The Hunt for Ebola

A CDC team races to Uganda just days after an outbreak of the killer virus to try to pinpoint exactly how it is transmitted to humans

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Hunt-for-Ebola-doctors-and-patient-631.jpg)

Shortly after dawn on a cool morning in late August, a three-member team from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, along with two colleagues, set out in a four-wheel-drive Toyota from a hotel in central Uganda. After a 15-minute drive, they parked on a dirt road in front of an abandoned brick house. Mist shrouded the lush, hilly landscape, and fields glistened with dew. “We checked this place yesterday,” said Megan Vodzak, a Bucknell University graduate student in biology who had been invited to join the CDC mission. “We were walking around and they flew out, and we’re hoping they will have moved back in.” A cluster of schoolchildren watched, rapt, from a banana grove across the road. The team put on blue surgical gowns, caps, black leather gloves and rubber boots. They covered their faces with respirators and plastic face shields. “Protection against bat poop,” Vodzak told me. Jonathan Towner, the team leader, a lanky 46-year-old with tousled black hair and a no-nonsense manner, peeked through a cobweb-draped door frame into the dark interior. Then they got to work.

Towner—as well as Luke Nyakarahuka, an epidemiologist from the Ugandan Ministry of Health, and Brian Bird and Brian Amman, scientists with the CDC—unrolled a “mist net,” a large hairnet-like apparatus fastened to two eight-foot-tall metal poles. They stretched it across the doorway, sealing off the entrance. Towner moved to the rear of the house. Then, with a cry of “Here we go,” he hurled rocks onto the corrugated-tin roof and against metal shutters, sending a dozen panicked bats, some of them possibly infected with Ebola, toward the doorway and into the trap.

The team had arrived here from Atlanta on August 8, eleven days after confirmation of an outbreak of the Ebola virus. They brought with them 13 trunks with biohazard suits, surgical gowns, toe tags, nets, respirators and other equipment. Their mission: to discover exactly how Ebola is transmitted to human beings.

Towner had chosen as his team’s base the Hotel Starlight in Karaguuza, in Kibaale district, a fertile and undeveloped pocket of Uganda, 120 miles west of the capital, Kampala. That’s where I met them, two weeks after their arrival. For the past 13 days, they had been trapping hundreds of common Ethiopian epauletted fruit bats (Epomophorus labiatus) in caves, trees and abandoned houses, and were reaching the end of their fieldwork. Towner suspected that the creatures harbored Ebola, and he was gathering as many specimens as he could. Based on his studies of Egyptian fruit bats, which carry another lethal pathogen, known as Marburg virus, Towner calculated that between 2 and 5 percent of the epauletted fruit bats were likely to be virus carriers. “We need to catch a fair number,” he told me, “to be able to find those few bats that are actively infected.”

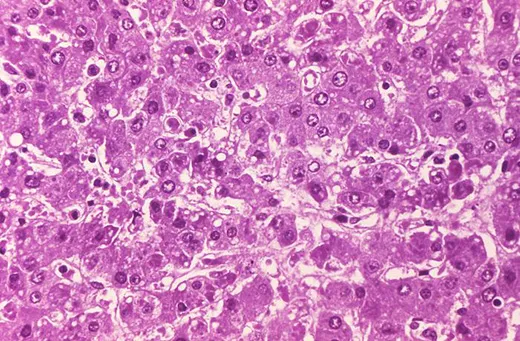

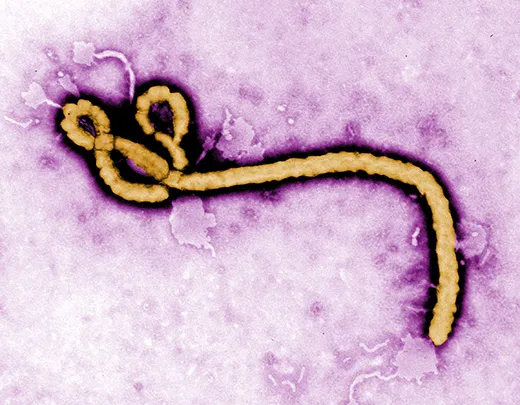

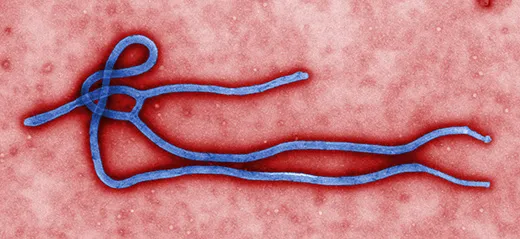

Ebola was first identified in Zaire (now Congo) in 1976, near the Congo River tributary that gave the virus its name. It has been terrifying and mystifying the world ever since. Ebola is incurable, of unknown origin and highly infectious, and the symptoms are not pretty. When Ebola invades a human being, it incubates for a period of seven to ten days on average, then explodes with catastrophic force. Infected cells begin producing massive amounts of cytokine, tiny protein molecules that are extensively used in intercellular communication. This overproduction of cytokine wreaks havoc on the immune system and disrupts the normal behavior of the liver, kidneys, respiratory system, skin and blood. In extreme cases, small clots form everywhere, a process known as disseminated intravascular coagulation, followed by hemorrhaging. Blood fills the intestines, the digestive tract and the bladder, spilling out of the nose, eyes and mouth. Death occurs within a week. The virus spreads through infected blood and other bodily fluids; the corpse of an Ebola victim remains “hot” for days, and direct contact with a dead body is one of the main paths of transmission.

In 1976, in a remote corner of Zaire, 318 people were infected by Ebola and 280 died before health officials managed to contain it. Nineteen years later, in Kikwit, Zaire, 254 people out of 315 infected perished of the same highly lethal strain. Four outbreaks have occurred in Uganda during the past 12 years. The worst appeared in the northern town of Gulu in the fall of 2000. More than 400 inhabitants were infected and 224 died from a strain of the virus called Ebola Sudan, which kills about 50 percent of those it infects. Seven years later, a new strain, Ebola Bundibugyo, killed 42 Ugandans in the district of that name.

A person stricken with Ebola wages a lonely, often agonizing battle for survival. “It becomes an arms race,” says the investigating team’s Brian Bird, veterinary medical officer and an expert in pathogens at the CDC. “The virus wants to make new copies of itself, and the human body wants to stop it from doing so. Most of the time, the virus wins.” The most lethal strain, Ebola Zaire, attacks every organ, including the skin, and kills between eight and nine of every ten people it infects. The virus strain, the amount of pathogen that enters the body, the resilience of the immune system—and pure luck—all determine whether a patient will live or die.

The virus arrived this time, as it usually does, by stealth. In mid-June 2012, a young woman named Winnie Mbabazi staggered into a health clinic in Nyanswiga, a farming village in Kibaale district. She complained of chills, a severe headache and a high fever. Nurses gave her antimalarial tablets and sent her home to rest. But her symptoms worsened, and two days later she returned to the clinic. Mbabazi died there overnight on June 21.

Two days after Mbabazi’s death, a dozen family members from a three-house compound in Nyanswiga attended her funeral. Many wept and caressed the corpse, following Ugandan custom, before it was lowered into the ground. Soon, most of them began to fall ill too. “Everybody was saying, ‘I have a fever,’” said one surviving family member. Five people from the compound died between July 1 and July 5, and four more during the next two weeks. One victim died at home, two expired at a local health clinic, two brothers died at the home of a local faith healer, and four died at the government hospital, in the nearby market town of Kagadi. The survivors “could not imagine what was killing their family members,” said Jose Tusuubira, a nurse at the facility. “They said, ‘It is witchcraft.’”

Health workers at Kagadi Hospital didn’t suspect anything unusual. “Malaria is the first thing you think of in Africa when people get sick,” says Jackson Amone, an epidemiologist and physician at the Ugandan health ministry in Kampala. “If you’re not responding to treatment, the [health workers] might be thinking that the problem is counterfeit medicine.” Then, on July 20, one of their own succumbed to high fever: Claire Muhumuza, 42, a nurse at Kagadi Hospital who had tended several members of the doomed family. Only then did the health ministry decide to take a closer look.

A few days later, a van containing samples of Muhumuza’s blood—triple-packaged inside plastic coolers—rolled through the guarded gate of the Uganda Virus Research Institute. A modest collection of stucco and brick buildings, it spreads across verdant lawns overlooking Lake Victoria in Entebbe. Founded as the Yellow Fever Research Institute by the Rockefeller Foundation in 1936, the UVRI has in recent years conducted scientific research on several other communicable diseases, including HIV/AIDS. Two years ago, the CDC opened a diagnostic laboratory at the institute for Ebola, Marburg and other viral bleeding fevers. (During previous outbreaks in Uganda, health officials had to send samples from suspected cases to laboratories in South Africa and the CDC.) A security fence is being constructed around the compound, where blood specimens brimming with Ebola virus and other deadly diseases are tested. The new layer of protection is a consequence of the U.S. government’s deepening concerns about bioterrorism.

Wearing biohazard suits, pathologists removed Muhumuza’s blood samples from their containers inside a containment laboratory. Fans vent air only after it has been HEPA-filtered. The researchers subjected the samples to a pair of tests to detect the presence of the virus and then detect antibodies in the blood. Every virus is made of genetic material enclosed in a protein coat or “shell.” A virus survives by entering a cell, replicating itself and infecting other cells. This process, repeated over and over, is fundamental for the pathogen’s survival. In the first test, scientists added a disruptive agent called a lysis buffer, which breaks down the virus and renders it harmless. Virologists then added a fluorescence-tagged enzyme to the now-denatured mixture, which helps identify strands of the virus’s ribonucleic acid (RNA). By heating, then cooling the mixture, scientists amplify a segment of the virus’s genetic material. They make multiple copies of a small piece of the genetic sequence, which makes it easier to see and study the virus’s genetic code, and thus identify it. The test identified the virus as Ebola Sudan.

The second test detects specific antibodies in the blood produced by cells in an attempt—usually futile—to beat back the Ebola virus. Droplets of blood, mixed with a reagent, were placed into little wells on plastic trays. When a colorless dye was added, the mixture turned a dark blue—a telltale sign of the presence of Ebola antibodies. On July 28, Ugandan health officials announced at a press conference and via the Internet that Uganda was facing its second outbreak of Ebola Sudan in two years.

At the time that epidemiologists confirmed the Ebola outbreak, health workers were tending about two dozen patients in the general ward at Kagadi Hospital. Several of these patients, including Claire Muhumuza’s infant daughter, and Muhumuza’s sister, were fighting high fevers and displayed other symptoms consistent with the virus. The administration called a staff meeting and urged the employees not to panic. “They told us what we were dealing with, that it is contagious, and they pleaded with us to stay,” says Pauline Namukisa, a nurse at the hospital. But the mere mention of the word “Ebola” was enough to spread terror through the ranks. Namukisa and nearly all her fellow nurses fled the hospital that afternoon; any patient who was mobile left as well. Days later, with the facility nearly abandoned, Jackson Amone, who had coordinated the response to Ebola outbreaks in Gulu in 2000, Bundibugyo in 2007 and Luwero in 2011, arrived to take charge of the crisis.

Amone, a tall, bespectacled physician with a baritone voice and an air of quiet authority, reached out to staff members who had fled and implemented a strict disinfection regimen to protect them from the contagion. He also asked a team from Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) in Barcelona, veterans in the Ebola wars, to assist in the treatment and containment of the outbreak.

After a decade, Ugandan health officials and MSF have developed the skills, manpower and resources to stop contagion quickly. The team set up a triage station and an isolation ward for suspected and confirmed Ebola cases, and applied supportive care—including rehydration, oxygen, intravenous feeding and antibiotics to treat secondary infections—to four people who had tested positive for Ebola. These treatments “keep patients alive for the immune system to recover,” I was told by one MSF doctor. “Intensive care can put the patient in a better condition to fight.”

The quick reaction by the health authorities may have prevented the outbreak from spiraling out of control. Health workers fanned out to villages and methodically tracked down everyone who had close contact with the family in which nine had died. Those showing Ebola-like symptoms were given blood tests, and, if they tested positive, were immediately isolated and given supportive treatment. Four hundred and seven people were ultimately identified as “contacts” of confirmed and suspected Ebola cases; all were monitored by surveillance teams for 21 days. The investigators also worked their way backward and identified the “index patient,” Winnie Mbabazi, although they were unable to solve the essential mystery: How had Mbabazi acquired the virus?

Jonathan Towner is the head of the virus host ecology section of the CDC’s Special Pathogens Branch. He specializes in the search for viral “reservoirs”—passive carriers of pathogenic organisms that occasionally leap into human beings. Towner earned his reputation investigating Marburg, a bleeding fever that can be 80 percent lethal in humans. The virus got its name from Marburg, Germany, where the first case appeared in 1967. Workers were accidentally exposed to tissues of infected African green monkeys at an industrial laboratory; 32 people became infected and seven died. Virologists eliminated the monkeys as the primary source of Marburg, because they, like humans, die quickly once exposed to the virus. “If the virus kills the host instantly, it’s not going to be able to perpetuate itself,” Towner explained, as we sat on the patio of the Hotel Starlight. “It has to adapt to its host environment, without killing the animal. Think of it as a process taking thousands of years, with the virus evolving along with the species.”

Between 1998 and 2000, a Marburg outbreak killed 128 workers at a gold mine in Congo. Seven years later, two more gold miners died at the Kitaka mine in Uganda. In 2008, a Dutch tourist who had visited a cave in Uganda became ill and died after returning to the Netherlands. Towner and other scientists captured hundreds of Egyptian fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) in the mines and found that many were riddled with Marburg. “Every time we’ve captured decent numbers of these bats, and looked for the virus, we’ve found it,” he says. A bat bite, contact with bat urine or feces, or contact with an infected monkey—which often acts as the “amplification host” in virus transmissions to humans—were all possible means of infection, says Towner.

Ebola is considered a “sister virus” to Marburg, both in the family of filoviridae that biologists believe have existed for millennia. They have similar genetic structures and cause nearly identical symptoms, including external bleeding in the most severe cases. “Marburg is one of the strongest arguments that bats are the reservoir for Ebola,” said Towner.

We were back at the Hotel Starlight in Karaguuza after spending the morning hunting for bats. The team had bagged more than 50 of them in two abandoned houses and was now preparing to dissect them in a makeshift screened-in lab beneath a tarp in the rear courtyard of the hotel. There, tucked out of sight so as not to disturb the other guests, the group set up an assembly line. Luke Nyakarahuka, the Ugandan health ministry epidemiologist, placed the bats one by one in a sealed plastic bag along with two tea strainers filled with isoflurane, a powerful anesthetic. The bats beat their wings for a few seconds, then stopped moving. It took about a minute to euthanize them. Then Nyakarahuka passed them on to other members of the team, who drew their blood, measured them, tagged them, plucked out their organs, and stored their carcasses and other material in liquid nitrogen for shipment to the CDC.

For Towner and the others, the hope is not only that they will find the Ebola virus, but also that they will shed light on how the pathogen is transmitted from bat to human. “If the kidneys are blazing hot, then the Ebola might be coming out in urine. If it’s the salivary glands, maybe it’s coming out in saliva,” I was told by the CDC’s Brian Amman. Testing of the Marburg virus carriers hasn’t indicated much, he says. “We’ve found the virus only in the liver and spleen, two body filters where you’d expect to find it.” Amman said that if research conclusively found that Ethiopian epauletted fruit bats carried Ebola, it might catalyze an HIV/AIDs-type awareness campaign aimed at minimizing contacts between bats and humans. It might also lead to the boarding up of the many abandoned and half-built houses in rural Africa that serve as bat roosting places and breeding grounds. “Some people here might say, ‘Let’s kill them all,’” said Amman. “But that would be destroying a valuable ecological resource. Our aim is to mitigate the interaction.”

None of the virus hunters had any expectation that a vaccine against Ebola was imminent. The drug development process takes an average of 15 years and costs billions of dollars. Pharmaceutical companies are reluctant to expend those resources to combat a virus that has killed about 1,080 people in 30 years or so. So far, nearly all Ebola vaccine research has been funded by the U.S. government to combat potential bioterrorist attacks. The Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases in Fort Detrick, Maryland, recently tested an experimental vaccine made from virus-like particles on guinea pigs and monkeys, and reported promising results. Several biodefense contractors have initiated small-scale safety trials with human volunteers, who are not exposed to the Ebola virus. But most virologists say that an effective vaccine is many years away.

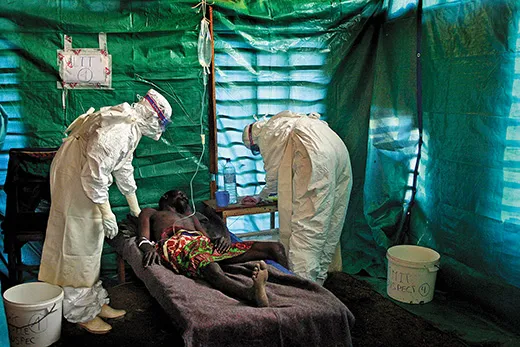

In late August, four weeks after Ebola was confirmed, I visited Kagadi Hospital, a tidy compound of tile- and tin-roofed one-story buildings on a hill overlooking the town. I dipped my shoes into a tub of disinfectant at the front gate. Posters on the walls of the administration building and the general wards listed symptoms of Ebola—“sudden onset of high fever...body rash, blood spots in the eyes, blood in the vomit...bleeding from the nose”—and instructed people to avoid eating monkey meat and to make certain to wrap the corpses of victims in infection-resistant polyethylene bags. Cordoned off by an orange plastic fence in the rear courtyard was the “high-risk” ward, where Ebola patients are kept in isolation and attended by masked, gloved, biohazard-suited health workers. “If you were on the other side of the orange tape, you would have to be wearing an astronaut suit,” a physician from Doctors Without Borders told me.

Inside the tent, two women were fighting for life. One had been a friend of Claire Muhumuza, the nurse; after Muhumuza died on July 20, she had cared for Muhumuza’s baby daughter. Then on August 1, the little girl succumbed. On August 3, the caretaker fell ill. “Three days ago I went in and called her name, and she responded,” Amone said. But today, she had fallen unconscious, and Amone feared that she would not recover.

The next afternoon, when I returned to the hospital, I learned that the caretaker had died. The way Amone described it, she had lost all sensation in her lower limbs. Her ears began to discharge pus, and she fell into a coma before expiring. The bereaved family was demanding compensation from the hospital, and had threatened a nurse who had apparently encouraged her to take care of the infected baby. “It has become a police case,” Amone told me. One last Ebola patient—another health worker—remained in the isolation ward. “But this one is gaining strength now, and she will recover,” Amone said.

Now, after 24 confirmed cases and 17 deaths, the latest flare-up of Ebola appeared to have run its course. Since August 3, when the caretaker had been diagnosed, 21 days had passed without another case, and the CDC was about to declare an official end to the outbreak. (By mid-September, however, Ebola would erupt in Congo, with more than 30 reported deaths, and more than 100 individuals being monitored, as this article went to press.)

After visiting Kagadi Hospital, I joined three nurses from the health ministry, Pauline Namukisa, Aidah Chance and Jose Tusuubira, on a field trip to visit the survivors from the family of Winnie Mbabazi—Patient Zero. The three nurses had spent much of the past three weeks traveling around the district, trying to deal with the societal fallout from the Ebola outbreak. Healthy family members of people who had died of Ebola had lost jobs and been shunned. Those who had come down with fevers were facing even greater stigma—even if they had tested negative for the virus. They were banned from public water pumps, called names such as “Ebola” and told to move elsewhere. “We have to follow up, to sensitize people again and again, until they are satisfied,” Tusuubira told me.

The rolling hills spilled over with acacias, jackfruit, maize, bananas and mango trees. We drove past dusty trading centers, then turned onto a dirt path hemmed in by elephant grass. After a few minutes we arrived in a clearing with three mud-brick houses. Except for a few chickens squawking in the dirt, the place was quiet.

A gaunt woman in her 60s, wearing an orange-and-yellow checkered headscarf and a blue smock, emerged from her hut to greet us. She was the widow of the family patriarch here, who had died in late July. One of four survivors in a family of 13, she had been left alone with her 26-year-old daughter and two small grandchildren. She led us to a clearing in the maize fields, where earthen mounds marked the graves of the nine who had succumbed to Ebola.

The woman displayed little emotion, but was clearly terrified and bewildered by the tragedy that had engulfed her. Shortly after the Ebola outbreak was confirmed, she told us, CDC and health ministry officials wearing biohazard suits had shown up in the compound, sprayed everything with disinfectant “and burned our belongings.” But she still wasn’t convinced that her family had died of the virus. Why had some perished and others been spared, she demanded to know. Why had she tested negative? “We have explained it to her thoroughly, but she doesn’t accept it,” Tusuubira said, as we walked back from the cemetery to the car. “Even now she suspects that it was witchcraft.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)