The Western U.S. Could Soon Face the Worst Megadrought in a Millennium

Climate models predict that the region will be drier than the droughts that likely caused ancient Native Americans to abandon their pueblo cities

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9a/20/9a203db3-268c-4cbf-9d7f-e7bde5f6770d/42-33959512.jpg)

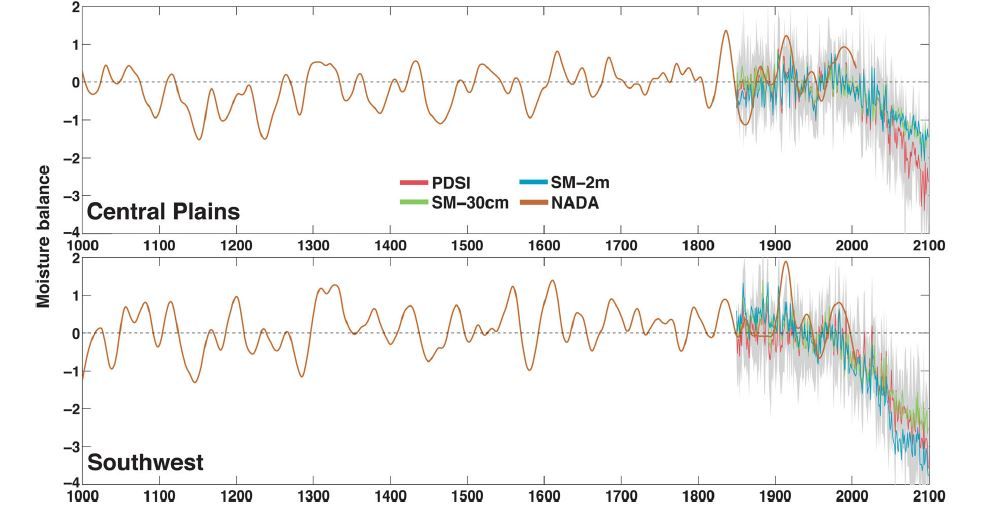

Without dramatic cuts to greenhouse gas emissions, the southwestern U.S. and Central Plains will suffer persistent drought in the latter half of the 21st century that would exceed even the worst droughts seen a millennium ago, says a new study. Those hot, dry conditions likely caused ancient Native Americans known as the Anasazi to abandon the pueblo cities at Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon.

The results, appearing today in the new journal Science Advances, suggest that the impacts of future megadroughts on modern society—including the agriculture and energy sectors—could be severe.

“The future looks fairly bleak, and it’s a future that all of us … need to pay attention to,” Marcia McNutt, editor-in-chief of the Science family of journals, said today at a press conference.

For the last decade, studies have been predicting that as temperatures rise due to anthropogenic climate change, the U.S. West faces an increasingly dry future. For instance, researchers reported last year in the Journal of Climate that the Southwest faced a 20 to 50 percent chance in the next century of a megadrought—a drought lasting 35 years or more.

The new study predicts an even bleaker future, showing “more convincingly than ever before that unchecked climate change will drive unprecedented drying across much of the United States—even eclipsing the huge megadroughts of medieval times,” says Jonathan Overpeck, co-director of the Institute of the Environment at the University of Arizona, who was not involved in the study.

To come up with their new predictions, Toby Ault of Cornell University and Benjamin Cook and Jason Smerdon of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory began with a record of climate from the past thousand years derived from tree rings. The width of a tree ring changes depending on how much moisture the tree receives in a given year. The team then used 17 different climate models to develop drought predictions for the next century for the Southwest and Central Plains under two scenarios: one in which greenhouse gas emissions continue unabated and a second in which they are moderated.

The models consistently predicted that the U.S. West is headed for drier times. The risk of a decades-long drought was high even under the moderate emissions scenario. With high emissions continuing, though, the risk was even greater—80 percent or more in the Southwest and at least 70 percent in the Central Plains.

“These future changes that we are seeing are likely to be more persistent than past megadroughts,” which occurred in a more stable past, Smerdon says.

The bad droughts of the past in this region have historically been driven by persistent La Niña conditions, when there are unusually cold waters in the Pacific. But the megadroughts of the not-too-distant future will be triggered by increased greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere, the report finds. The resulting changes to the climate will make these regions warmer, so that both the Southwest and the Central Plains will experience more evaporation, which will dry out the land. The Southwest will also experience reductions in winter precipitation.

“What’s important to realize is that continued warming is pretty much a sure bet without cuts in our greenhouse gas emissions, and this warming alone will likely overwhelm any increases in precipitation to dry out and bake a large swath of our country stretching from California through Texas," says Overpeck. "Decreases in precipitation will make the pain more acute where they occur.”

After the drought that sparked the Dust Bowl in the 1930s, the United States implemented conservation efforts and changed farming techniques in ways that have lessened the impacts of severe droughts. Irrigation, for instance, has let many farmers keep fields green even through dry times. And reservoirs have kept communities supplied with water.

Those methods, however, may not see Americans through the upcoming megadroughts, the researchers warn. Giant reservoirs such as Lake Mead have been shrinking due to drought and overuse, threatening water and energy supplies. Groundwater supplies are also being depleted faster than rains can recharge them.

Now entering its fourth consecutive year of drought, California is already starting to encounter some of those limits. In that state, no reservoir is above half full, and farmers may not be able to obtain as much water as they need come spring. Groundwater supplies are being depleted. Wells have run dry.

“Humans act as a positive feedback on hydrological drought,” says James Famiglietti, of the University of California, Irvine. “The drier it gets, the more groundwater we use, and as a result, we accelerate drying. The results presented in this paper could not be any more dismal.”

But there is still time to head off that future, he says. “The good news is that we have ample warning and know what to do to stop the unprecedented drying from becoming reality—we just need to make serious cuts in greenhouse gas emissions,” Famiglietti notes. “Otherwise the next generations of Americans are going to have a huge problem on their hands.”

The one bright note, Ault says, is that past megadroughts were recorded in tree rings, which meant that the trees survived even those ultra-dry conditions. “I am optimistic that we can cope with the threat of megadrought in the future because it doesn’t mean no water,” he says. “It means significantly less water than we are used to.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)