The Crocodile Hunter’s Family Shares His Controversial Approach to Studying the Crocs

Steve Irwin’s wife and kids are feeding the debate over keeping animals in captivity

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/5f/495fba3b-4000-46d6-93b4-9cd3da4bcc3b/mar2015_j04_crocsirwin.jpg)

The saltwater crocodile is a great, stealthy, archaic beast that you wouldn’t expect to pacify with a little friendly tickle on the tail. But here is Daisy, a seven-foot Australian saltie on a grassy shore of the Wenlock River, as placid as a Pekingese. She’s being petted by 11-year-old Robert Irwin, who is stroking the lower third of her thrashing anatomy. Fortunately, a blindfold, gaffer tape and a rope muzzle ensure the amity of this relationship.

“It’s an honor and a privilege to work with the largest living reptile and largest terrestrial predator on the planet,” Robert tells me in the singsong tone of his television-ready family. “An awesome animal that roamed the primeval landscape for millions and millions of years.”

Daisy’s sawtooth tail whips the prone boy to the left. “The jaw pressure of the crocodile is incredible—3,000 pounds per square inch!”

Daisy’s tail whips him to the right. “I so admire the crocodile’s ability to kill with just its teeth. It’s quite amazing!”

Robert’s 16-year-old sister, Bindi, looks on solicitously. An actor, singer, game show host and, last year, a People cover girl, she’s confirming Daisy’s gender by inserting a finger into its cloaca and feeling around for genitalia. “It’s a girl!” she says. Her smile conveys a disarming buoyancy. “Here’s an animal that many people think is just a stupid, evil, ugly monster which kills people. That’s so not true!”

Bindi and Robert are the offspring of Steve Irwin, the boisterous, can-do naturalist of “Crocodile Hunter” fame. Perpetually clad in khaki shorts and hiking boots, the elder Irwin’s shtick—provocative, up-close interactions with wild animals and squeals of wonderment (“Crikey!”) at their magnificent deadliness—made him an international TV phenomenon. Irwin’s encounters with lethal animals ended in 2006, when a stingray’s barb pierced his heart while he was filming on the Great Barrier Reef. He was 44.

It’s late morning on the Wenlock and the odor of rotten meat hangs in the air. A feral pig carcass was used to bait the trap, one of 17 set along this 30-mile stretch of the river. The clean, bright sun has filtered a warm benediction down onto the bank, where Robert and Bindi; their mother, Terri; and a team of animal wranglers from the family-owned Australia Zoo are taking part in an extraordinary zoological study. For more than a decade researchers have monitored the behavior and physiology of saltwater crocs in Queensland, mainly at the Steve Irwin Wildlife Reserve, a 333,000-acre floral and faunal sanctuary on the Cape York Peninsula. The park was created by the Australian government as a living memorial.

What’s perhaps surprising is that Irwin, though controversial for his flamboyant hands-on approach to wildlife, quietly teamed with serious scientists and conservationists to make a genuine contribution to the systematic natural history of this enigmatic critter. Their discoveries about the salties’ habits, homing abilities and private lives have prompted a rethink of how they live and how we can coexist with them. Adult crocs have no natural predators except people, possibly because we’re meaner.

At a time when nature preserves are becoming more intensively managed, and zoos and aquariums are becoming more involved in field conservation, the line between “the field” and “animal holding facility” has blurred. By straddling both worlds, Irwin was smack in the middle of the quandary over the trade-off between protecting animals in the wild and studying them in captivity. Today, that quandary is further complicated by his family’s link to SeaWorld, harshly criticized since the 2013 documentary Blackfish for its treatment of killer whales and the subject of a withering new book by one of its former trainers.

The research project that Irwin helped launch is led by Craig Franklin, a University of Queensland zoologist, who, using capture techniques developed by the Croc Hunter, has trapped, tagged and released scores of salties in Aussie waterways. Data gathered by satellite and acoustic telemetry is beamed to a Brisbane lab, which maps the beasts’ whereabouts and logs their dive times and depths. The project is bankrolled by the Irwins’ zoo, federal grants and private donors—a little over $6,000 gets you the “exclusive naming rights” to a wild, caught croc.

Far from being just sedentary, solitary animals with one dominant male defending a set territory, as once thought, salties also turn out to be far-ranging creatures with complex social hierarchies. “Crocodiles are misunderstood because they’re not cute and fluffy,” says Bindi, a mainstay of Franklin’s annual field trips since Day 1.

When the blindfolded Daisy lets out a long, low growl, Bindi flashes a smile bright enough to illuminate the Sydney Opera House. “Crocodiles are very vocal, quite intelligent and so, so capable of love,” she says. “When an adult female rests her head on her mate’s stomach, there’s no way to describe it but love. They protect their babies and their homes and they have the most delightful sense of humor.” Then again, you may need to be a crocodile to fully appreciate its badinage.

There’s something inscrutable and prehistoric about the crocodile, as if it were designed by a committee of slightly ticked-off paleontologists. Its name derives from the Greek krokodeilos, meaning “worm of the stones.” Australian stone-worms lurk large in Dreamtime, the animist framework of Aboriginal mythology. The Gagudju people of Arnhem Land believe that Ginga, a spirit ancestor who helped create the rock formations of the region, underwent a transformation after accidentally catching fire. He dashed into the water to extinguish the flames and rough, lumpy scars formed on his back. He became the first crocodile.

Aboriginal people have traditionally hunted crocodiles for their meat, but the animal’s population remained stable until World War II ended and high-powered rifles became widely available. Commercial hunters and trigger-happy sportsmen slaughtered them indiscriminately. Since given protection in Australia during the early 1970s, their numbers have rebounded, then boomed to about 100,000.

Of the 23 crocodilian species, two inhabit the rivers, billabongs and mangrove swamps of the Australian tropics: the freshwater, or Johnson’s, crocodile, which is relatively harmless, and the formidable estuarine, or saltwater, croc, which can grow to 20 feet in length and weigh more than a ton. The range of the two overlaps somewhat, and sometimes the bigger and far more aggressive saltie will make a hearty lunch of the freshie.

Robert Irwin got it right: Salties are ruthlessly efficient killing machines. They come equipped with nearly 70 interlocking teeth, many as sharp as a steak knife. If one breaks off, there’s another underneath to replace it. Numerous muscles close the brute’s jaws but only a few open them.

Over the last 70 million years not much has changed in the saltie’s evolutionary design. This archosaurian behemoth can see well by day and by night and has three pairs of eyelids, one of which functions like swimming goggles to protect the croc’s vision underwater. Another membrane holds the tongue in place, preventing water from filling the lungs, which is why, even in contempt, the crocodile can’t stick it out.

Salties stalk their quarry with deadly patience—over days if necessary—learning its habits and feeding times. The croc skulks below the surface near the water’s edge, poised to ambush anything it can clamp those jaws on—cattle, wild boar, kangaroos, even other crocodiles as they come to drink. In a constant state of awareness, they’ll reveal themselves and strike only when confident of success.

Lunging and chomping, the saltie executes the death roll: Spun around by a corkscrew snap of the tail, the body twists and flips while the wrenching torque is absorbed at the powerful junction of head and neck. The disoriented victim is dragged into deeper water and drowned. Rather than swallow its meal immediately, the croc occasionally wedges what’s left under a rock or log to allow it to decompose, returning later to feed again. Croc rules where crocs rule: Keep your claws off my prey.

Not for nothing are salties called man-eaters. On average they attack and eat one a year in Australia. Last year they took three. Their sensitivity to human routine is downright unnerving. As Bill Bryson wrote in his down-under travelogue In a Sunburned Country: “The chronicles of crocodile killings are full of stories of people standing in a few inches of water or sitting on a bank or strolling along an ocean beach when suddenly the water splits and, before they can even cry out, much less enter into negotiations, they are carried away for leisurely devouring.”

The worst devouring was reported in 1945 during the Japanese retreat in the Battle of Ramree Island in the Bay of Bengal. British soldiers encircled swampland through which the Japanese were withdrawing. Nearly 1,000 soldiers are believed to have been munched to death by the resident salties.'

***********

Steve Irwin wrassled his first crocodile at the precocious age of 9. His father, a plumber who had opened a small reptile park on the Queensland coast, taught him to stalk salties at night and lug them out of the water. Together, they relocated crocs threatened by human settlements. In his 20s, Irwin worked as a trapper, removing problematic crocs from populated areas. He performed the service free on the proviso that—rather than the animals ending up as handbags and barbecue—he could keep them for the park.

Irwin took over the business in 1992, and that same year he married Terri Raines, a tourist and wildlife rehabilitator from Eugene, Oregon. Footage from their crocodile-trapping honeymoon became the first episode of “The Crocodile Hunter.”

As the show grew in popularity, Steve and Terri expanded the zoo, with more than 1,200 animals on 1,000 acres of bushland. The centerpiece was the Crocoseum, an amphitheater—inspired by the film Gladiator—in which audiences were regaled by a troupe of the all-singing, all-dancing “Crocmen.” Nowadays, crowds are entertained by Bindi and the Jungle Girls.

Passionate preservationists, Steve and Terri Irwin set up a foundation to protect habitats and wildlife, create rescue programs and finance scientific research into endangered species. They bought large tracts of land in Australia, hoping to turn them into protected areas, and campaigned against the illegal trade of ivory and exotic furs, and the culling of kangaroos by the Australian government.

Despite raising awareness for all manner of creatures great and small, Steve Irwin’s conservation legacy is decidedly mixed. His public image was dented in 2004 when he was filmed at the zoo entering the pen of a 13-foot saltie. In one hand was a dead chicken; in the other, cradled as tenderly as a six-pack of Fosters, the month-old Robert. Irwin’s antics inspired any number of tart and well-aimed comments. “For a second you didn’t know which one he meant to feed to the crocodile,” observed Germaine Greer, the Australian academic and writer. “If the crocodile had been less depressed it might have made the decision for him.”

Other critics drew comparisons to the moment when Michael Jackson dangled his infant son over a German hotel balcony. Children’s rights groups branded Irwin’s behavior as child abuse. The unrepentant Irwin claimed he had been “in complete control” and that the danger was perceived, not real. He was never charged with a crime.

Later that year it was alleged that, while making a documentary, he had broken laws banning interaction with Antarctic wildlife. (Irwin insisted he had merely been “bobbing around.”) An Australian environmental agency investigation recommended no action be taken against him.

Irwin’s death prompted an outpouring of grief from fans around the world. Amid the floods of tributes, Greer struck a discordant note by accusing him of tormenting animals and using them as a sideshow to his own showmanship. In an unforgiving Guardian essay, she wrote: “There was no habitat, no matter how fragile or finely balanced, that Irwin hesitated to barge into, trumpeting his wonder and amazement to the skies. There was not an animal he was not prepared to manhandle. Every creature he brandished at the camera was in distress.”

Back in 2003, Franklin, the zoologist, had no idea what to expect from Irwin when they met by chance in Queensland’s Lakefield National Park. “I was leery of the whole celebrity thing,” recalls Franklin, who had been recording the diving behavior of freshies. “You form impressions from the way the media portrayed Steve, and you wonder what this guy is really like, how knowledgeable he really is and how much of what he does is for the benefit of the camera.”

Franklin was pleasantly surprised. “We got along like a house on fire,” he says. “Despite having no formal training, Steve had all the qualities of a great scientist. His intellect was phenomenal, he was driven by curiosity and he had an endless list of questions that he sought answers to. Steve’s acute powers of observation proved invaluable in our crocodile tagging project.”

*********

The first tracking device implanted in a crocodile may have been the ticking clock swallowed by Captain Hook’s archnemesis. In J.M. Barrie’s 1911 novel Peter and Wendy, the pirate recounts a bit of swordplay with Peter Pan in which his right hand was sliced off and flung to a passing crocodile. “It liked my arm so much,” he laments, “that it followed me ever since, from sea to sea and from land to land, licking its lips for the rest of me.”

Hook relies on the ticking to alert him to the presence of the crocodile. In the end, the clock runs down and, unaware that the croc is nearby, the buccaneer meets his doom.

The shelf life of Franklin’s tracking units are considerably longer. Mounted to the concretelike nuchal shield of a saltie’s neck, his satellite transmitter records information for a year or more. To extend battery life, they’re programmed to turn on for 24 hours and then off for the next 72. “The technology lets us continually access data without disturbing the crocs or influencing their behavior,” Franklin says. “They act quite differently without human interference.”

Franklin is a tall, sturdy New Zealander, vigorous, dressed in denim, grizzled with neat graying whiskers. A great genial presence, with a jovial welcome. “I can’t count on my fingers the number of wild crocs in my homeland,” he says. “It’s zero.” He traces his interest in all things crocodilian to an ivory letter opener his father brought back from Egypt, where he fought during World War II. “The opener was in the shape of a croc,” Franklin recalls. “After Dad died, it was his only possession that I wanted.”

His zoological renown derives from the publication, in 2000, of a paper he co-wrote on the saltie’s four-chambered heart. Franklin and a University of Gothenburg colleague named Michael Axelsson discovered that the saltie has a unique set of valves in its right ventricle that acts as a shunt, diverting oxygen-poor blood away from the lungs and back into the bloodstream. “The heart valves of most vertebrates are passive and flaplike and function like saloon doors,” Franklin says. “The croc’s have cog teeth made of nodules of connective tissue. They look like interlocked human knuckles, and are actively controlled by the nervous system and open and close like elevator doors. It’s an absolute evolutionary novelty.”

If a crocodile needs to sink in a hurry, it can move its larger internal organs to the back of its body, like a submarine shifting ballast. Franklin and Axelsson proposed that the cogged-teeth valves allow crocs to ration oxygen underwater and stay submerged for hours.

In 2004, Franklin and Irwin joined forces with Australia’s parks and wildlife department to launch Crocs in Space, the first published satellite-tracking study of wild crocodiles. Dozens of adult salties were seized, restrained and outfitted with satellite transmitters to keep tabs on them.

Over the years, researchers have determined that saltwater crocs can hold their breath for nearly seven hours and dive to 23 feet; that they’re capable of walking miles overland between waterholes; that nesting mothers check out potential nests weeks before laying eggs; that dominant males maximize reproductive success, while subordinate males roam hundreds of miles of waterway, possibly in search of unguarded females.

“To me,” says Bindi, “their nomadic behavior is so, so fascinating.”

Salties, she notes, invest considerable parental care in the rearing of their young. The female digs them out of the nest when they start chirping and gently rolls the eggs in her mouth to assist hatching. Gingerly, if not tenderly, she carries her darlings to the water’s edge and remains at their side for several months. “Adorable!” Bindi says. What she loves most about the research study is that you can track a crocodile for ten years, and “learn all its secrets.” Some are caught and recaught and recaught again. “It’s kind of like seeing an old friend. You become attached to an individual and watch it grow and observe all its changes. It becomes part of your family. Imagine that: a dinosaur in your family! This is our purpose—catching prehistoric creatures and learning to share what we’ve learned with the world. And maybe, just maybe, someone listens and thinks, ‘Dinosaurs are extinct! These guys are so precious.’”

The name Bindi derives from the Aboriginal term for little girl. “It was also what my dad called one of his favorite crocodiles,” she says. Ebullient and almost frighteningly telegenic, Bindi was born in the global glare. Literally: Her birth was videotaped—and much of her childhood documented in feature films (Free Willy: Escape From Pirate’s Cove; Return to Nim’s Island) and TV nature shows (“Bindi, The Jungle Girl”; “Bindi’s Bootcamp”; “My Daddy the Crocodile Hunter”). By age 10 she had her own action figure, clothing line and kiddie fitness tape. “It’s been The Truman Show ever since I was knee-high to a grasshopper,” she says.

Today, a videographer and a still photographer are on hand to document the adventures of Bindi and her kid brother for the zoo’s website. While Robert hugs Daisy’s tail, Bindi rummages through Franklin’s surgical kit and pulls out scissors, sponge, scrub brush, syringe and anesthetic. She hands them to the professor, who cuts a tiny incision behind the croc’s left forelimb, inserts a transmitter and wires the wound shut. “The skin is so thick that stitching it together is like trying to sew up cowboy boots,” Bindi says. Franklin takes blood and tissue samples, and as he measures Daisy from tail to snout Bindi jots down the figures.

Like her father, Bindi seems to have an uncanny rapport with wildlife. And, like him, she seems to court controversy. Two years ago she wrote a 1,000-word essay on the environment for Hillary Clinton’s global e-journal but then withdrew it, publicly slamming the editors for deleting the edgier passages about the perils of overpopulation. Last year she was named a “youth ambassador” of SeaWorld, which donated $20,000 to the Irwin’s wildlife foundation for crocodile research. Animal rights activists slammed her for the alliance, which was announced shortly after the release of Blackfish, a film about the disquieting consequences of keeping killer whales at the company’s theme parks.

Blackfish proposes that keeping intelligent mammals in crippling confinement, making them endure violence from other captive whales and depriving them of food if they miss a cue or perform incorrectly is not only dangerous to SeaWorld trainers and audiences, but abusive and morally suspect. For her part, Bindi contends that SeaWorld and the Crocoseum, through public engagement, serve an invaluable educational purpose and provide experiences that build awareness and appreciation. “If we didn’t have animals in captivity, would we be inspired to save them?” she asks.

Told that court documents reveal SeaWorld has sedated whales to curb aggression, Bindi changes tack. “Look, when you’re working with an organization, nothing is perfect. So let’s step away from the bullying. In the end, we’re all trying to make a difference. We’re all trying to achieve goodness.”

*********

Herpetologists had long wondered how salties—notoriously poor long-distance swimmers—have inhabited so many South Pacific islands separated by wide expanses of ocean. But data gathered by Franklin and others revealed that during long voyages, the crocs ride surface currents, like surfers catching waves or migratory birds using thermal columns. In contrast, on jaunts of 6.2 miles or less the crocs under observation were just as likely to travel with or against the flow.

The migration patterns of three adult male salties—Ronald, Weldon and Banana-Head—were plotted after they were outfitted with transmitters and flown by helicopter to coastal spots far from their homes. All three returned to their original capture sites. Ronald journeyed some 60 miles over 15 days down the west coast of Cape York Peninsula. Weldon was transported from the west coast of the Cape York Peninsula to the east coast. After roaming through various river systems for three months, he navigated his way back through the Torres Strait and around the cape, covering more than 250 miles in 20 days. The strait is infamous for strong currents, and when Weldon reached the passage, the surface current was against him. So he stopped in a sheltered bay for three days before making his move. Banana-Head, who was released 32 miles south of where he was captured, swam up and down the coast for two weeks before making a beeline for his waterhole, which he reached in five days.

Salties’ uncanny ability to find their way home after being relocated, which Franklin and coworkers have documented in several studies, remains something of a mystery. Perhaps, Franklin speculates, “they swim around when released and realign themselves in their environment by celestial navigation or geomagnetic cues.”

Such findings proved significant because moving salties from one place to another, a practice known as translocation, has been used in Queensland to manage potential safety risks posed by the animals. “Our experiment showed that translocation was ineffective and extremely dangerous,” Franklin says. Residents and tourists got a false sense that the waters were crocodile-free. The government abandoned its program in 2011.

Though hunting salties is banned in Queensland, the state has established “Crocodile Management Zones.” Private contractors have been enlisted to capture, snare or harpoon rogue salties in those areas: “All crocodiles removed from the wild are placed in a zoo or crocodile farm or, in some cases, humanely euthanized,” according to the 2013 Hinchinbrook Shire Council Saltwater Crocodile Management Plan. Franklin says, “Some have regrettably died during their capture by the government, which is something that has never occurred during our research.”

Bindi considers the plan unconscionable. “Crocodiles are of vital importance,” she says. “They’re apex predators that regulate populations of other organisms. Without them, the entire ecosystem could collapse.” Sure, she concedes, crocodiles can, and sometimes do, attack and kill people. “But they’re not after people,” insists the Jungle Girl. When humans are attacked, she reasons, it’s almost always because they acted irresponsibly: fishing with bait tied to their belt, swimming after dark, ignoring warning signs or stealing them for souvenirs.

“It’s up to us to learn to live with crocs,” she says. “After all, they were here first.”

Related Reads

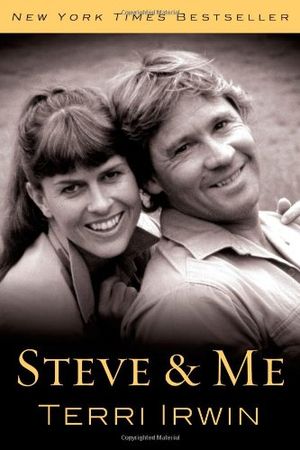

Steve & Me