What Makes the “Lion Whisperer” Roar?

He’s famous for getting dangerously close to his fearsome charges, but what can Kevin Richardson teach us about ethical conservation—and ourselves?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/89/bc/89bc1741-8f44-4a7a-8ce8-2a307be134fb/jun2015_e09_lions_1.jpg)

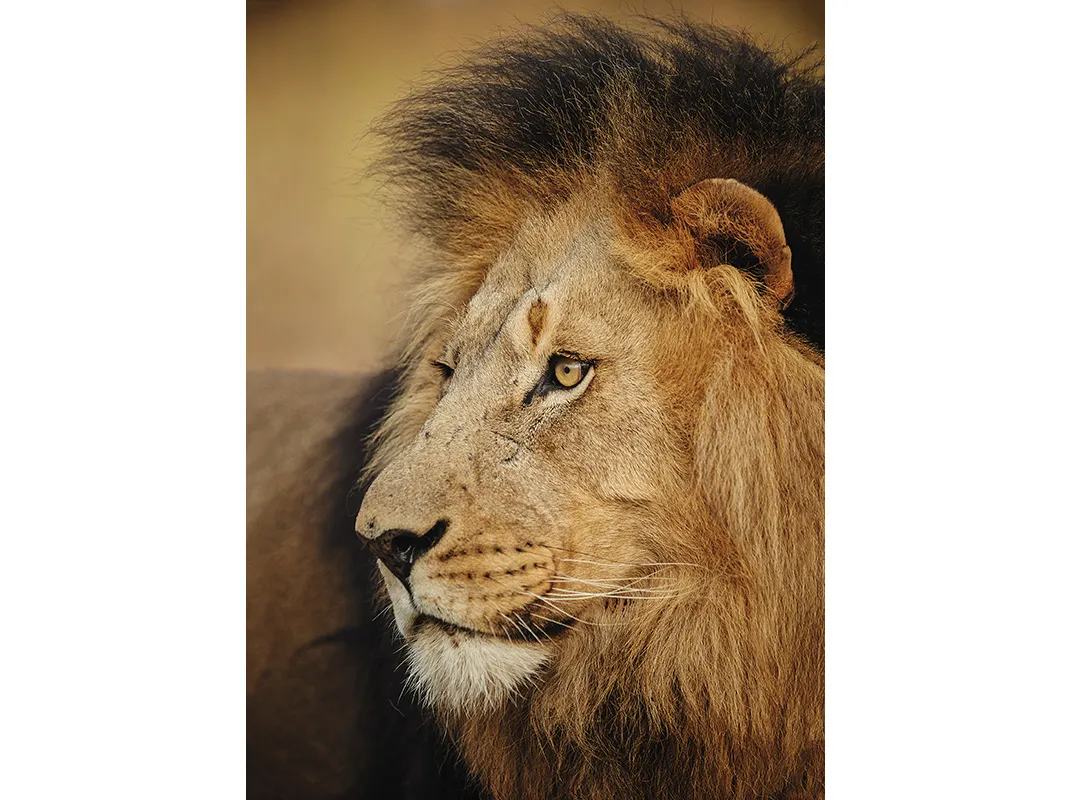

One recent morning, Kevin Richardson hugged a lion and then turned away to check something on his phone. The lion, a 400-pound male with paws the size of dinner plates, leaned against Richardson’s shoulder and gazed magnificently into middle space. A lioness lolled a few feet away. She yawned and stretched her long tawny body, swatting lazily at Richardson’s thigh. Without taking his eyes from his phone screen, Richardson shrugged her off. The male lion, now having completed his moment of contemplation, began gnawing on Richardson’s head.

If you were present during this scene, unfolding on a grassy plain in a northeast corner of South Africa, this would be exactly when you would appreciate the sturdiness of the security fence that stood between you and the pair of lions. Even so, you might take a quick step back when one of the animals turned its attention away from Richardson and for an instant locked eyes with you. Then, noting which side of the fence Richardson was on, you might understand why so many people place bets on when he will be eaten alive.

**********

Richardson was referred to as the “lion whisperer” by a British newspaper in 2007, and the name stuck. There is probably no one in the world with a more recognized relationship with wild cats. The most popular YouTube video of Richardson frolicking with his lions has been viewed more than 25 million times and has more than 11,000 comments. The scope of reactions is epic, ranging from awe to respect to envy to bafflement: “If he does die he will die in his own heaven doing what he loves” and “This guy chilling with lions like they’re rabbits” and many versions of “I want to get to do what he does.”

The first time I saw one of Richardson’s videos, I was transfixed. After all, every fiber in our being tells us not to cozy up with animals as dangerous as lions. When someone defies that instinct, it seizes our attention like a tightrope walker without a net. I was puzzled by how Richardson managed it, but just as much by why. Was he a daredevil with a higher threshold for fear and danger than most people? That might explain it if he were dashing in and out of a lion’s den on a dare, performing a version of seeing how long you can hold your hand in a flame. But it’s clear that Richardson’s lions don’t plan to eat him, and that his encounters aren’t desperate scrambles to stay a step ahead of their claws. They snuggle up to him, as lazy as house cats. They nap in a pile with him. They aren’t tame—he is the only person they tolerate peaceably. They simply seem to have accepted him in some way, as if he were an odd, furless, human-shaped lion.

Watch "Killer IQ: Lion Vs. Hyena"

Check local listings on Smithsonian Channel

How we interact with animals has preoccupied philosophers, poets and naturalists for ages. With their parallel and unknowable lives, animals offer us relationships that exist in the realm of silence and mystery, distinct from those we have with others of our own species. A rapport with domesticated animals is familiar to all of us, but anyone who can have that kind of relationship with wild animals seems exceptional, perhaps a little mad. Some years ago, I read a book by the writer J. Allen Boone in which he detailed his connection with all manner of creatures, including a skunk and the actor dog Strongheart. Boone was especially proud of the friendship he developed with a housefly he named Freddie. Whenever Boone wanted to spend time with Freddie, he “had only to send out a mental call” and Freddie would appear. The man and his fly did household chores and listened to the radio together. Like Richardson’s lions, Freddie wasn’t tame—he had an exclusive relationship with Boone. In fact, when an acquaintance of Boone’s insisted on seeing Freddie so he could experience this connection, the fly seemed to sulk and refused to be touched.

Befriending a housefly, crazy as it seems, raises the question of what it means when we bond across species. Is there anything to it beyond the amazing fact that it has been accomplished? Is it a mere oddity, a performance that is revealed to signify nothing special or important after the novelty has worn off? Does it violate something fundamental—a sense that wild things should eat us or sting us or at least avoid us, not snuggle us—or is it valuable because it reminds us of a continuity with living creatures that is easily forgotten?

**********

Because of his great naturalness with wildlife, you might expect that Richardson grew up in the bush, but he is the product of a Johannesburg suburb with sidewalks and streetlamps and not even a whiff of jungle. The first time he laid eyes on a lion was on a first-grade field trip to the Johannesburg Zoo. (He was impressed, but he also remembers thinking it odd that the king of the jungle existed in such reduced circumstances.) He found his way to animals anyway. He was the kind of kid who kept frogs in his pockets and baby birds in shoeboxes, and he mooned over books like Memories of a Game Ranger, Harry Wolhuter’s account of 44 years as a ranger in Kruger National Park.

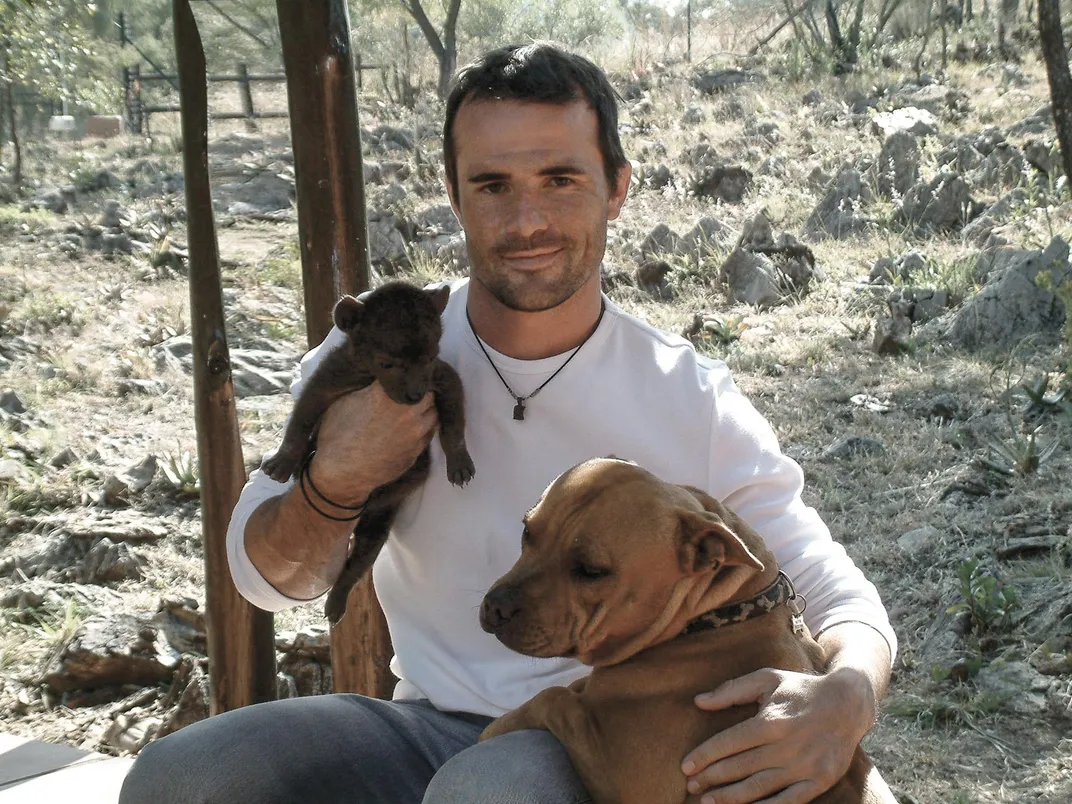

Richardson was a rebellious youngster, a hell-raiser. He is now 40 years old, married and the father of two young children, but it is still easy to picture him as a joy-riding teenager, rolling cars and slamming back beers. During that period, animals were pushed to the margins of his life, and he came back to them in an unexpected way. In high school, he dated a girl whose parents included him on family trips to national parks and game reserves, which reignited his passion for wildlife. The girl’s father was a South African karate champion, and he encouraged Richardson to take up physical fitness. Richardson embraced it so enthusiastically that, when he didn’t get accepted to veterinary school, he decided to get a degree in physiology and anatomy instead. After college, while working in a gym as a trainer, he became friendly with a client named Rodney Fuhr, who had made a fortune in retail. Like Richardson, he was keen on animals. In 1998, Fuhr bought a faded tourist attraction called Lion Park, and he urged Richardson to come see it. Richardson says he knew little about lions at the time, and his first trip to the park was a revelation. “I met two 7-month-old cubs, Tau and Napoleon,” he says. “I was mesmerized and terrified, but most of all, I had a really profound experience. I visited those cubs every day for the next eight months.”

**********

When you visit Richardson in the Dinokeng Game Reserve, now home to a wildlife sanctuary that bears his name, you have little hope for uninterrupted sleep. The lions wake up early, and their roars rumble and thunder through the air when the sky is still black with night.

Richardson wakes up early, too. He is dark-haired and bright-eyed, and has the handsome, rumpled look of an actor in an after-shave commercial. His energy is impressive. When he isn’t running around with lions, he likes to ride motorcycles and fly small planes. He is the first to admit to a hardy appetite for adrenaline and a tendency to do things to an extreme. He is also capable of great tenderness, cooing and sweet-talking his lions. On my first morning at the reserve, Richardson hurried me over to meet two of his favorite lions, Meg and Ami, whom he has known since they were cubs at Lion Park. “Such a pretty, pretty, pretty girl,” he murmured to Ami, and for a moment, it was like listening to a little boy whispering to a kitten.

When Lion Park first opened, in 1966, it was revolutionary. Unlike zoos of that era, with their small, bare enclosures, Lion Park allowed visitors to drive through a property where wildlife wandered loose. The array of African plains animals, including giraffes, rhinoceroses, elephants, hippopotamuses, wildebeests and a variety of cats, had once thrived in the area, but the park is on the outskirts of Johannesburg, an enormous urban area, and over the previous century most of the land in the region has been developed for housing and industry. The rest has been divvied up into cattle ranches, and fences and farmers have driven the large game animals away. Lions, in particular, were long gone.

Once enjoying the widest global range of almost any land mammal, lions now live only in sub-Saharan Africa (there is also a remnant population in India). In the last 50 years, the number of wild lions in Africa has dropped by at least two-thirds, from 100,000 or more in the 1960s (some estimates are as high as 400,000) to perhaps 32,000 today. Apart from Amur tigers, lions are the largest cats on earth, and they hunt large prey, so the lion ecosystem needs open territory that is increasingly scarce. As apex predators, lions have no predators of their own. What accounts for their disappearance, in part, is that they have been killed by farmers when they’ve ventured onto ranch land, but most of all, they have been squeezed out of existence as the open spaces have vanished. In most of Africa, there are far more lions in captivity than in the wild. Lion Park had to be stocked with animals; its pride of Panthera leo were retired circus lions who had probably never seen a natural environment in their lives.

The most popular feature at Lion Park wasn’t the safari drive; it was Cub World, where visitors could hold and pet lion cubs. And no one could resist it. Unlike lots of other animals that could easily kill us—alligators, say, or poisonous snakes—lions are gorgeous, with soft faces and snub noses and round, babyish ears. As cubs, they are docile enough for anyone to cuddle. Once the cubs are too big and strong to be held, at around 6 months, they often graduate to a “lion walk,” where, for an additional fee, visitors can stroll beside them in the open. By the time the lions are 2 years old, though, they are too dangerous for any such interactions. A few might be introduced to a park’s “wild” pride, but simple math tells the real story: Very quickly, there are more adult lions than there is room in the park.

Richardson became obsessed with the young lions and spent as much time as he could at Cub World. He discovered he had a knack for relating to them that was different and deeper than what the rest of the visitors and staff had; the animals seemed to respond to his confidence and his willingness to roar and howl his version of lion language. Lions are the most social of big cats, living in groups and collaborating on hunting, and they are extremely responsive to touch and attention. Richardson played with the cubs as if he were another lion, tumbling and wrestling and nuzzling. He got bitten and clawed and knocked over frequently, but he felt the animals accepted him. The relationship sustained him. “I can relate to feeling so alone that you are happiest with animals,” he says. He became most attached to Tau and Napoleon, and to Meg and Ami. He began spending so much time at the park that Fuhr gave him a job.

At first, Richardson didn’t think about what became of the lions that had aged out of petting and walking. He says he remembers vague mention of a farm somewhere where the surplus lions lived, but he admits that he let naiveté and willful denial keep him from considering it further. One thing is certain: None of the Cub World animals—or any cubs from similar petting farms popping up around South Africa—were successfully introduced to the wild. Having been handled since birth, they were not fit for living independently. Even if they were, there was nowhere for them to be released. South Africa’s wild lions are sequestered in national parks, where they are monitored and managed to assure they have sufficient range and prey. Each park has as many lions as it can accommodate. There is no spare room at all, and this presents a counterintuitive proposition: that successful lion conservation depends not on increasing the lion population but in recognizing that it is already probably too large for the dwindling habitats that can sustain it. Lions are not in short supply; space for them to live wild, however, is.

Some of the surplus animals from petting facilities end up in zoos and circuses; others are sent to Asia, where their bones are used in folk medicine. Many are sold to one of the roughly 180 registered lion breeders in South Africa, where they are used to produce more cubs. Cub petting is a profitable business, but there is a constant need for new cubs, since each one can be used only for a few months. According to critics, breeders remove newborns from their mothers shortly after birth, so the females can be bred again immediately, rather than waiting for them to go through nursing and weaning. Of the approximately 6,000 captive lions in South Africa, most live in breeding farms, cycling through pregnancy over and over again.

The rest of the extra lions end up as trophies in commercial hunts, in which they are held in a fenced area so they have no chance to escape; sometimes they are sedated so that they are easier targets. These “canned” hunts charge up to $40,000 to “hunt” a male lion, and around $8,000 for a female. The practice is big business in South Africa, where it brings in nearly a hundred million dollars a year. Up to 1,000 lions are killed in canned hunts in South Africa annually. The hunters come from all over the world, but most are from the United States. In an email, Fuhr acknowledged that cubs raised at Lion Park had in the past ended up as trophies in canned hunts. He expressed regret and said that he has instituted strict new policies to “ensure the best that is possible that no lions end up at hunting operations.”

**********

One day, Richardson arrived at Lion Park and discovered that Meg and Ami were gone. The park’s manager told him that they had been sold to a breeding farm. After Richardson made a fuss, Fuhr finally agreed to arrange for their return. Richardson raced to retrieve them from the farm that he says was an astonishing sight—a vast sea of lionesses in crowded corrals. This was Richardson’s moment of reckoning: He realized he had no control over the fate of the animals he was so attached to. Cub petting provided financial incentive to breed captive lions, resulting in semi-tame cubs who had no reasonable future anywhere. He was part of a cycle that was dooming endless numbers of animals. But, he says, “Selfishly, I wanted to keep my relationship with my lions.”

Thanks to a television special featuring him in one of his lion embraces, Richardson had begun to attract international attention. He was now in an untenable position, celebrating the magnificence of lions but doing so by demonstrating an unusual ease with them, something that seemed to glorify the possibility of taming them. And he was doing so while working at a facility that contributed to their commodification. At the same time, he felt directly responsible for 32 lions, 15 hyenas and four black leopards, and had no place for them to go. “I started thinking, How do I protect these animals?” he says.

In 2005, Fuhr began working on a film called White Lion, about an outcast lion facing hardship on the African plains, and Richardson, who was co-producing it and managing the animal actors, traded his fee for half-ownership in his menagerie. With Fuhr’s approval, he moved them from Lion Park to a farm nearby. In time, though, his relationship with Fuhr came undone, and Richardson finally left his job at Lion Park. He viewed it as a chance to reinvent himself. While he had become famous because of his ability to, in effect, tame lions, he wanted to work for the goal of keeping wild ones wild. It’s a balancing act, one that could be criticized as a case of do-as-I-say-not-as-I-do, and Richardson is aware of the contradictions. His explanation is that his lions are exceptional, formed by the exceptional circumstances in which they were raised. They shouldn’t be a model for future lion-human interactions.

“If I didn’t utilize my relationship with the lions to better the situation of all lions, it would just be self-indulgent,” Richardson says. “But my ‘celebrity,’ my ability to interact with the lions, has meant I’ve had more impact on lion conservation.” He believes that helping people appreciate the animals—even if it’s in the form of fantasizing about hugging one—will ultimately motivate them to oppose hunting and support protection.

A few years ago, Richardson met Gerald Howell, who, along with his family, owned a farm abutting Dinokeng Game Reserve, the largest wildlife preserve in the Johannesburg area. The Howells and many nearby farmers had taken down the fences between their properties and the park, effectively adding huge amounts of land to the 46,000-acre reserve. Now the Howells run a safari camp for visitors to Dinokeng. Howell offered Richardson a section of his farm for his animals. After building shelters and enclosures on the Howell farm for his lions, hyenas and leopards, Richardson moved them to what he hopes will be their permanent home.

**********

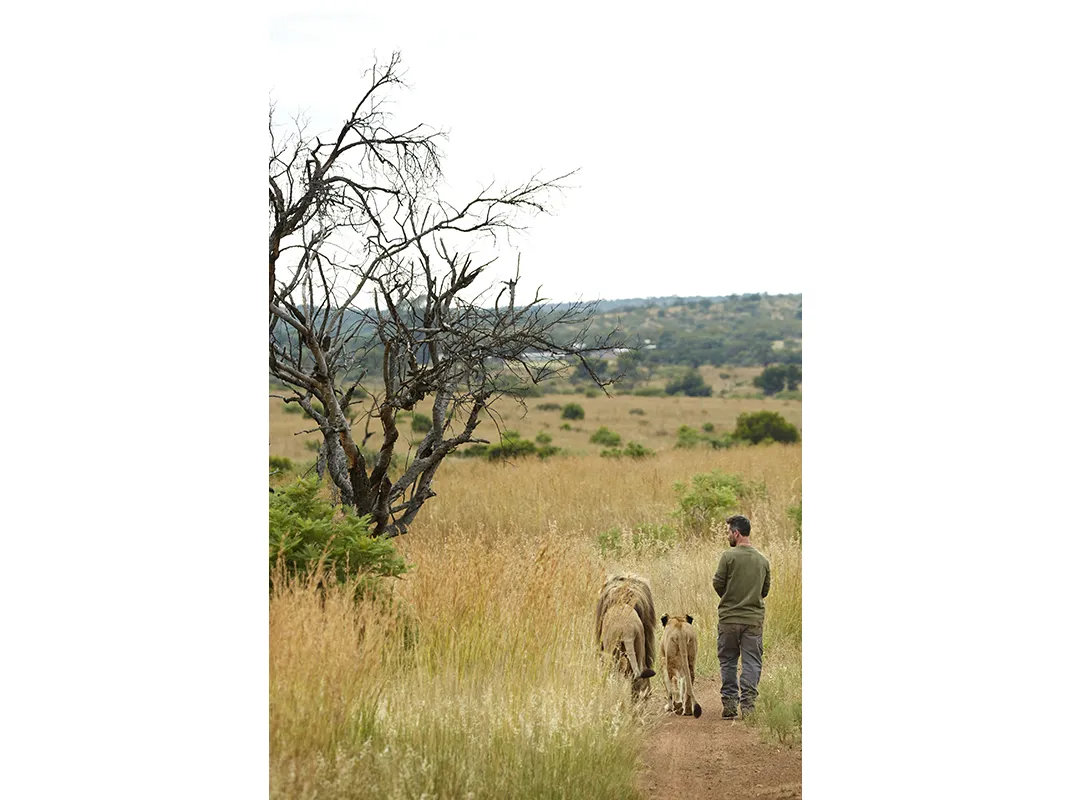

There was rain in the forecast the week I visited, and every morning the clouds draped down, swollen and gray, but it was still nice enough weather for taking a lion out on a walk. Richardson’s animals live in simple, spacious enclosures. They aren’t free to roam at will, because they can’t mix with Dinokeng’s population of wild lions, but Richardson tries to make up for that by taking them out in the park frequently, letting them roam under his supervision. “In a way, I’m a glorified jailer,” he says. “But I try to give them the best quality of life they can possibly have.” After a lion-roar wake-up call, Richardson and I left the safari camp and drove across Dinokeng’s rumpled plains of yellow grass and acacia trees and black, bubbling termite hills. Bush willows uprooted by foraging elephants were piled like pickup sticks beside the road. In the distance, a giraffe floated by, its head level with the treetops.

That day, it was Gabby and Bobcat’s turn for a walk, and as soon as they saw Richardson’s truck pulling up they crowded up to the fence, pacing and panting. They seemed to radiate heat; the air pulsed with the tangy scent of their sweat. “Hello, my boy,” Richardson said, ruffling Bobcat’s mane. Bobcat ignored him, blinking deeply, shifting just enough to allow Richardson room to sit down. Gabby, who is excitable and rascally, flung herself on Richardson, wrapping her massive front legs around his shoulders. “Oof,” Richardson said, getting his balance. “OK, yes, hello, hello my girl.” He tussled with her for a moment and pushed her down. Then he checked an app on his phone to see where Dinokeng’s eight wild lions had congregated that morning. Each of the wild lions wears a radio collar that transmits its location; the lions show up as little red dots on the map. Lions, in spite of their social nature, are ruthlessly territorial, and fighting among rival prides is one of the leading causes of death. “We definitely don’t want to run into the wild lions when we take these guys out for a walk,” Richardson said. “Otherwise, that would be curtains. A bloodbath.”

After setting our course, Richardson loaded Gabby and Bobcat into a trailer and we headed into the park, the truck juttering and clattering in the ruts in the road. Guinea fowl, their blue heads bobbing, strutted in manic circles in front of us, and a family of warthogs scampered by, bucking and squealing. At a clearing, we rolled to a stop, and Richardson climbed out and opened the trailer. The lions jumped down, landing without a sound, and then bounded away. A herd of waterbuck grazing in the scrub nearby spun to attention, flashing their white rumps. They froze, staring hard, moon-faced and vigilant. Occasionally, Richardson’s lions have caught prey on their walks, but most of the time they stalk and then lose interest, and come running back to him. More often, they stalk the tires on the truck, which apparently is good fun if you’re looking to bite something squishy.

I asked why the lions don’t just take off once they are loose in the park. “Probably because they know where they get food, and just out of habit,” Richardson said. Then he grinned and added, “I’d like to think it’s also because they love me.” We watched Gabby inch toward the waterbuck and then explode into a run. The herd scattered, and she wheeled around and headed back toward Richardson. She heaved herself at him, 330 muscular pounds going full-speed, and even though I had seen him do this many times, and watched all the videos of him in many such energetic encounters, and had heard him explain how he trusts the lions and they trust him, my heart lurched, and for a split second the sheer illogic of a man and a lion in a warm embrace rattled around in my head. Richardson cradled Gabby for a moment, saying, “That’s my girl, that’s my girl.” Then he dropped her down and tried to direct her attention to Bobcat, who was rubbing his back against an acacia tree nearby. “Gabby, go ahead,” he said, nudging her. “Go, go, my girl, go!”

She headed back to Bobcat, and the two of them trotted down the path, away from us, small birds bursting out of the brush as they passed by. They moved quickly, confidently, and for a moment it looked as if they were on their own, lording over the landscape. It was a beautiful illusion, because even if they forsook their relationship with Richardson and ran off they would soon come to the fenced perimeter of the park, and their journey would end. And those constraints are not just present here in Dinokeng: all of South Africa’s wilderness areas, like many throughout Africa, are fenced in, and all of the animals in them are, to some extent, managed—their roaming contained, their numbers monitored. The hand of humanity lies heavily on even the farthest reaches of the most remote-seeming bush. We have ended up mediating almost every aspect of the natural world, muddling the notion of what being truly wild can really mean anymore.

Rain began to dribble down from the darkening sky and a light wind picked up, scattering bits of brush and leaves. Richardson checked his watch, and then hooted to the lions. They circled back, took a swipe at the truck tires, and then hopped into the trailer for the ride home. Once they were locked in, Richardson handed me a treat to feed to Gabby. I held my hand flat against the bars of the trailer and she scooped the meat away with her tongue. After she swallowed, she fixed one golden eye on me, took my measure, and then slowly turned away.

**********

Richardson would like to make himself obsolete. He imagines a world in which we do not meddle with wild animals at all, no longer creating misfits that are neither wild nor tame, out of place in any context. In such a world, lions would have enough space to be free, and places like his sanctuary wouldn’t be necessary. He says that if cub petting and canned hunting were stopped immediately, he would give up all of his lions. He means this as a way to illustrate his commitment to abolishing the practices rather than it being an actual possibility, since cub petting and canned hunting aren’t likely to be stopped any time soon, and in reality his lions will be dependent on him for the rest of their lives. They have all known him since they were a few months old. But now most of them are middle-aged or elderly, ranging from 5 to 17 years old. A few, including Napoleon, the first lion who enchanted him at Cub World, have died. Since he has no plans to acquire young lions, though, at some point they will all be gone.

Sometimes, in spite of your firmest intentions, plans change. A few months ago, Richardson was contacted by a lion rescue organization, which had seized two malnourished lion cubs from a theme park in Spain and hoped he would provide a home for them. He first said no, but then relented, in part because he knew the cubs would never be entirely healthy and would have a hard time finding another place to go. He is proud of how they’ve thrived since they came to Dinokeng, and when we stopped by their nursery later that day, it was clear how much he loved being near them. Watching him with lions is a strange and marvelous sort of magic trick—you don’t quite believe your eyes, and you’re not even sure what it is that you’re seeing, but you thrill to the mere sight of it and the possibility that it implies. The cubs, George and Yame, tumbled on the ground, clawing at Richardson’s shoes and chewing on his laces. “After them, that’s it,” he said, shaking his head. “Twenty years from now, the other lions will be gone, and George and Yame will be old. I’ll be 60.” He started laughing. “I don’t want to be jumped on by lions when I’m 60!” He leaned down and scratched George’s belly, and then said, “I think I’ve come a long way. I don’t need to hug every lion I see.”

Part of the Pride: My Life Among the Big Cats of Africa