were accomplished scientists in their respective fields: Jastrow was the founder of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, Nierenberg was the former director of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and Seitz was the former president of the United States National Academy of Sciences. The institute received funding from groups such as the Earhart Foundation and the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, which supported conservative and free-market research (in recent years, the institute has received funding from Koch foundations). Its initial goal was to defend President Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative from scientific attacks, to convince the American public that scientists weren't united in their dismissal of the SDI, a persuasive tactic which enjoyed moderate success.

In 1989, when the Cold War ended and much of the Marshall Institute's projects were no longer relevant, the Institute began to focus on the issue of climate change, using the same sort of contrarianism to sow doubt in the mainstream media. It's a strategy that was adopted by President George W. Bush's administration and the Republican Party, typified when Republican consultant Frank Luntz wrote in a memo:

"Voters believe that there is no consensus about global warming within the scientific community. Should the public come to believe that the scientific issues are settled, their views about global warming will change accordingly. Therefore, you need to continue to make the lack of scientific certainty a primary issue in the debate."

It's also an identical tactic to one used by the tobacco industry to challenge research linking tobacco to cancer (in fact, Marshall Institute scientist Seitz once worked as a member of the medical research committee for the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company).

But if politicians and strategists created the climate change "debate," the mainstream media has done its part in propagating it. In 2004, Maxwell and Jules Boykoff published "Balance as bias: global warming and the US prestige press," which looked at global warming coverage in four major American newspapers: the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal, between 1988 and 2002. What Boykoff and Boykoff found was that in 52.65 percent of climate change coverage, "balanced" accounts were the norm—accounts that gave equal attention to the view that humans were creating global warming and the view that global warming was a matter of natural fluctuations in climate. Nearly a decade after the Charney Report had first flagged man's potential to cause global warming, highly-reputable news sources were still presenting the issue as a debate of equals.

In a study of current media coverage, the Union of Concerned Scientists analyzed 24 cable news programs to determine the incidence of misleading climate change information. The right-leaning Fox News provided misinformation on climate change in 72 percent of its reporting on the issue; left-leaning MSNBC also provided misinformation in 8 percent of its climate change coverage, mostly from exaggerating claims. But the study found that even the nonpartisan CNN misrepresented climate change 30 percent of the time. Its sin? Featuring climate scientists and climate deniers in such a way that furthers the misconception that the debate is, in fact, still alive and well. According to Maibach, the continuing debate over climate science in the media explains why fewer than one in four Americans know how strong the scientific consensus on climate change really is. (CNN did not respond to requests for a comment, but the network hasn't featured a misleading debate since February, when two prominent CNN anchors condemned the network's use of debate in covering climate change.)

Sol Hart, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan, recently published a study looking at network news coverage of climate change—something that nearly two-thirds of Americans report watching at least once a month (only a little over a third of Americans, by contrast, reported watching cable news at least once a month). Looking at network news segments about climate change from 2005 to mid-2011, Hart noticed what he perceived as a problem in the networks' coverage of the issue, and it wasn't a balance bias. "We coded for that, and we didn’t see much evidence of people being interviewed on network news talking about humans not having an affect on climate change," he explains.

What he did notice was an incomplete narrative. "What we find is that the impacts and actions are typically not discussed together. Only about 23 percent of all articles on network news talked about impacts and actions in the same story. They don’t talk about them together to create a cohesive narrative."

But is it the media's responsibility to create such a narrative?

In the decades before the digital revolution, that question was easier to answer. Legacy media outlets historically relied on balance and impartiality; it wasn't their place, they figured, to compel their readers to act on a particular issue. But the information revolution, fueled by the web, has changed the media landscape, blurring the lines between a journalist's role as a factual gatekeeper and an activist.

"With the advent of digital online, there’s a lot more interaction with the audience, there’s a lot more contributions from the audience, there’s citizen journalists, there’s bloggers, there’s people on social media. There are tons and tons of voices," Mark Glaser, executive editor at PBS MediaShift, explains. "It’s hard to just remain this objective voice that doesn’t really care about anything when you’re on Twitter and you’re interacting with your audience and they’re asking you questions, and you end up having an opinion."

***

For a long time, climate change has been framed as an environmental problem, a scientific conundrum that affects Arctic ice, polar bears and penguins; a famously gut-wrenching scene from Al Gore's An Inconvenient Truth mentions polar bears having drowned looking for stable pieces of ice in a warming Arctic Ocean. It's a perfectly logical interpretation, but increasingly, climate scientists and activists are wondering whether or not there's a better way to present the narrative—and they're turning to social scientists, like Hart, to help them figure that out.

"Science has operated for so long on this information deficit model, where we assume that if people just have more information, they’ll make the right decision. Social scientists have news for us: we humans don’t operate that way," Hayhoe explains. "I feel like the biggest advances that have been made in the last ten years in terms of climate change have been in the social sciences."

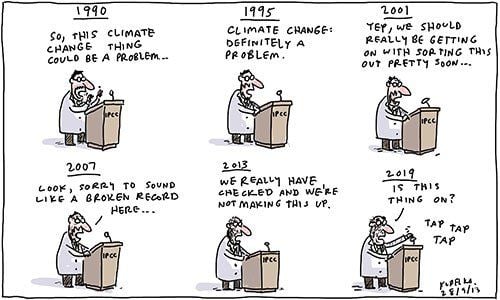

As Hayhoe spoke about the frustrations of explaining climate change to the public, she mentioned a cartoon that circulated around the internet after the IPCC's most recent report, drawn by Australian cartoonist Jon Kudelka.

"I think that my colleagues and I are becoming increasingly frustrated with having to repeat the same information again and again, and again and again and again—and not just year after year, but decade after decade," Hayhoe says.

In other countries around the world, the climate change message appears to be getting through. In a Pew poll of 39 countries, global climate change was a top concern for those in Canada, Asia and Latin America. Looking at data from all included countries, a median of 54 percent of people placed global climate change as their top concern—in contrast, only 40 percent of Americans felt similarly. A 2013 global audit of climate change legislation stated that the United States' greenhouse gas emission reduction targets are "relatively modest when compared with other advanced economies." And "almost nowhere" else in the world, according to Bill McKibben in a recent Twitter chat with MSNBC's Chris Hayes, has there been the kind of political fracturing around climate change that we see in the United States.

To help Americans get the message, social scientists have one idea: talk about the scientific consensus not more, but more clearly. Starting in 2013, Maibach and his colleagues at GMU and the Yale Project on Climate Change Communication conducted a series of studies to test if, when presented with the data of scientific consensus, participants changed their mind about climate change. What they found was that in controlled experiments, exposure to a clear message conveying the extent of scientific consensus altered participants' estimate of the scientific consensus significantly. Other experimental studies have turned up similar results—a study conducted by Stephan Lewandowsky of the University of Bristol, for example, found that a clear consensus message made participants more likely to accept scientific facts about climate change. Frank Luntz, to the shock of veteran pundit watchers, was right: a clear scientific consensus does seem to change how people understand global warming.

Partially in response to Maibach's findings, the American Association for the Advancement of Science recently released their report "What We Know: The Reality, Risks and Response to Climate Change." The report, Maibach says, is "really the first effort...that attempted to specifically surface and illuminate the scientific consensus in very clear, simple terms." The report's first paragraph, in plain terms, notes that "virtually every national scientific academy and relevant major scientific organization" agrees about the risks of climate change. The New York Times' Justin Gillis described the report's language as "sharper, clearer and more accessible than perhaps anything the scientific community has put out to date."

And yet, the report wasn't universally heralded as the answer to climate change's communication problem—and it wasn't just under fire from conservatives. Brentin Mock, writing for Grist, wasn't sure the report would win climate scientists new support. "The question is not whether Americans know climate change is happening," he argued. "It’s about whether Americans can truly know this so long as the worst of it is only happening to 'certain other vulnerable' groups." Slate's Philip Plait also worried that the report was missing something important. "Facts don’t speak for themselves; they need advocates. And these advocates need to be passionate," he wrote. "You can put the facts up on a blackboard and lecture at folks, but that will be almost totally ineffective. That’s what many scientists have been doing for years and, well, here we are."

To some, the movement needs more a scientific consensus. It needs a human heart.

***

Matthew Nisbet has spent a lot of time thinking about how to talk about climate change. He's been studying climate change from a social science perspective since his graduate studies at Cornell University in the late 1990s and early 2000s and currently works as an associate professor at American University's School of Communications. And though he acknowledges the importance of a scientific consensus, he's not convinced it's the only way to get people thinking about climate change.

"If the goal is to increase a sense of urgency around climate change, and support an intensity of opinion for climate change being a lead policy issue, how do we make that happen?" he asks. "It’s not clear that affirming consensus would be a good long-term strategy for building concern."

Nisbet wanted to know if the context in which climate change is discussed could affect people's views about climate change: is the environmental narrative the most effective, or could there be another way to talk about climate change that might engage a wider audience? Along with Maibach and other climate change social scientists, Nisbet conducted a study that framed climate change in three ways: in a way that emphasized the traditional environmental context, in a way that emphasized the national security context and in a way that emphasized the public health context.

They thought that maybe placing the issue of climate change in the context of national security could help win over conservatives—but their results showed something different. When it came to changing the opinions of minorities and conservatives—the demographics most apathetic or hostile to climate change—public health made the biggest impact.

"For minorities, where unemployment might be 20 percent in some communities, they face everyday threats like crime. They face discrimination. Climate change is not going to be a top of mind risk to them," Nisbet explains. "But when you start saying that climate change is going to make things that they already suffer from worse, once you start talking about it that way, and the communicators are not environmentalists or scientists but public health officials and people in their own community, now you've got a story and a messenger that connects to who they are."

The public health angle has been a useful tool for environmentalist before—but it is especially effective when combined with tangible events that unequivocally demonstrate the dangers. When smog blanketed the industrial town of Donora, Pennsylvania in 1948 for five days, killing 20 people and rendering another 6,000 ill, America became acutely aware of the danger air pollution posed to public health. Events like this eventually spurred action on the Clear Air Act, which has played a large part in the reduction of six major air pollutants by 72 percent since its passage.

One voice that has begun focusing on the tangible impacts of climate change by showing its effects on everything from public health to agriculture is Showtime's new nine-part documentary series "Years of Living Dangerously." Eschewing images of Arctic ice and polar bears, the show tackles the human narrative head-on, following celebrity hosts as they explore the real-time effects of climate change, from conflict in Syria to drought in Texas. Over at the Guardian, John Abraham described the television series as "the biggest climate science communication endeavor in history."

But, as Alexis Sobel Fitts pointed out in her piece "Walking the public opinion tightrope," not all responses to the series have been positive. In a New York Times op-ed, representatives of the Breakthrough Institute, a bipartisan think tank committed to "modernizing environmentalism," argue that the show relies too heavily on scare tactics, which might ultimately harm its message. "There is every reason to believe that efforts to raise public concern about climate change by linking it to natural disasters will backfire," the op-ed states. "More than a decade’s worth of research suggests that fear-based appeals about climate change inspire denial, fatalism and polarization." "Years of Living Dangerously"'s reception, Fitts argues, reflects complex public opinion—for a subject as polarizing as climate change, you're never going to be able to please everyone.

Glaser agrees that the situation is complex, but feels that the media owes the public honesty, whether or not the truth can be deemed alarmist.

"I think the media probably should be alarmist. Maybe they haven’t been alarmist enough. It’s a tough balancing act, because if you present something to people and it’s a dire situation, and that’s the truth, they might just not want to accept it," he says. "That response, to say, 'This is just exaggerated,' is just another form of denial."

***

Climate change, some say, is like an ink blot test: everyone who looks at the problem sees something different, which means that everyone's answer to the problem will inherently be different, too. Some social scientists, like Nisbet, think that such a diversity of opinions can be a strength, helping create a vast array of solutions to tackle such a complicated issue.

"We need more media forums where a broad portfolio of technologies and strategies are discussed, as well as the science," Nisbet explains. "People need to feel efficacious about climate change—what can they do, in their everyday lives, to help climate change?"

Sol Hart, the Michigan professor, agrees that the current climate change narrative is incomplete. "From a persuasive perspective, you want to combine threat and efficacy information," he explains. "So often, the discussion is that there are very serious impacts on the horizon and action needs to be taken now, but there’s not much detail on action that could be taken."

Adding more context to stories might help round out the current narrative. "There’s such noise and chaos around a lot of big stories, and people just take these top-line items and don’t really dig deeper into what are the underlying issues. I think that’s been a big problem," Glaser explains. Slate has been doing explanatory journalism for years with its Explainer column, and other sites, like Vox and The Upshot (an offshoot of the New York Times) are beginning to follow a similar model, hoping to add context to news stories by breaking them down into their component parts. According to Glaser, that's reason for optimism. "I think news organizations do have a responsibility to frame things better," he says. "They should give more context and frame things so that people can understand what’s going on."

But Hayhoe thinks that we need more than just scientists or the media—we need to engage openly with one another.

"If you look at science communication [in Greek and Roman times] there were no scientific journals, it wasn’t really an elite field of correspondence between the top brains of the age. It was something that you discussed in the Forum, in the Agora, in the markets," she says. "That’s the way science used to be, and then science evolved into this Ivory Tower."

One organization that's trying to bring the conversation down from the Ivory Tower and into the lives of ordinary citizens is MIT's Climate CoLab, part of the university's Center for Collective Intelligence, which seeks to solve the world's most complex problems through crowdsourcing collective intelligence. Without even signing up for an account, visitors interested in all aspects of the climate change can browse a number of online proposals, written by people from all over the world, which seek to solve problems from energy supply to transportation. If a user wants to become more involved, they can create a profile and comment on proposals, or vote for them. Proposals—which can be submitted by anyone—go through various rounds of judging, both by CoLab users and expert judges. Winning proposals present their ideas in a conference at MIT, in front of experts and potential implementers.

"One of the things that's novel and unique about the Climate CoLab is the degree to which we're not just saying 'Here's what's happening,' or 'Here's how you should change your opinions,'" Thomas Malone, the CoLab's principal investigator, explains. "What we're doing in the Climate CoLab is saying, 'What can we do, as the world?' And you can help figure that out.'"

Climate change is a tragedy of the commons, meaning that it requires collective action that runs counter to individual desires. From a purely self-interested standpoint, it might not be in your best interest to give up red meat and stop flying on airplanes so that, say, all of Bangladesh can remain above sea level or southeast China doesn't completely dry out—that change requires empathy, selflessness and a long-term vision. That's not an easy way of thinking, and it runs counter to many Americans' strong sense of individualism. But by the time that every human on Earth suffers enough from the effects of rising temperatures that they can no longer ignore the problem, it will be too late.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)