When Did Humans Come to the Americas?

Recent scientific findings date their arrival earlier than ever thought, sparking hot debate among archaeologists

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/First-Americans-631.jpg)

For much of its length, the slow-moving Aucilla River in northern Florida flows underground, tunneling through bedrock limestone. But here and there it surfaces, and preserved in those inky ponds lie secrets of the first Americans.

For years adventurous divers had hunted fossils and artifacts in the sinkholes of the Aucilla about an hour east of Tallahassee. They found stone arrowheads and the bones of extinct mammals such as mammoth, mastodon and the American ice age horse.

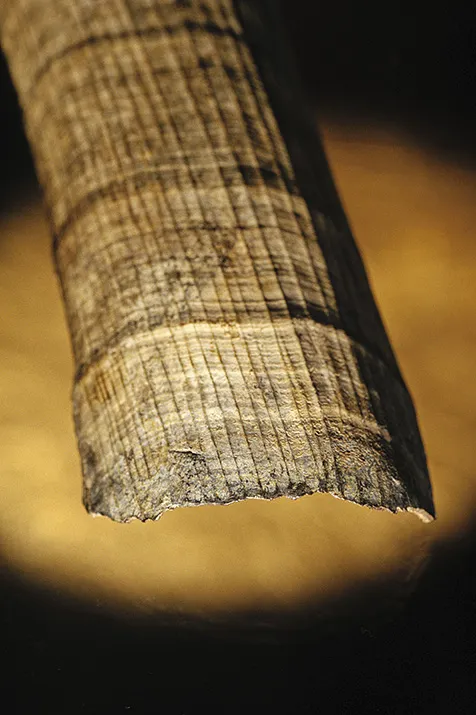

Then, in the 1980s, archaeologists from the Florida Museum of Natural History opened a formal excavation in one particular sink. Below a layer of undisturbed sediment they found nine stone flakes that a person must have chipped from a larger stone, most likely to make tools and projectile points. They also found a mastodon tusk, scarred by circular cut marks from a knife. The tusk was 14,500 years old.

The age was surprising, even shocking, for it suddenly made the Aucilla sinkhole one of the earliest places in the Americas to betray the presence of human beings. Curiously, though, scholars largely ignored the discoveries of the Aucilla River Prehistory Project, instead clinging to the conviction that America’s earliest settlers arrived more recently, some 13,500 years ago. But now the sinkhole is getting a fresh look, along with several other provocative archaeological sites that show evidence of an earlier human presence in the Americas, perhaps much earlier.

Which is why I found myself on the banks of the Aucilla with Michael Waters, director of the Center for the Study of the First Americans at Texas A&M University. A tall, unassuming 57-year-old, with an easy confidence honed during more than 30 years in the field, he had organized archaeologists and divers to gather more evidence of the sinkhole’s role in prehistory. “This site is as old as anything in North America,” Waters said. “The context is fine, and the dating is fine, but people just looked at it and said, ‘Hmm, that’s interesting,’ and that was it. It had a lot of potential, but it was in limbo. We’re here to confirm the earlier work, and if we’re lucky, we’ll find some more artifacts.”

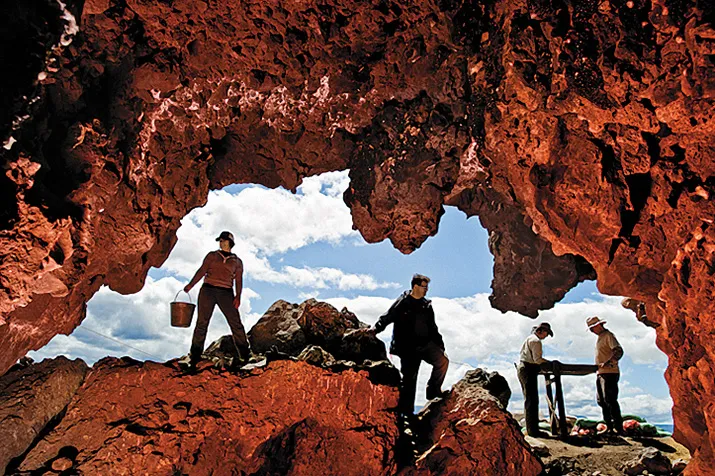

Waters’s team, led by Texas A&M underwater archaeologist Jessi Halligan, worked at the Page-Ladson sink, named for Buddy Page, who discovered it, and John Ladson, the property’s owner. The sink lies 30 feet below the opaque surface of the Aucilla, which, following heavy rains, was dyed nearly black by humus from the hardwood hammock. Fish were jumping in the water, while birds, turtles and the occasional gator patrolled nearby. Were it not for Halligan’s divers, there would be no human presence and the silence would be absolute.

Underwater archaeological sites are staked out and marked in meter-square quadrants, just like open-air excavations. The mud, troweled away by one diver, was fed into the mouth of a four-inch suction dredge held by a second diver. The dredge discharged into a pair of mesh screens mounted on a skiff moored in midstream. Big pieces—stones, bones, leaves and perhaps human artifacts—collected on the top screen, a quarter-inch mesh, and the small stuff was caught by the sixteenth-inch mesh below.

First the researchers had to clear the site of the detritus that had accumulated in the 15 years since the first excavation ended. Then, to reach the most promising level, divers removed a ten-foot layer of clay that overlay it. The work was tedious—“like diving in dark roast coffee,” said James Dunbar, an archaeologist and member of the original Aucilla team who’d returned for a second look—but the blanket of sediment guaranteed the site’s integrity. Everything below the sediment was as old as the people who left it there. In the oxygen-deprived deposits within the Aucilla mud, nothing decays.

Working in the Stygian gloom with lamps and suction pumps, the divers unearthed a number of small bone fragments, the fist-size vertebra of a large mammal and a manhole cover-size shoulder blade that might have belonged to the same mastodon whose tusk bore the cut marks of the ancient hunters. Also recovered in the fine-mesh screen were many pounds of mastodon digesta, the remains of vegetation that the six-ton beast ground to a mulch-like texture and swallowed.

The observations the researchers made in their days at the sinkhole validated the original excavation. (And on a subsequent expedition they found more mastodon bones.) Each new discovery generated fresh enthusiasm. “All we need now,” said Halligan, “are more human artifacts.”

***

About 100,000 years ago, modern human beings started spreading out from their initial homeland in Africa to occupy Europe, Asia and, by sea, even Australia, displacing or absorbing Neanderthals and other archaic hominid species. That diaspora took about 70,000 years, and when it was completed our ancestors stood triumphant.

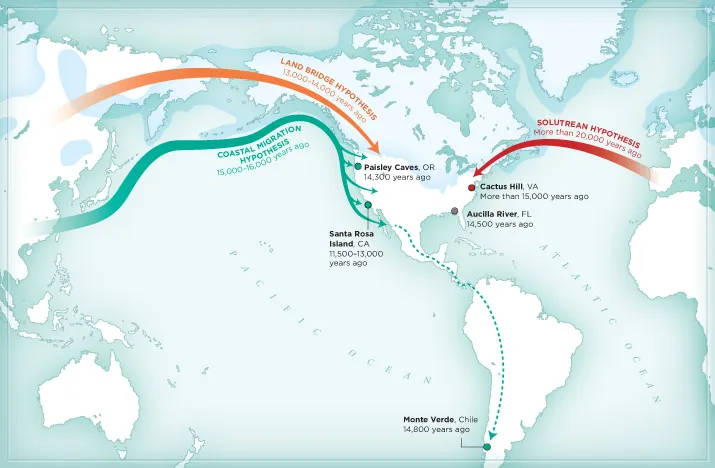

The peopling of the Americas, scholars tend to agree, happened sometime in the past 25,000 years. In what might be called the standard view of events, a wave of big game hunters crossed into the New World from Siberia at the end of the last ice age, when the Bering Strait was a land bridge that had emerged after glaciers and continental ice sheets froze enough of the world’s water to lower sea level as much as 400 feet below what it is today.

The key question is precisely when the migration occurred. To be sure, there were constraints imposed by North America’s glacial history. Researchers suggest that it happened sometime after gradual warming began 25,000 years ago during the depths of the ice age, but well before a severe cold snap reversed the trend 12,900 years ago. Early in this window, when the weather was very cold, migration by boat was more likely because immense expanses of ice would have turned an overland journey into a nightmarish ordeal. Later, however, the ice receded, opening up plausible land bridges for trekkers coming across the Bering Strait.

For decades the most compelling evidence of this standard view consisted of distinctive, exquisitely crafted, grooved bifacial projectile points, called “Clovis points” after the New Mexico town near where they were first discovered in 1929. With the aid of radiocarbon dating in the 1950s, archaeologists determined that the Clovis sites were 13,500 years old. This came as little surprise, for the first Clovis points were found in ancient campsites along with the remains of mammoth and ice age bison, creatures that researchers knew had died out thousands of years ago. But the discovery dramatically undermined the prevailing wisdom that human beings and these ice age “megafauna” did not exist in America at the same time. Scholars flocked to New Mexico to see for themselves.

The idea that the Clovis people, as they came to be known, were the first Americans quickly won over the research community. “The evidence was unequivocal,” said Ted Goebel, a colleague of Waters at the Center for the Study of the First Americans. Clovis sites, it turned out, were spread all over the continent, and “there was a clear association of the fauna with hundreds, if not thousands, of artifacts,” Goebel said. “Again and again it was the full picture.”

Furthermore, the earliest Clovis dates corresponded roughly to the right geological moment—after the ice age warming, before the great cold snap. The northern ice had receded far enough so incoming settlers could curl around to the eastern slope of North America’s coastal mountains and hike south along an ice-free corridor between the cordilleran mountain glaciers to the west and the huge Laurentide ice sheet that swaddled much of Canada to the east. “It was a very nice package, and that’s what sealed the deal,” Goebel said. “Clovis as the first Americans became the standard, and it’s really a high bar.”

When they reached the temperate prairies, the migrants found an environment far different from what we know today—both fantastic and terrifying. There were mammoths, mastodons, giant sloths, camels, bison, lions, saber-toothed cats, cheetahs, dire wolves weighing 150 pounds, eight-foot beavers and short-faced bears that stood more than six feet tall on all fours and weighed 1,800 pounds. Clovis points, finely made and strong, were well suited for hunting large animals.

The hunters spread through the United States and Mexico, the story went, pursuing prey until too few animals remained to support them in the last cold snap. Radiocarbon dates show that most of the megafauna became extinct around 12,700 years ago. The Clovis points disappeared then as well, perhaps because there were no longer any large animals to hunt.

The Clovis theory, over time, acquired the force of dogma. “We all learned it as undergraduates,” Waters recalled. Any artifacts that scholars said came before Clovis, or competing theories that cast doubt on the Clovis-first idea, were ridiculed by the archaeological establishment, discredited as bad science or ignored.

Take South America. In the late 1970s, the U.S. archaeologist Tom D. Dillehay and his Chilean colleagues began excavating what appeared to be an ancient settlement on a creek bank at Monte Verde, in southern Chile. Radiocarbon readings on organic material collected from the ruins of a large tent-like structure showed that the site was 14,800 years old, predating Clovis finds by more than 1,000 years. The 50-foot-long main structure, made of wood with a hide roof, was divided into what appeared to be individual spaces, each with a separate hearth. Outside was a second, wishbone-shaped structure that apparently contained medicinal plants. Mastodons were butchered nearby. The excavators found cordage, stone choppers and augers and wooden planks preserved in the bog, along with plant remains, edible seeds and traces of wild potatoes. Significantly, though, the researchers found no Clovis points. That posed a challenge: either Clovis hunters went to South America without their trademark weapons (highly unlikely) or people settled in South America even before the Clovis people arrived.

There must have been “people somewhere in the Americas 15,000 or 16,000 years ago, or perhaps as long as 18,000 years ago,” said Dillehay, now at Vanderbilt University.

Of the researchers working sites that seemed to precede Clovis people, Dillehay was singled out for special criticism. He was all but ostracized by Clovis advocates for years. When he was invited to meetings, speakers stood up to denounce Monte Verde. “It’s not fun when people write to your dean and try to get you fired,” he recalled. “And then your grad students try to get jobs and they can’t get jobs.”

The Monte Verde site gained wider acceptance after a panel of well-known archaeologists visited it in 1997 and reached a consensus. Dillehay was pleased that the panel had verified the integrity of his team’s work, “but it was a small group of people,” he said, meaning others in the profession continued to harbor doubts.

Two years later, an independent archaeologist, Stuart Fiedel, denounced Monte Verde’s authenticity in Scientific American Discovering Archaeology. Dillehay “fails to provide even the most basic” information about the locations of “key artifacts” at Monte Verde, Fiedel wrote. “Unless and until numerous discrepancies in the final report are convincingly clarified, this site should not be construed as conclusive proof of a pre-Clovis occupation in South America.”

The skepticism lingers. Gary Haynes, a University of Nevada-Reno anthropologist and a Clovis advocate, is not convinced. “There are only a few artifacts, and no flakes,” he said of Monte Verde, citing some of Fiedel’s arguments. “There are a lot of things that have been interpreted as artifacts but don’t look like them. Many of the things may not be the same age, because it is difficult to know exactly where they were found in the site.”

Dillehay rebuffs the criticisms: “More than 1,500 pages were published on Monte Verde, which is five times more than were ever written on any other site in the Americas, including Clovis. All of the artifacts came from the same surface covered by the peat bog and they all made sense in terms of the site’s activities. The vast majority are flaked pebble tools, typical of South American unifacial technologies. North Americans impose their evaluations on South America without even knowing the data down south.” He went on, “Now the field has moved on, and there are numerous pre-Clovis sites that have come to the forefront.”

***

At the Buttermilk Creek Complex archaeological site north of Austin, Texas, in a layer of earth beneath a known Clovis excavation, researchers led by Waters over the past several years found 15,528 pre-Clovis artifacts—most of them toolmaking chert flakes, but also 56 chert tools. Using optically stimulated luminescence, a technique that analyzes light energy trapped in sediment particles to identify the last time the soil was exposed to sunlight, they found that the oldest artifacts dated to 15,500 years ago—some 2,000 years older than Clovis. The work “confirms the emerging view that people occupied the Americas before Clovis,” the researchers concluded in Science in 2011. In Waters’ view, the people who made the oldest artifacts were experimenting with stone technology that, over time, may have developed further into Clovis-style tools.

Waters recently landed other blows to the Clovis orthodoxy in collaboration with Thomas Stafford, president of the Colorado-based Stafford Research Laboratories. In one series of experiments using accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS), a dating technique that is more precise than earlier radiocarbon measurements, they reanalyzed a mastodon rib from a skeleton previously recovered in Manis, Washington, and found to have a projectile point lodged in it. The original radiocarbon tests had surrounded the discovery in controversy because they showed it to be 13,800 years old—centuries older than Clovis. The new AMS tests confirmed that age estimate date, and DNA analysis showed that the projectile point was mastodon bone.

Deploying AMS technology, Waters and Stafford also retested many known Clovis samples from around the country, some collected decades earlier. The results, Waters said, “blew me away.” Instead of a culture spanning about 700 years, the analysis shrunk the Clovis window to 13,100 to 12,800 years ago. This new time frame required the Siberian hunters to negotiate the ice-free corridor, settle two continents and put the megafauna on the road to extinction within 300 years, an incredible feat. “Not possible,” Waters said. “You’ve got people in South America at the same time as Clovis, and the only way they could have gotten down there that fast is if they transported like ‘Star Trek.’ ”

But Haynes, of the University of Nevada-Reno, disagrees. “Think of a small number of very mobile people covering a lot of ground,” he suggests. “They could have been walking thousands of kilometers per year.”

Goebel, of the Texas A&M Center for the Study of the First Americans, characterizes his attitude toward pre-Clovis finds as “acceptance with reservation.” He said he’s disturbed by “nagging” shortcomings. Each of the older sites appears to be one-of-a-kind, he said, without a “demonstrated pattern across a region.” With Clovis, he adds, it is clear that the original sites were part of something bigger. The absence of a consistent pre-Clovis pattern “is one of the things that has hung up a lot of people, including myself.”

***

The discovery of numerous artifacts that pre-date Clovis has, over the years, required scholars to come up with different ideas about not only when people arrived in the Americas but how they got here. For instance, if they were already established 14,800 years ago, they must not have used the famed ice-free corridor through North America: Researchers say that it would not appear for another 1,000 years.

Maybe the first Americans didn’t walk here but came in small boats and followed the coastline, some researchers say. That possibility was first suggested in the 1950s with the discovery of Clovis-era human bones—but no artifacts—on Santa Rosa Island in the Santa Barbara Channel off the California coast. Over the past decade, though, a joint University of Oregon-Smithsonian team of archaeologists unearthed dozens of stemmed and barbed projectile points from Santa Rosa and other Channel Islands, along with the remains of fish, shellfish, seabirds and seals. Radiocarbon dates showed much of the organic material was about 12,000 years old, roughly within the Clovis time frame.

The findings do not prove that the continent’s first settlers came by sea, of course. The islands were only about four miles offshore at the time, and could have been visited by people who’d settled on the mainland. Still, the sites establish that these island dwellers were seafarers of a sort and accustomed to a seafood diet.

Jon Erlandson, a University of Oregon archaeologist, and Torben Rick, an anthropologist at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, propose a pre-Clovis “kelp highway” for coast-hugging seamen skirting the southern edge of the Bering land bridge on their way from northeast Asia to the New World. “People came between 15,000 and 16,000 years ago” by sea, and “could eat the same seaweed and seafood as they moved along the coastline in boats,” Erlandson said. “It seems logical.” The notion that ancient people could travel great distances by boat isn’t far-fetched; many anthropologists believe that humans voyaged from the Asian mainland to Australia 45,000 years ago.

Though Erlandson said he’s convinced that the Clovis people were not the first in the Americas, he acknowledged that definitive proof of a pre-Clovis coastal route may never be found: Whatever beach settlements existed in those days of especially low sea level were long ago submerged or swept away by Pacific tides.

Moreover, the Channel Islands projectiles have nothing in common with Clovis points, as Erlandson pointed out. They appear to be related to a different toolmaking approach called the western stemmed tradition; featuring stems of different shapes that attach the projectile points to spears or darts, they were prevalent in the Pacific Northwest and the Great Basin. And they do not have the fluting characteristic of Clovis. Those observations strengthen the view that other tool-making human cultures were present in the Americas at the same time as the Clovis people, and in all likelihood beforehand as well.

The link between the Channel Islands artifacts and the western stemmed tradition recently acquired greater significance: Inside the Paisley Caves in Oregon, scientists excavated similar points that were associated with organic material yielding radiocarbon dates 13,000 years old—contemporary with Clovis.

The University of Oregon’s Dennis L. Jenkins, who led the Paisley excavation, re-examined a site first explored in the 1930s. The earlier documentation (photographs and some film) was insufficient to show a definite association between the bones and artifacts. But soon, he said, “we had artifacts and we had the bones” from the site. To determine if the human artifacts were the same age as the animal remains, the researchers conducted radiocarbon dating tests on human coprolites—petrified feces—extracting carbon residue from the organic material digested long ago. They also analyzed human mitochondrial DNA in the sample, probably shed from the intestinal wall, and determined that it came from a modern human with an apparently Asian genome. The toolmakers had lived 13,000 years ago.

“And there is nothing connecting this to any Clovis site,” Jenkins said. “You have two technologies existing at the same time in North America, and there is no direct immediate relationship.”

To answer critics, Jenkins and his team tested the DNA of project participants, to make sure they had not contaminated the coprolites, and tested the sediments surrounding the coprolites for modern rodent urine and other telltale signs the area had been tainted. They found no evidence of contemporary animal or human DNA.

Jenkins and his colleagues published the final results this year and closed the site: “We’ve gotten to the bottom,” he said. “We’ve convinced the people who are willing to be convinced that the caves are as old as Clovis, if not older.”

***

Perhaps the most radical scholarly work suggests the Americas were colonized first by immigrants from Europe several thousand years before Clovis. The theory is the brainchild of Dennis Stanford, a curator of North American archaeology at the National Museum of Natural History, and Bruce Bradley, an archaeologist at Britain’s University of Exeter. In their 2012 book Across Atlantic Ice, they suggest that these Europeans reached the New World more than 20,000 years ago, settled in the eastern United States, developed the Clovis technology over several thousand years, then spread across the continent.

This theory is based partly on similarities between Clovis points and finely crafted “laurel leaf” points from Europe’s Solutrean culture, which flourished in southwestern France and northern Spain between 24,000 and 17,000 years ago. Stanford and Bradley argue that artifacts found at Page-Ladson, as well as other pre-Clovis sites, including the Meadowcroft Rock Shelter in western Pennsylvania and the sand dunes of Cactus Hill in southeastern Virginia, have similarities to Solutrean technologies.

The Solutreans, whose territory on the European continent was apparently rather compact, may have been forced by encroaching glaciers and extreme cold to cluster on the Atlantic coast. At some point, Stanford and Bradley say, the stresses of overpopulation may have forced some Solutreans to escape by sea. They headed north and west beneath the Atlantic ice sheet to nudge into North America at the Grand Banks of Newfoundland.

Stanford and Bradley say evidence for the Solutreans’ presence in America includes stone artifacts gathered by archaeologists at several sites on the eastern shore of Chesapeake Bay, all producing dates more than 20,000 years old. Most of the dates were derived from organic material found with the artifacts. The exception was a mastodon tusk with attached bone and teeth netted by a fisherman in 1974, along with a laurel leaf-shaped stone knife. Stanford found the tusk to be 22,760 years old. Among other things, the Solutrean hypothesis provides context not only for the Clovis people, but also for North America’s pre-Clovis sites. And it does not rule out Bering Sea migrations—those could have happened, too.

“Solutrean evolved into Clovis over close to 13,000 years,” Stanford said, and the Clovis hunters began migrating westward when the cold snap brought dry, windy, inhospitable weather to the East Coast.

But the archaeological evidence found so far in support of a European migration more than 20,000 years ago has raised skepticism. And as is the case with the kelp highway, many sites that could prove or disprove the hypothesis are now underwater. Dillehay said he had found the idea of an Atlantic crossing worthy of further investigation, even though “the hard evidence is not yet there.”

Waters, of Texas A&M, is skeptical. “I’m looking for clean evidence,” he said. “We’re past ‘Clovis first,’ and we’re developing a new model. You read the literature and you use your imagination, but then you have to go out and find the empirical evidence to support your hypothesis.”

None of the doubts expressed by critics have stopped Stanford and Bradley, veterans of the Clovis wars, from pushing forward. “Solutrean people became more and more efficient in exploiting the rich sea margin resources,” they write in Across Atlantic Ice. “Eventually their range expansion led them to a whole new world in the west.”

***

These days Waters says his research focuses on pre-Clovis or likely pre-Clovis sites where more information can be obtained. Unlike many of his colleagues, Waters isn’t captive to peer reviewers at granting agencies; the Center for the Study of the First Americans also has its own funding. “In the past you’d propose something and send it out for review, and the Clovis people would shoot it down,” he said.

It was against the backdrop of renewed enthusiasm for findings predating Clovis settlements that Waters reopened the Page-Ladson site on the Aucilla River. For Waters, the debate about Clovis “is finished,” he said over breakfast one morning in Perry, Florida, before we went out to the Aucilla site. “The objective everywhere we go is to learn more about pre-Clovis by doing good science. I’m investigating the first Americans.” If some folks don’t want to believe it, he added, “that’s up to them.”