Weather Prevents Different Giraffe Species From Interbreeding

In zoos, different giraffe species will readily mate, but if the species cross paths in Kenya, their rain-driven mating cycles won’t be in sync

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20131023044138giraffes-resized.jpg)

We tend to think of giraffes as a single species, but in Kenya not one but three types of giraffe occupy the same scruffy grasslands. These three species–the Masai, Reticulated and Rothschild’s giraffe–often encounter one another in the wild and look similar, but they each maintain a unique genetic makeup and do not interbreed. And yet, throw a male Masai and a female Rothschild’s giraffe, a male Rothschild or a female Reticulated–or any combination thereof–together in a zoo enclosure, and those different species will happily devote themselves to making hybrid giraffe babies.

What is it, then, that keeps these species apart in the wild?

Researchers from the University of California, Los Angeles, may be close to an answer. In nature, at least one of four potential barriers typically keeps similar-looking and similar-acting but distinct species from becoming intimate: distance, physical blocks, disparate habitats or seasonal differences, like rainfall. In the case of the Kenyan giraffes, the researchers could simply look at the habitat and know that physical barriers could probably be ruled out; no mountains, canyons or great bodies of water prevent the giraffes from finding one another. Likewise, giraffes sometimes have home ranges of up to 380 square miles, and those ranges may overlap. Distance alone, therefore, was probably not stopping the animals from meeting.

Either habitat or seasonal differences, they suspected, was the likely firewall preventing species from getting up close and personal with one another. To tease out the roles of these potential drivers, the authors built computer models that took into account a range of factors, including climate, habitat, human presence and genotypes from 429 giraffes that they sampled from 51 sites around Kenya. Just to make sure they weren’t unfairly excluding distance and physical obstacles from the list of possible dividers, they also included elevation values–some giraffes were found in the steep Rift Valley–and the distance between populations of giraffes sampled.

According to their statistical model, regional differences in rain–and the subsequent greening of the plains that it triggers–best explain genetic divergence between giraffe species, the researchers write in the journal PLoS One. East Africa experiences three different regional peaks in rain per year–April and May, July and August and December through March–and those distinct weather envelopes trisect Kenya.

So, although the trio of giraffe species sometimes overlap in range, the authors samples as well as previous studies revealed that they tend to each live and mate in one of those three geographic rain pockets, both within Kenya and throughout the greater East Africa region.

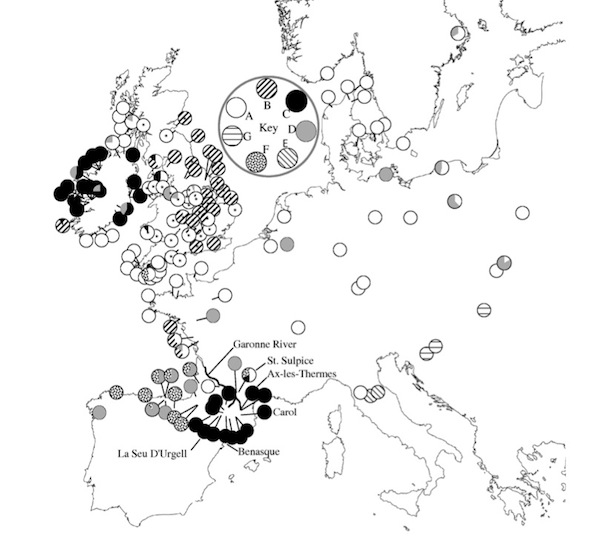

The researchers’ model used 10,000 randomly selected locations in Kenya to predict where each giraffe species would occur based on rainfall. Red corresponds with Rothschild’s, blue with Reticulated and green with Masai. The authors then overlaid those predictions with actual observations of where groups of those species occur. Crosses correspond with Masai, triangles with Rothschild’s and asterisks with Reticulated. Photo by Thomassen et. al, PLoS One

Giraffe species sync their pregnancies up with rain patterns to ensure enough vegetation is around to support the energetically taxing processes of gestation, birth and lactation for mother giraffes, the authors think. Not much information is available on giraffe births, but the few observations on this topic do confirm that giraffe species tend to have their babies during the local wet season, they report.

And while the models indicate that rain is the primary divider keeping giraffes apart, the authors point out that the animals also may be recognizing differences in one another’s coat patterns, for example. But scientists do not know enough about how giraffes chose mates or whether they can distinguish potential mates between species to give the species possible due credit for recognizing one another.

Whether rain alone or some combination of rain and recognition trigger mating, in the wild, at least, those mechanisms seem to work well for keeping giraffe species apart. It will be interesting to see whether this separation is maintained as climate changes.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)