Tussling Over Thecodontosaurus

The history of Thecodontosaurus, the fourth dinosaur ever named, is a tangled tale of paleontologist politics

![]()

When British anatomist Richard Owen coined the term “Dinosauria” in 1842, there were nowhere near as many dinosaurs known as there are today. And even among that paltry lot, most specimens were isolated scraps that required a great deal of interpretation and debate to get right. The most famous of these enigmatic creatures were Megalosaurus, Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus–a trio of prehistoric monsters that cemented the Dinosauria as a distinct group. But they weren’t the only dinosaurs that paleontologists had found.

Almost 20 years before he established the Dinosauria, Owen named what he thought was an ancient crocodile on the basis of a tooth. He called the animal Suchosaurus, and only recently did paleontologists realize that the dental fossil actually belonged to a spinosaur, one of the heavy-clawed, long-snouted fish-eaters such as Baryonyx. Likewise, other naturalists and explorers discovered remnants of dinosaurs in North America and Europe prior to 1842, but no one knew what most of these fragments and fossil tidbits actually represented. Among these discoveries was the sauropodomorph Thecodontosaurus–a dinosaur forever connected with Bristol, England.

Paleontologist Mike Benton of the University of Bristol has traced the early history of Thecodontosaurus in a new paper published in the Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association. The story of the dinosaur’s discovery began in 1834, when reports of remains from “saurian animals” started to filter out of Bristol’s limestone quarries. Quarry workers took some of the bones to the local Bristol Institution for the Advancement of Science, Literature and Arts so that the local curator, Samuel Stutchbury, could see them. Yet Stutchbury was away at the time, so the bones were also shown to his paleontologist colleague Henry Riley, and when he returned Stutchbury was excited enough by the finds to ask quarrymen to bring him more specimens. He wasn’t the only one, though. David Williams–a country parson and geologist–had a similar idea, so Stutchbury teamed up with paleontologist Henry Riley in an academic race to describe the unknown creature.

All three naturalists issued reports and were aware of each other’s work. They collected isolated bones and skeletal fragments, studied them and communicated their preliminary thoughts to their colleagues at meeting and in print. In an 1835 paper, Williams even went so far as to suppose that the enigmatic, unnamed animal “may have formed a link between the crocodiles and the lizards proper”–not an evolutionary statement, but a proposal that the reptile slotted neatly into a static, neatly-graded hierarchy of Nature.

Riley, Stutchbury and Williams had become aware of the fossils around the same time in 1834. Yet Stuchbury and Williams, especially, were distrustful of each other. Stutchbury felt that Williams was poaching his fossils, and Williams thought Stutchbury was being selfish in trying to hoard all the fossils in the Bristol Institution. All the while, both parties worked on their own monographs about the animal.

Ultimately, Riley and Stuchbury came out on top. Williams lacked enough material to match the collection Riley and Stutchbury were working from, and he didn’t push to turn his 1835 report into a true description. He bowed out–and rightly felt snubbed by the other experts who had higher social standing–leaving the prehistoric animal to Riley and Stutchbury. No one knows why it took so long, but Riley and Stutchbury gave a talk about their findings in 1836, completed their paper in 1838 and finally published it in 1840. All the same, the abstract for their 1836 talk named the animal Thecodontosaurus and provided a short description–enough to establish the creature’s name in the annals of science.

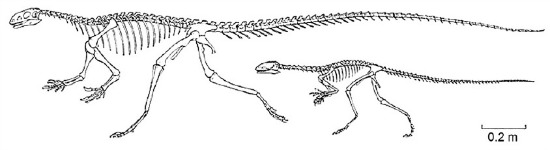

But Thecodontosaurus was not immediately recognized as a dinosaur. The concept of a “dinosaur” was still six years away, and, even then, Richard Owen did not include Thecodontosaurus among his newly-established Dinosauria. Instead, Thecodontosaurus was thought to be a bizarre, enigmatic reptile that combined traits seen in both lizards and crocodiles, just as Williams had said. It wasn’t until 1870 that Thomas Henry Huxley recognized that Thecodontosaurus was a dinosaur–now known to be one of the archaic, Triassic cousins of the later sauropod dinosaurs. Thecodontosaurus only held the faintest glimmerings of what was to come, though. This sauropodomorph had a relatively short neck and still ran about on two legs.

The tale of Thecodontosaurus was not only a story of science. It’s also a lesson about the way class and politics influenced discussion and debate about prehistoric life. Social standing and institutional resources gave some experts an edge over their equally enthusiastic peers. Paleontologists still grapple with these issues. Who can describe certain fossils, who has permission to work on a particular patch of rock and the contributions avocational paleontologists can make to the field are all areas of tension that were felt just as acutely in the early 19th century. Dinosaur politics remain entrenched.

For more information, visit Benton’s exhaustively-detailed “Naming the Bristol Dinosaur, Thecodontosaurus” website.

Reference:

Benton, M. (2012). Naming the Bristol dinosaur, Thecodontosaurus: politics and science in the 1830s Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 766-778 DOI: 10.1016/j.pgeola.2012.07.012

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)