What Are the Acoustic Wonders of the World?

Sonic engineer Trevor Cox is on a mission to find the planet’s most interesting sounds

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/83/65/83651fa5-74bd-4789-b459-7aa459dbea18/jokulsarlon_lagoon_in_southeastern_iceland.jpg)

Acoustic engineer Trevor Cox was inspired to embark on his life's grandest quest when he climbed down to the bottom of a sewer.

An expert who designs treatments to optimize the acoustics of concert halls and lecture rooms, Cox was participating in a TV interview on the acoustics of sewers when he was struck by something. "I heard something interesting down there, a sound sprialing around the sewer," he says. "It kind of took me by surprise, and it got me thinking: what other remarkable sounds are out there?"

Eventually, this line of thought led him to take up a new mission: finding the sonic wonders of the world. He set up a website and began his research, traveling to ancient mausoleums with strange acoustics, icebergs that creak and groan naturally and a custom-built organ called the Stalacpipe that harnesses the reverberations of stalactites in a Virginia cave. His new book, The Sound Book, catalogs his journeys to these locales. "They're places that you want to visit not for the more typical reason, that they've got beautiful views, but because they've got beautiful sounds," he says.

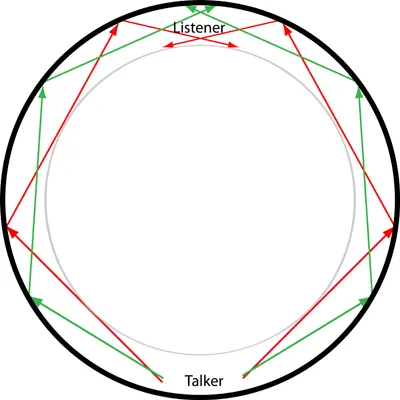

Some of the acoustic destinations were relatively obvious. On example is the well-known St. Paul's Cathedral's whispering gallery, so called because a speaker standing against the gallery wall can whisper and be heard by someone standing against the wall on the opposite side of the room. This occurs because the walls of the room are perfectly cylindrical, so sound waves directed at the proper angle can bounce form one side to another without losing much volume.

But there are many other whispering galleries that produce even more remarkable acoustic effects than St. Paul's and are much less well-known. Once such room is a Cold War-era spy listening station in Berlin, used by British and American spies to listen in on East German radio communications. Because the room is pretty much spherical, the whispering gallery effect is even more magnified.

Making noise at the center of the room, meanwhile, leads to a bizarre sound distortion, as the sound waves bounce off the walls and return together cacaphonously. "You get all sorts of strange effects," Cox says. "I knelt down to unzip my rucksack, and it sounded like I was unzipping the bag from above my head."

One of the most remarkable sites Cox visited is an abandoned oil tank in Inchindown, in the Scottish highlands, buried deep in a hillside in the 1940's to protect it from German bombing campaigns. "It's this vast space, the size of a small cathedral, and there's absolutely no light besides your flashlight," he says. "You don't realize how big it really it until you make a sound, and then the echo just goes on and on."

The extreme length of the echo, in fact, made Cox suspect the tank could overtake Hamilton Mausoleum, also in Scotland, which previously held the record for the world's longest echo. As a test, he shot a blank cartridge in the tank from a pistol, and timed the resulting reverberation at 75 seconds, giving the buried chamber the record.

Many of Cox's sonic wonders are the result of natural phenomena. He visited several areas in which sand dunes can naturally hum or drone, including the Kelso Dunes in the Mojave Desert, one of about 40 droning dune sites worldwide.

In certain conditions, small avalanches of sand falling down these dunes can produce strange, deep humming sounds. The science of this effect still isn't entirely understood, but the production of the sounds is dependent on grain size and shape, as well as the moisture level of the falling sand.

Cox traveled to the Mojave during the summer—when the already-arid area is at its driest, increasing the likelihood of droning—specifically to hear the sound. His first night, he heard nothing, but the next morning he and friends were able to generate the sound by pushing sand down the dunes.

Cox traveled elsewhere to hear some of the strangest sounds naturally made by animals. Among the most unusual, he found, are the calls of Alaska's bearded seals, which sound distinctly like alien noises from a 1950's sci-fi movie.

"The bearded seal produces incredibly complex vocalisations, with the long drawn out glissandos that trill and spiral down in frequency," Cox writes. Because the calls are intended to attract the attention of females, scientists believe that evolutionary pressures push male seals to make more and more outlandish sounds, resulting in the extraordinarily weird calls like the one below, recorded using an underwater microphone in Point Barrow, Alaska.

One of Cox's biggest takeaways from the project, though, is that acoustic tourism can be done virtually anywhere. Even in his hometown of Salford, near the city of Manchester, there are interesting sounds worth listening.

"As I wrote the book, I became more and more aware of interesting sounds during the everyday," he says, "and I now find myself listening more and more as I walk around. At the moment, spring is on its way, so I hear the animals coming alive. Even above the rumble of the traffic, I notice bird song coming back after a long winter."

All sound recordings courtesy of Trevor Cox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)