The Seahorse’s Odd Shape Makes It a Weapon of Stealth

The shape of the seahorse’s snout and its painfully slow movements create help create minimal water disturbance, increasing its odds of bagging prey

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20131126101141seahorse-small.jpg)

Seahorses belong to the genus Hippocampus, which gets its name from the Greek words for “horse” and “sea monster.” With their extreme snouts, weirdly coiled bodies and sluggish movements produced by to two puny little fins, these oddly shaped fish seem like an example of evolution gone terribly awry. And yet, new research published today in Nature Communications shows that it is precisely the seahorse’s uncanny looks and slow motions that allow it to act as one of the most stealthy predators under the sea.

Seahorses, like their close relatives the pipefish and sea dragons, sustain themselves by feasting on elusive, spastic little crustaceans called copepods. To do this, they use a method called pivot feeding: they sneak up on a copepod and then rapidly strike before the animal can escape, much like a person wielding a bug swatter tries to do to take out an irritating but otherwise impossible-to-catch fly. But like that lumbering human, the seahorse will only be successful if it is able to get near enough to its prey to strike at very close range. In the water, however, this is an even greater feat than on land because creatures like copepods are extremely sensitive to any slight hydrodynamic change in the currents around them.

A seahorse stalking prey. Photo by Brad Gemmell

So how do those ungainly little guys manage to feed themselves? As it turns out, the seahorse is a more sophisticated predator than appearance might suggest. In fact, it is precisely its looks that make it an ace in the stealth department. To arrive at this surprising conclusion, researchers from the University of Texas at Austin and the University of Minnesota used holographic and particle image velocimetry–fancy ways of visualizing 3D movements and water flow, respectively–to monitor the hunting patterns of dwarf seahorses in the lab.

In dozens of trials, they found that 84 percent of the seahorses’ approaches successfully managed not to sound the copepod’s retreat alarms. The closer the seahorse could get to its unsuspecting prey and the faster it struck, the greater its odds of success, they observed. Once in range of the copepod, seahorses managed to capture those crustaceans 94 percent of the time. Here, you can see that method of attack, in which the seahorse’s giant head looks like a floating bit of marine sludge drifting toward the blissfully ignorant copepod:

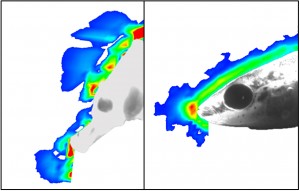

A seahorse (left) produces significantly less water disturbance, shown here as warmer colors, compared to a traditional fish like the stickleback (right), making it a slow but highly effective predator. Photo by Brad Gemmell

The way the seahorse’s movements and morphology–especially its head–interact with the water particles, the researchers found, likely take the credit for its exceptional hunting skill. The animal’s arched neck acts like a spring for generating an explosive strike, they describe, while the shape of its snout–a thin tube with the mouth positioned at the very end–allows it to drift through the water while creating minimal disturbance.

To emphasize this pinnacle of engineering, the team compared water disruptions caused by seahorses with those of sticklebacks, a relative of the seahorse but with a more traditional fishy look. Thanks to the shape and contours of the seahorse’s head, that predator produced significantly less fluid deformation in the surrounding water than the stickleback. The poor stickleback possesses neither the morphology nor posture to generate “a hydrodynamically quiet zone where strikes occur,” the authors describe. In other words, while the seahorse may appear a bit odd so far as fishes go, evolution was obviously looking out for that funny but deadly animal’s best interests.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)