On the Trail of Florida’s Bigfoot—the Skunk Ape

Is an imaginary creature a case of mistaken identity?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c6/cc/c6cc4ff1-75be-42c0-a930-c63e8ba6e54b/img_7147.jpg)

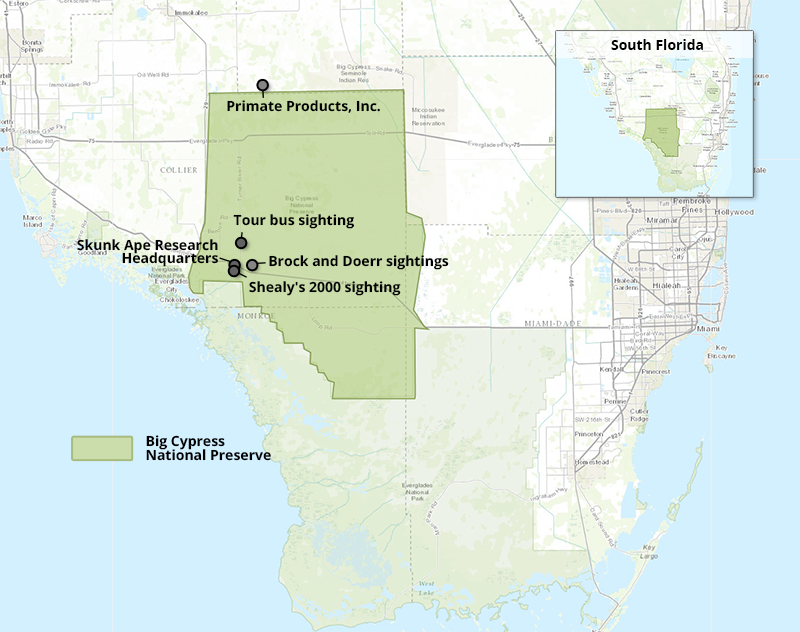

The first time Dave Shealy saw a skunk ape, he says, he was ten years old. It was 1974, a few years after his father had come upon a set of footprints left by the creature—an Everglades version of Bigfoot named for its supposedly pungent odor. Dave was out deer hunting with his older brother, Jack, in the swamp behind his house, in what’s now Big Cypress National Preserve, when he encountered the ape incarnate.

“It was walking across the swamp, and my brother spotted it first. But I couldn’t see it over the grass—I wasn’t tall enough,” Shealy says. “My brother picked me up, and I saw it, about 100 yards away. We were just kids, but we’d heard about it, and knew for sure what we were looking at. It looked like a man, but completely covered with hair.”

He and his brother stared at the creature, mouths agape, but almost at the same time, as he tells it, the skies opened and rain poured down. The ape hurried away, into the cypress hummocks scattered amongst the marsh. “Holy crap,” he remembers thinking. “I finally saw this damn thing, and it got away, just like that.”

But the fleeting moment left an indelible impression on young Shealy, who’s now 50 years old. In the decades since, he’s relentlessly pursued skunk apes and seen them, he says, on three other occasions. He’s written a field guide, made TV appearances, continually investigated reported sightings and established a Skunk Ape Research Headquarters on his property, where tourists can learn all about the legendary creature. He bills himself as the Jane Goodall of skunk apes. “I am the expert,” he told a Bigfoot website last year, “the state and county expert on the Florida skunk ape, and have been for years.”

In July 2000, he captured one of his encounters on video. In the grainy daytime footage, shot from hundreds of feet away, the creature spends a minute or so moseying around in a hummock of palm trees. Then, shortly after it begins striding across the open swamp (at about 1:48 in the video below), it breaks into a long-limbed run—as though suddenly aware it’s being watched—escaping into a grove of palm trees.

Shealy notes that, at the time, the swamp was covered by over a foot of water, making the animal’s speed (which he estimates to be 22 miles per hour) impossible for any human to achieve. But it’s extremely hard to watch this video and see anything but a guy in a gorilla suit, hurrying across the swamp:

This impression is especially concerning because, according to any respected biologist, the skunk ape does not exist. “People report seeing this mythical creature from time to time,” says Bob DeGross, a public affairs officer with the preserve. “But there has never been a substantiated sighting of the skunk ape that was verified by National Park Service wildlife staff.” Critics point out that, despite the dozens of unrelated ongoing research projects conducted in the Everglades that use motion-activated trail cameras, no one has ever captured indisputable proof of the skunk ape or come upon the remains of one. “The empirical evidence is extremely weak,” says Sharon Hill, a researcher and columnist for the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry who’s written about Bigfoot, the skunk ape and other mythical creatures. “It’s almost entirely eyewitness testimony, which is the most unreliable evidence you can have.”

Shealy responds by observing that things decompose quickly in the swamp, and that, at 2.2 million acres, it’s the largest area of protected land east of the Mississippi, most of it rarely visited (both true). It’s easy to imagine, he argues, that a handful of reclusive animals could live in it essentially unnoticed and leave virtually no evidence. “I know what I’ve seen,” he says. “For someone who hasn’t come here and put in the time to say otherwise doesn’t really matter to me.”

To a curious observer, all this prompts an important question. Is Shealy a visionary biologist, a mistaken eyewitness, or an enterprising fraud?

* * *

Earlier this year, to try answering this question, I made the trip to Shealy’s property in Ochopee, Florida, an hour’s drive into the Everglades from the west. A few minutes after I arrived, Shealy met me at the research headquarters (which also serves as a gift shop that sells skunk ape T-shirts and shot glasses, a campground, a base for Shealy’s staff of five to give swamp buggy and airboat tours, and a home for his menagerie of ten-foot-long pythons and talking parrots).

“I was out hunting frogs until 4:30 a.m. last night,” he told me, “and I’ve got a whole pile of them that need skinning. Want to help?” A tall, bearded man, Shealy stared at me with an intense gaze, as though waiting for me to freak out, then began to chuckle, saying he was joking, and would be skinning them all himself. After retrieving a sackful of wriggling frogs from the fridge inside his house behind the gift shop, he sat down on his deck, began hacking them apart and started telling me about the skunk ape’s long history.

“Local Native American groups from around here, the Seminoles and the Miccosukee tribe, they’ve known and told stories about the skunk ape for centuries,” he said. Over the past 60 years or so, Floridians of all stripes began reporting that they were seeing the creature. (A similar pattern happened in the Pacific Northwest, where indigenous beliefs in the Sasquatch eventually led to the skunk ape’s better-known cousin, Bigfoot.)

In one of the earliest well-publicized sightings, a pair of hunters claimed the ape invaded their camp in 1957. It’s unclear who coined the name skunk ape, but it appears to have surfaced sometime during the '60s. During the 1960s and '70s, the period when Shealy had his first sighting, more and more reports trickled in, as far north as the Florida panhandle, but most often in the Everglades. The skunk ape eventually attracted mainstream attention, including a bill introduced (but not passed) in the Florida legislature in 1977 that would have made it illegal to “take, possess, harm or molest anthropoid or humanoid animals.” It was around this time that Shealy, a teenager, spotted evidence of the creature for the second time, in the form of enormous four-toed footprints left at night near his hunting camp deep in the Big Cypress interior.

Occasional sightings continued for years, and the skunk ape hit the news again in 1997, when passengers on a tour bus traveling through the preserve claimed they spotted the animal. “This was 30, 40 people, all saying they saw the same thing,” Shealy says, “a seven-foot, red-haired ape.” After decades of idle interest in the creature, he decided to get serious about finding it, baiting the area with lima beans (the story goes that the omnivorous apes loved the legume). He repeatedly found the beans missing in the morning, along with tracks left in the night. Then, just two miles away, a pair of local residents—Jan Brock, a real estate agent, and Vince Doerr, chief of the Ochopee Fire Control District—separately spotted a large, hairy biped minutes apart while driving through the preserve one morning in July. “The thing just ran in front of my car,” Brock told me when I called her after my visit. “It was shaggy-looking, and very tall, maybe six-and-a-half or seven feet tall.” Doerr, who told me that he’d never believed in the skunk ape before seeing it cross the road about a half mile in front of his car, snapped a photo of it just before it vanished into the swamp.

“I’m going to spend the next six months looking for this thing,” Shealy remembers vowing at the time. “I’m not going to do anything else. Every day I’m going to get up and go looking and keep doing this until I see it.”

Shealy set up a few tree stands on his 30-acre property, and spent the next year sitting in them, baiting the area and watching for the skunk ape, or trekking across the Everglades, trying to find the creature’s trail. Finally, on September 8, 1998, he says, he was rewarded with his second sighting. Perched in a tree and half asleep, “I heard something splashing in the water: splash, splash, splash,” he told me. “At first, I thought it was a person, but then from around 100 yards away, I saw it coming toward me. It was a skunk ape, the same as I saw when I was a kid.” As it walked by, unaware of being observed, he shot several photos of it, watching it disappear into the nearby tree hummock. Later, he returned and made a concrete cast of its footprint, which still sits in the gift shop.

After he finished skinning the frogs, Shealy fried me a few pairs of legs for lunch and told me about his two most recent sightings: Once in 2000, when he filmed the video clip, and the latest in August 2011, when he was picking saw palmetto berries in the swamp and was startled by an unforgettable odor. “Right away, I could smell it—kind of like a wet dog and a skunk, mixed together,” he said. It emerged from behind a palm frond, spotted Shealy and bolted, leaving no evidence.

He still searches for the skunk ape, concentrating his work mostly in March and April—when the dried-out swampland allows for easier hiking and preserves tracks better—and investigating the dozen or so sightings that are called in to him annually. He’s boiled his findings down into a field guide, available for $4.95 at his gift shop (the skunk apes stand six to seven feet tall, spend about half their lives in the trees, and might pick up their awful odor from their time in underground alligator caves, it says), and mapped the most recent sightings. He was even filmed for an episode of “Finding Bigfoot,” the Animal Planet reality show, although he was infuriated when the producers balked at the logistical difficulties of traveling into the swamp to investigate a sighting and asked him to “fake it” in his backyard instead.

Of course, many people question Shealy's authenticity—something that weighed upon me as I ate the lunch he’d made for me and politely listened to his claims. Apart from the sheer unlikeliness of the skunk ape’s existence, critics point out that Shealy openly profits from the supposed animal, selling tchochkes and offering swamp tours. In 2000, he even applied for a grant from the Collier County Tourism Development Council to fund his research, and some remarked upon the conveniently timed release of his skunk ape footage shortly before the hearing, along with the dubious creature in the video. “The skunk ape, which bears a striking resemblance to a guy in a monkey suit, was filmed walking across a clearing,” Naples Daily News columnist Brent Batten wrote at the time. “Anyone who previously doubted the existence of the skunk ape should now be converted. The same way that anyone who doubted the existence of flying saucers carrying evil space aliens would have a change of heart after seeing Plan Nine from Outer Space.”

* * *

The belief in mythological animals might be as old as humanity itself. Nearly every culture’s folklore contains at least one imagined creature in its folklore that has no place in modern science. You’ve likely heard of the Loch Ness Monster and Bigfoot, but there are thousands of others. In the Philippines, people have long feared a vampire-like animal called the Aswang. British folklore prominently features supernatural black dogs associated with death that roam the countryside. Other places have aquatic monsters, enormous worms or massive, lizard-like demons.

It’s easy to imagine how, in the days when much of the planet had yet to be explored and catalogued, you might have reasonably believed in the existence of any of these beasts. But in the present day, when every square mile of the earth’s surface has been photographed by satellites, and scientists have identified 1.3 million species (with mostly plants, tiny animals and microbes remaining to be found), how could you still believe in a lumbering, seven-foot-tall ape, hiding out in one of the most well-studied countries on the planet?

“In the context of the modern world, where truth is provided by the consensus of mainstream science and medicine, I think many people feel disempowered,” says Peter Dendle, a professor at Penn State University who’s written extensively about folklore and cryptozoology (the search for cryptids, animals that aren’t recognized by the scientific community). “I think cryptozoology serves as a means of staking a line, and saying, 'You scientists don't know everything. There are still truths out there to be discovered.'” Cryptid enthusiasts, he’s found, are disproportionately male and often share a number of outsider traits that I couldn’t help but see in Shealy: a distaste for authority, a rugged connection with the outdoors and a hearty sense of individualism and self-reliance.

Psychologists, meanwhile, have observed an overlap in people who believe in cryptids and those who suffer from psychological conditions including ADHD, depression and even dissociation. These underlying disorders, it’s speculated, increase the chance that people will incorrectly interpret an otherwise explicable real-world experience. In other words, a psychologically stressed or unstable person might catch a brief glimpse of a deer or bear far away in the woods and become certain it’s a bipedal hominid heretofore undiscovered by science.

On an individual level, it’s easy to see how a one-time mistake like this could persist. “These people invest time, effort and money into this activity, which they’re passionate about,” Sharon Hill, the skeptic, told me. “They have a sense that they’re doing something with a higher purpose. Maybe they’ll be the one to finally solve the mystery, and they’ll become famous and respected—something that they might not have in their life otherwise.” This sort of belief is self-reinforcing: Admitting that a cryptid is nonexistent would mean giving up the years they’ve devoted to the search thus far. The only option is to keep looking, certain that indisputable proof is just around the corner.

Any of these explanations should imply that, when I followed Shealy into the muddy swamp after lunch—to the spot where he’d spotted the skunk ape in 2000—I shouldn’t have had even the slightest expectation that we’d see one in the flesh. But as we walked along the meandering trail, listening to the drone of insects and the squawking of birds overhead, part of me held a faint hope that he wasn’t crazy or self-delusional, that he really had seen the creature and that there was a tiny chance we would too. “In this digital age, the world suddenly feels very, very small,” Dendle, the folklore expert, told me. “There’s a sense of claustrophobia, and a loss of wonder. Cryptozoology is a way of refusing to have the last piece of the unknown taken away—of imagining there’s something bigger than us out there.”

There aren’t many rational reasons to believe the skunk ape might be real, but after doing some digging, I was able to find exactly one: The line between real animals and cryptids, it turns out, is much messier than you might imagine. Carl Linnaeus’ 1735 landmark text of modern biology Systema Naturae listed the pelican, antelope and narwhal as cryptids. As recently as the start of the 20th century, the Komodo dragon, the giant squid and the okapi were thought to be cryptids, before the Western scientific establishment changed its mind in the face of indisputable evidence: the animals' dead bodies.

This still goes on. Dozens of new mammal species have been discovered since the start of the 21st century, although they’re generally less extraordinary cases, often the result of subtle taxonomic changes. Perhaps the most well-known of these is the olinguito—the first new carnivore discovered in the Americas in 35 years—which was announced in August 2013. The small, arboreal animal had eluded the scientific community for all of modern history, confused for its close cousin, the olingo. That the olinguito was overlooked is all the more remarkable because thousands of the animals live in the cloud forests of Colombia, dozens of their skulls and furs have been preserved in museum collections, and one individual olinguito actually lived in the Smithsonian’s National Zoo for a few years in the 1960s.

“I think that there’s just a lot out there that most people don’t know about, that we really don’t understand about the world,” Shealy told me as I followed him down an overgrown path into the swamp at the rear of his property. I couldn’t help but recall what Kristofer Helgen, the National Museum of Natural History zoologist who discovered the olingutio, told me just before the press conference announcing it. “The discovery of the olinguito shows us that the world is not yet completely explored, its most basic secrets not yet revealed.”

Some Bigfoot believers argue that the creatures could be a tiny relict population of an ape species thought to have gone extinct millions of years ago, such as Gigantopithecus or Paranthropus. If so, it certainly wouldn’t be the first species to be resurrected. One, the Chacoan peccary—a wild pig-like mammal native to South America—was initially known only from fossils found during the 1930s. Then, in 1971, scientists realized thousands of the animals were alive and well in the Chaco region of Argentina. During the intervening decades, biologists had been certain that the peccary was long extinct. Local residents, meanwhile, were aware of the animal’s existence the entire time.

* * *

Shealy and I spent about an hour hiking the swamp before climbing up into one of his tree stands to take a break. We talked about Shealy’s life in the swamp and his family’s history there, which dates to 1891, when they settled and built the area’s first schoolhouse. For decades, they catered to tourists, giving swamp tours and renting spots on their campground. After the NPS established the preserve in 1974, though, it bought out most of his neighbors, and things took a turn for the worse. “The park took all our air buggy trails, and swamp boat trails, and they built their own campground. They stole our 50-year customer base,” he said. “My mom and dad worked hard for this place, and then the government built six campgrounds and instructed their employees to tell people not to come here. They just wanted us gone.” Most infuriating, he said, was that if he wanted to keep giving visitors tours on swamp property, he’d have to sit down in a classroom and take an official test. His burning resentment of the park service was palpable. (Later, when I asked Bob DeGross, the park spokesman, about all this, he declined to comment on Shealy’s particular complaints, but acknowledged that the creation of the preserve was “a controversial process.”)

Then Shealy returned to talking about the skunk ape; he pointed out plants growing in the surrounding area that he believes the family of 6 to 12 existing animals feed on and complained that most park authorities who have declared that the animal don't exist hadn’t spent nearly as much time as him in the swamp. But at a certain point, it became hard to ignore the fact that his long-running feud with the government endowed some of his claims regarding the skunk ape with the tinge of conspiracy. He told me that the night after he spotted the skunk ape in 1998, he saw a government helicopter hovering above the site for hours on end. He said that when he spotted the animal in 2011, he gathered a small sample of its hair off a branch where it’d been snagged, but that unidentified federal agents came to his house the next day and confiscated it.

As I listened to Shealy’s claims, they also became hard for me to swallow for a reason that had nothing to do with his history: his utter lack of hard proof. “There’s something called the International Code of Nomenclature, and it tells you that if you’re going to describe a new species, there are certain types of evidence that you have to have, and they have to be available for other scientists to evaluate,” Roland Kays, a wildlife zoologist who worked with Helgen in discovering the olinguito, had told me before my trip to Florida. “That’s where sightings are just useless. The quality of the evidence needs to stand up to the boldness of the claim.”

While it’s impossible to completely disprove the possibility, he said, it seems exceedingly unlikely that the skunk ape could live for centuries in south Florida without us coming upon firmer evidence: a specimen, likely in the form of roadkill. Kays pointed me to the case of the eastern cougar—a relict population of cougars that, some believe, lives in the Northeast, although we have no verifiable evidence. The unlikelihood of that scenario was demonstrated in 2011, when an actual cougar, for unclear reasons, migrated from South Dakota to New England and produced several pieces of hard evidence along the way, including clear photos taken by motion-activated trail cameras and, eventually, its dead body, hit by an SUV on a highly trafficked Connecticut parkway.

Moreover, the ecological and evolutionary circumstances of the skunk ape are suspect. There’s no fossil evidence showing that the extinct mega-apes that some Bigfoot believers cite ever lived anywhere in the Americas. North America, meanwhile, has never proved itself as a hospitable ecosystem for any great ape apart from humans.

The lack of evidence may tell us that the skunk ape doesn’t exist. But does that make Shealy a fraud? Many have observed that the animal in these images looks remarkably like a person in disguise, and have even speculated that it’s Shealy’s media-averse brother, Jack—the only other person present at Dave’s very first sighting—wearing the costume.

Sitting up there in that tree stand and chatting with Shealy, I wanted to come to any possible conclusion besides one that would result in my traveling to the swamps of Florida to spend a day with a generous, likable man, listen to his stories and then call him a liar. As our conversation concluded, we hiked back to his house, and he gave me a can of Coke before I set off. “Drive safe now,” he said, shaking my hand before I turned to get in my car.

* * *

Shealy had told me about one time, when a skunk ape sighting was called in to him from the nearby town of Immokalee and he went to investigate. He followed a pair of tracks until they came up against something unexpected: a tall, barbed-wire fence that enclosed a mysterious primate-breeding facility. He stood there, listening to the whooping cries of monkeys, before following the tracks as they continued away. The skunk ape, he speculated, had been attracted by the cries of its distant brethren. He’d previously heard rumors of the place, and even believed that its location might not be coincidental, given the presence of a large ape indigenous to the surrounding area.

The story sounded as far-fetched to me as any he’d told. But, undaunted, I pulled over at the Big Cypress welcome center about three miles from his house and searched “primate facility Immokalee” on my phone. Primate Products, Incorporated was the first hit. Immokalee, it turns out, is home to a facility that breeds several species of macaque monkeys—with a total capacity of about 1,500—and has been the subject of frequent animal rights protests. I was even able to find the facility’s coordinates and spot it on Google Maps. With a full tank of gas and a few hours of sunlight left, I decided, on a whim, to drive 45 miles north to see what I’d find there.

After about half an hour on a state highway, I turned off onto sandy, backcountry roads that put a beating on my subcompact rental car. After passing a state prison and tomato fields, the landscape emptied into sand-clogged scrub. I drove as fast as I could, battling a strange paranoia that was inexplicably setting in. I was driving an incongruous car, with no explanation why I should be there, and couldn’t shake the sense I was being watched, a feeling that was heightened when a pickup appeared seemingly from nowhere and began following me closely. I slowed down, and felt a bit of relief as the truck passed, but knew something was amiss. I wasn’t about to discover the secret of the skunk ape, but it seemed that I was about to discover something weird.

That’s when I arrived at a huge sign hammered into two-by-fours set in fresh concrete. “WARNING! PRIVATE PROPERTY,” it read. “If you are employed by a Local, State, or U.S. Government agency or are a curious individual you must have prior permission to enter this property.” Even those with clearance, it warned, had to proceed directly to their job site: “Permission to enter is not permission for sight-seeing or ‘looking around.’”

After a few minutes of deliberation, I decided that my curiosity didn’t justify getting arrested inside a monkey-breeding facility deep in Florida’s backcountry. But as I drove off, I mulled over a new possibility. Was it so far-fetched to think that the whole thing might be a case of mistaken identity, and the skunk ape was actually an escaped primate?

Primate Products isn’t the only primate-breeding center in the area. A research organization called the Mannheimer Foundation runs a satellite facility about an hour north of Immokalee that houses a reported 5,000 macaques and baboons, and in July 2013, an unidentified company released plans to build a new 3,000-primate compound nearby. “Obviously the weather has a lot to do with it,” Primate Products’ president Thomas J. Rowell told the local News-Press. “The mild winters make for ideal climate to breed and maintain non-human primates in a setting that is very close to their natural habitats.”

Could a resident primate actually escape and survive in the wild? Primate Products declined to comment on any escapes for this article, but Bob DeGross, the preserve public affairs officer, told me he’s seen escaped primates in Big Cypress several times, likely the result of people releasing unwanted exotic pets into the wild, and in one case, the damage wrought by Hurricane Andrew to breeding facilities in Miami in 1992. Meanwhile, there are several confirmed wild, self-sustaining monkey populations statewide, including one in Naples (about a 45-minute drive west of Shealy’s property) and a larger group in Silver Springs (a few hours’ drive north) that descended from a couple of rhesuses imported and released by a tour operator in the 1930s. In 2012, a rhesus macaque was captured more than 100 miles away, in Tampa. Admittedly, it might be unlikely to mistake a monkey for a skunk ape (macaques and baboons are generally only about two to three feet tall), but about 140 miles north of Shealy’s research headquarters, there’s the Center for Great Apes, a sanctuary that houses a few dozen retired or rescued chimps and orangutans.

This last species might be the most interesting, given best-known photographs of an alleged skunk ape, which arrived in an unmarked envelope at the Sarasota Sheriff’s Department along with an unsigned letter on December 22, 2000. The photos purportedly showed an animal that had repeatedly climbed onto the back deck of the photographers’ house, and the letter itself speculated that it was an escaped orangutan. Loren Coleman, an author and cryptozoology enthusiast, analyzed the creature’s anatomy and agreed with the orangutan hypothesis, as did Canadian Wildlife Service biologist Tony Scheuhammer.

Skunk ape enthusiasts, however, seized upon the images as further evidence of the legendary creature. Dave Shealy was no exception. “It doesn’t look exactly like what I’ve been seeing—the hair’s a little bit longer—but all the same, I think it was a skunk ape,” he told me when we discussed the photos.

All of this—the strange, hidden primate-breeding facility, the colonies of escaped monkeys, the great apes living farther north in Florida and the apparent evidence of an escaped orangutan—provided just enough opening to seriously consider the idea that the skunk ape was indeed a real ape, but a chimp or orangutan, rather than a new species. Maybe Shealy did film a person in a gorilla suit to produce the skunk ape photos and video, but only after seeing an actual ape cemented a genuine belief in the skunk ape in his mind. Perhaps he did so out of desperation—on the verge, he believed, of getting a state grant to further his research, but in need of hard evidence to land it—and driven further by the fear of losing his land, as profits from his tour operations dwindled.

If true, his moments of fraud would be irreparably unscientific. But his search, as a whole, is motivated by the same curiosity that drove Kristofer Helgen and Roland Kays to discover the olinguito. “Enthusiasts of cryptozoology are doing something noble,” said Peter Dendle, the folklore expert, even though he doesn’t believe in the existence of the skunk ape or any other cryptid. “They’re carrying on a tradition of exploration, and open-mindedness, and genuine inquiry, the spirit which has driven science for many centuries.”

* * *

Occasionally, in the swamp, if a pine tree dies under the right conditions, all of its resin is absorbed into its core, producing a waterproof, extremely flammable wood called lighter pine. But Native traditions, Shealy explained, held that the substance was the result of a bolt of lightning striking a tree, magically trapping all its energy inside. Similarly, during dry season, when the swamp’s water had dried up entirely, a sudden downpour would arrive, and within an hour, enormous catfish could be found swimming in the rising waters. They’d been living in underground gator holes, he said, but according to Native legend, they’d simply rained down from the heavens. “Both of those answers, technically, are incorrect,” Shealy told me. “But in their own way, they tell a story.”

He’d meant this as an allegory for the Native explanation of the skunk ape, but I realized it could be an analogy for Shealy’s beliefs as well. An unidentified primate escapes from a breeding facility and is spotted roaming across the swamp. It’s probably a chimpanzee or orangutan, but for any number of reasons—the need to retain control over a swamp that’s rapidly being taken over by outsiders, the desire to accomplish something truly noteworthy or the unconscious wish to maintain a vision of the world as a mysterious and unexplored place—Shealy says it’s a skunk ape.

His answer, technically, is incorrect. But in its own way, it tells a story.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7a/b5/7ab51f76-f2ec-4934-85c1-83af7ff90924/img_7127.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)