What Does It Mean to Be a Species? Genetics Is Changing the Answer

As DNA techniques let us see animals in finer and finer gradients, the old definition is falling apart

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ce/91/ce9123c1-79e5-430a-a6c6-3d01c65aca7c/darwins_finches_by_gould.jpg)

For Charles Darwin, "species" was an undefinable term, "one arbitrarily given for the sake of convenience to a set of individuals closely resembling each other." That hasn't stopped scientists in the 150 years since then from trying, however. When scientists today sit down to study a new form of life, they apply any number of more than 70 definitions of what constitutes a species—and each helps get at a different aspect of what makes organisms distinct.

In a way, this plethora of definitions helps prove Darwin’s point: The idea of a species is ultimately a human construct. With advancing DNA technology, scientists are now able to draw finer and finer lines between what they consider species by looking at the genetic code that defines them. How scientists choose to draw that line depends on whether their subject is an animal or plant; the tools available; and the scientist’s own preference and expertise.

Now, as new species are discovered and old ones thrown out, researchers want to know: How do we define a species today? Let’s look back at the evolution of the concept and how far it’s come.

Perhaps the most classic definition is a group of organisms that can breed with each other to produce fertile offspring, an idea originally set forth in 1942 by evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr. While elegant in its simplicity, this concept has since come under fire by biologists, who argue that it didn't apply to many organisms, such as single-celled ones that reproduce asexually, or those that have been shown to breed with other distinct organisms to create hybrids.

Alternatives arose quickly. Some biologists championed an ecological definition that assigned species according to the environmental niches they fill (this animal recycles soil nutrients, this predator keeps insects in check). Others asserted that a species was a set of organisms with physical characteristics that were distinct from others (the peacock's fanned tail, the beaks of Darwin's finches).

The discovery of DNA's double helix prompted the creation of yet another definition, one in which scientists could look for minute genetic differences and draw even finer lines denoting species. Based on a 1980 book by biologists Niles Eldredge and Joel Cracraft, under the definition of a phylogenetic species, animal species now can differ by just 2 percent of their DNA to be considered separate.

"Back in 1996, the world recognized half the number of species of lemur there are today," says Craig Hilton-Taylor, who manages the International Union for the Conservation of Nature's Red List of threatened species. (Today there are more than 100 recognized lemur species.) Advances in genetic technology have given the organization a much more detailed picture of the world's species and their health.

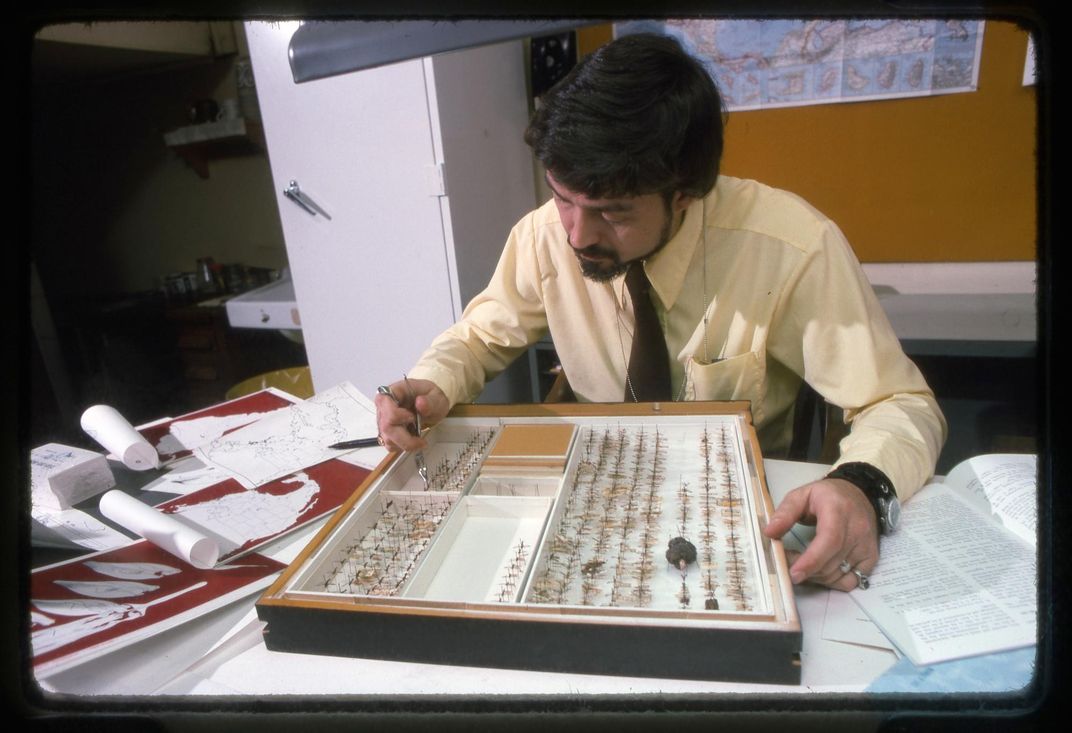

These advances have also renewed debates about what it means to be a species, as ecologists and conservationists discover that many species that once appeared singular are actually multitudes. Smithsonian entomologist John Burns has used DNA technology to distinguish a number of so-called "cryptic species"—organisms that appear physically identical to a members of a certain species, but have significantly different genomes. In a 2004 study, he was able to determine that a species of tropical butterfly identified in 1775 actually encompassed 10 separate species.

In 2010, advanced DNA technology allowed scientists to solve an age-old debate over African elephants. By sequencing the rarer and more complex DNA from the nuclei of elephant cells, instead of the more commonly used mitochondrial DNA, they determined that African elephants actually comprised two separate species that diverged millions of years ago.

"You can no more call African elephants the same species as you can Asian elephants and the mammoth," David Reich, a population geneticist and lead author on the study, told Nature News.

In the wake of these and other paradigm-shifting discoveries, Mayr’s original concept is rapidly falling apart. Those two species of African elephants, for instance, kept interbreeding as recently as 500,000 years ago. Another example falls closer to home: Recent analyses of DNA remnants in the genes of modern humans have found that humans and Neanderthals—usually thought of as separate species that diverged roughly 700,000 years ago—interbred as recently as 100,000 years ago.

So are these elephants and hominids still separate species?

This isn't just an argument of scientific semantics. Pinpointing an organism's species is critical for any efforts to protect that animal, especially when it comes to government action. A species that gets listed on the U.S. Endangered Species Act, for example, gains protection from any destructive actions from the government and private citizens.These protections would be impossible to enforce without the ability to determine which organisms are part of that endangered species.

At the same time, advances in sequencing techniques and technology are helping today’s scientists better piece together exactly which species are being impacted by which human actions.

"We're capable of recognizing almost any species [now]," says Mary Curtis, a wildlife forensic scientist who leads the genetics team at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Forensics Laboratory. Her lab is responsible for identifying any animal remains or products that are suspected to have been illegally traded or harvested. Since adopting DNA sequencing techniques more than 20 years ago, the lab has been able to make identifications much more rapidly, and increase the number of species it can reliably recognize by the hundreds.

"A lot of the stuff we get in in genetics has no shape or form," Curtis says. The lab receives slabs of unidentified meat, crafted decorative items or even the stomach contents of other animals. Identifying these unusual items is usually out of the reach of taxonomic experts using body shape, hair identification and other physical characteristics. "We can only do that with DNA," Curtis says.

Still, Curtis, who previously studied fishes, doesn't discount the importance of traditional taxonomists. "A lot of the time we're working together," she says. Experienced taxonomists can often quickly identify recognizable cases, leaving the more expensive DNA sequencing for the situations that really need it.

Not all ecologists are sold on these advances. Some express concerns about "taxonomic inflation," as the number of species identified or reclassified continues to skyrocket. They worry that as scientists draw lines based on the narrow shades of difference that DNA technology enables them to see, the entire concept of a species is being diluted.

"Not everything you can distinguish should be its own species," as German zoologist Andreas Wilting told the Washington Post in 2015. Wilting had proposed condensing tigers into just two subspecies, from the current nine.

Other scientists are concerned about the effects that reclassifying once-distinct species can have on conservation efforts. In 1973, the endangered dusky seaside sparrow, a small bird once found in Florida, missed out on potentially helpful conservation assistance by being reclassified as a subspecies of the much more populous seaside sparrow . Less than two decades later, the dusky seaside sparrow was extinct.

Hilton-Taylor isn’t sure yet when or how the ecological and conservation communities will settle on the idea of a species. But he does expect that DNA technology will have a significant impact on disrupting and reshaping the work of those fields. “Lots of things are changing,” Hilton-Taylor says. “That's the world we're living in.”

This uncertainty is in many ways reflective of the definition of species today too, Hilton-Taylor says. The IUCN draws on the expertise of various different groups and scientists to compile data for its Red List, and some of those groups have embraced broader or narrower concepts of what makes a species, with differing reliance on DNA. “There's such a diversity of scientists out there,” Hilton-Taylor says. “We just have to go with what we have.”