Why I Take Fake Pills

Surprising new research shows that placebos still work even when you know they’re not real

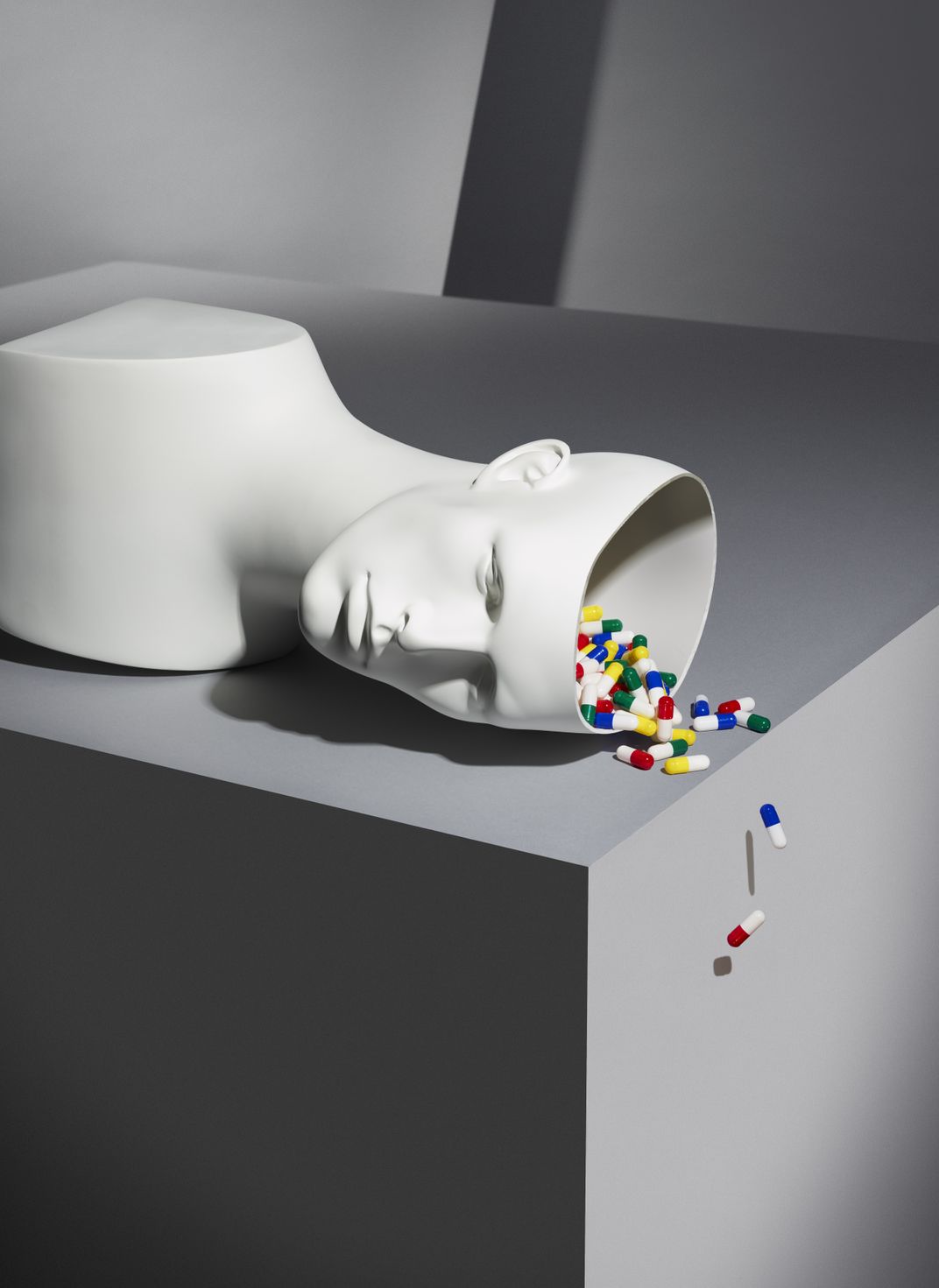

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/fe/d1fed003-33c4-4585-8968-cbd194c65bf8/istock-168763163.jpg)

So here they are,” John Kelley said, taking a paper bag off his desk and pulling out a big amber pill bottle. He looked momentarily uncertain. “I don’t really know how to do this,” he admitted.

“Just hand them over,” I said.

“No, the way we do this is important.”

I’ve known Kelley for decades, ever since we were undergrads together. Now he’s a psychology professor at Endicott College and the deputy director of PiPS, Harvard’s Program in Placebo Studies and Therapeutic Encounter. It’s the first program in the world devoted to the interdisciplinary study of the placebo effect.

The term “placebo” refers to a dummy pill passed off as a genuine pharmaceutical, or more broadly, any sham treatment presented as a real one. By definition a placebo is a deception, a lie. But doctors have been handing out placebos for centuries, and patients have been taking them and getting better, through the power of belief or suggestion—no one’s exactly sure. Even today, when the use of placebos is considered unethical or, in some cases, illegal, a survey of 679 internists and rheumatologists showed that about half of them prescribe medications such as vitamins and over-the-counter painkillers primarily for their placebo value.

For Kelley—a frustrated humanist in the increasingly biomedical field of psychology—the placebo effect challenges our narrow focus on pills. “I was in grad school training as a psychotherapist,” he told me once, “and I came across a study arguing that antidepressants work just as well as psychotherapy. I didn’t mind that so much, because I like psychotherapy and see its value. But later I found another study showing that antidepressants actually work no better than placebos, and that definitely bothered me. Did this mean that psychotherapy was nothing but a placebo? It took me quite a while to consider the reverse, that placebo is a form of psychotherapy. It’s a psychological mechanism that can be used to help people self-heal. That’s when I knew I wanted to learn more.”

There’s one more strange twist: The PiPS researchers have discovered that placebos seem to work well when a practitioner doesn’t even try to trick a patient. These are called “open label” placebos, or placebos explicitly prescribed as placebos.

That’s where I come in: By the time I arrived at Kelley’s office, I’d been working with him for about a month, designing an unofficial one-man open-label placebo trial with the goal of getting rid of my chronic writer’s block and the panic attacks and insomnia that have always come along with it.

“I think we can design a pill for that,” he’d told me initially. “We’ll fine-tune your writing pill for maximum effectiveness, color, shape, size, dosage, time before writing. What color do you associate with writing well?”

I closed my eyes. “Gold.”

“I’m not sure the pharmacist can do metallic. It may have to be yellow.”

Over the next few weeks, we’d discussed my treatment in greater detail. Kelley had suggested capsules rather than pills, as they would look more scientific and therefore have a stronger effect. He’d also wanted to make them short-acting: He believed a two-hour time limit would cut down on my tendency to procrastinate. We’d composed a set of instructions that covered not only how to take them but what exactly they were going to do to me. Finally, we’d ordered the capsules themselves, which cost a hefty $405, though they contained nothing but cellulose. Open-label placebos are not covered by insurance.

Kelley reassured me. “The price increases the sense of value. It will make them work better.”

I called the pharmacy to pay with my credit card. After the transaction the pharmacist said to me, “I’m supposed to counsel customers on the correct way to take their medications, but honestly, I don’t know what to tell you about these.”

“My guess is that I can’t overdose.”

“That’s true.”

“But do you think I could get addicted?”

“Ah, well, it’s an interesting question.”

We laughed, but I felt uneasy. Open label had started to feel like one of those postmodern magic shows in which the magician explains the illusion even as he performs the trick—except there was no magician. Everyone was making it up as they went along.

**********

Kelley’s office is full of placebo gags. On his desk sits a clear plastic aspirin bottle labeled To cure hypochondria, and on the windowsill are a couple of empty wine bottles marked Placebo and Nocebo, the term for negative effects induced by suggestion, placebo’s dark twin.

One of the key elements of the placebo effect is the way our expectations shape our experience. As he handed over the pills, Kelley wanted to heighten my “expectancy,” as psychologists call it, as much as possible. What he did, finally, was show me all the very official-looking stuff that came with the yellow capsules: the pill bottle, the label, the prescription, the receipt from the pharmacy, and the instruction sheet we had written together, which he read to me out loud. Then he asked if I had any questions.

Suddenly we were in the midst of an earnest conversation about my fear of failure as a writer. There was something soothing about hearing Kelley respond, with his gentle manner. As it turned out, that’s another key element of the placebo effect: an empathetic caregiver. The healing force, or whatever we are going to call it, passes through the placebo, but it helps if it starts with a person, someone who wants you to get better.

Back home, I sat down at the dining room table with a glass of water and an open notebook. “Take 2 capsules with water 10 minutes before writing,” said the label. Below that: “Placebo, no refills.”

I unfolded the directions:

This placebo has been designed especially for you, to help you write with greater freedom and more spontaneous and natural feeling. It is intended to help eliminate the anxiety and self-doubt that can sometimes act as a drag on your creative self-expression. Positive expectations are helpful, but not essential: It is natural to have doubts. Nevertheless, it is important to take the capsules faithfully and as directed, because previous studies have shown that adherence to the treatment regimen increases placebo effects.

I swallowed two capsules, and then, per the instructions, closed my eyes and tried to explain to the pills what I wanted them to do, a sort of guided meditation. I became worried that I wouldn’t be able to suspend disbelief long enough to let the pills feel real to me. My anxieties about their not working might prevent them from working.

Over the next few days, I felt my anxiety level soar, especially when filling out the self-report sheets. On a scale of 0-10, where 0 is no anxiety and 10 is the worst anxiety you have ever experienced, please rate the anxiety you felt during the session today. I was giving myself eights out of a misplaced sense of restraint, though I wanted to give tens.

Then, one night in bed, my eyes opened. My heart was pounding. The clock said 3 a.m. I got up and sat in an armchair and, since my pill bottle was there on the desk, took two capsules, just to calm down. They actually made me feel a little better. In the morning I emailed Kelley, who wrote back saying that, like any medication, the placebo might take a couple of weeks to build up to a therapeutic dose.

**********

Ted Kaptchuk, Kelley’s boss and the founder and director of PiPS, has traveled an eccentric path. The child of a Holocaust survivor, he became embroiled in radical politics in the 1960s and later studied Chinese medicine in Macao. (“I needed to find something to do that was more creative than milking goats and not so destructive as parts of the antiwar movement.”) After returning to the U.S., he practiced acupuncture in Cambridge and ran a pain clinic before being hired at Harvard Medical School. But he’s not a doctor and his degree from Macao isn’t even recognized as a PhD in the state of Massachusetts.

Kaptchuk’s outsider status has given him an unusual amount of intellectual freedom. In the intensely specialized world of academic medicine, he routinely crosses the lines between clinical research, medical history, anthropology and bioethics. “They originally hired me at Harvard to do research in Chinese medicine, not placebo,” he told me, as we drank tea in his home office. His interests shifted when he tried to reconcile his own successes as an acupuncturist with his colleagues’ complaints about the lack of hard scientific evidence. “At some point in my research I asked myself, ‘If the medical community assumes that Chinese medicine is “just” a placebo, why don’t we examine this phenomenon more deeply?’”

Some studies have found that when acupuncture is performed with retractable needles or lasers, or when the pricks are made in the wrong spots, the treatment still works. By conventional standards, this would make acupuncture a sham. If a drug doesn’t outperform a placebo, it’s considered ineffective. But in the acupuncture studies, Kaptchuk was struck by the fact that patients in both groups were actually getting better. He points out that the same is true of many pharmaceuticals. In experiments with postoperative patients, for example, prescription pain medications lost half their effectiveness when the patient did not know that he or she had just been given a painkiller. A study of the migraine drug rizatriptan found no statistical difference between a placebo labeled rizatriptan and actual rizatriptan labeled placebo.

What Kaptchuk found was something akin to a blank spot on the map. “In medical research, everyone is always asking, ‘Does it work better than a placebo?’ So I asked the obvious question that nobody was asking: ‘What is a placebo?’ And I realized that nobody ever talked about that.”

To answer that question, he looked back through history. Benjamin Franklin’s encounter with the charismatic healer Franz Friedrich Anton Mesmer became a sort of paradigm. Mesmer treated patients in 18th-century Paris with an invisible force he called “animal magnetism.” Franklin used an early version of the placebo trial to prove that animal magnetism wasn’t a real biological force. Franklin’s one mistake, Kaptchuk believed, was to stop at discrediting Mesmer, rather than going on to understand his methods. His next question should have been: “How does an imaginary force make sick people well?”

Kaptchuk sees himself as picking up where Franklin left off. Working with Kelley and other colleagues, he’s found that the placebo effect is not a single phenomenon but rather a group of inter-related mechanisms. It’s triggered not just by fake pharmaceuticals but by the symbols and rituals of health care itself—everything from the prick of an injection to the sight of a person in a lab coat.

And the effects are not just imaginary, as was once assumed. Functional MRI and other new technologies are showing that placebos, like real pharmaceuticals, actually trigger neurochemicals such as endorphins and dopamine, and activate areas of the brain associated with analgesia and other forms of symptomatic relief. As a result of these discoveries, placebo is beginning to lose its louche reputation.

“Nobody would believe my research without the neuroscience,” Kaptchuk told me. “People ask, ‘How does placebo work?’ I want to say by rituals and symbols, but they say, ‘No, how does it really work?’ and I say, ‘Oh, you know, dopamine’—and then they feel better.” For that reason, PiPS has begun sponsoring research in genetics as well.

After meeting with Kaptchuk, I went across town to the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital to see the geneticist Kathryn Tayo Hall. Hall studies the gene for Catechol-O-methyltransferase (also called COMT), an enzyme that metabolizes dopamine. In a study of patients being treated for irritable bowel syndrome, she found a strong relationship between placebo sensitivity and the presence of a COMT enzyme variant associated with higher overall levels of dopamine in the brain. She also found a strong relationship between placebo insensitivity and a high-activity form of the COMT enzyme variant associated with lower dopamine levels. In other words, the type of COMT enzyme these patients possessed seemed to determine whether a placebo worked for them or not.

Is COMT “the placebo gene”? Hall was quick to put her findings in context. “The expectation is that the placebo effect is a knot involving many genes and biosocial factors,” she told me, not just COMT.

There is another layer to this, Hall pointed out: Worriers, people with higher dopamine levels, can exhibit greater levels of attention and memory, but also greater levels of anxiety, and they deal poorly with stress. Warriors, people with lower dopamine levels, can show lesser levels of attention and memory under normal conditions, but their abilities actually increase under stress. The placebo component thus fits into the worrier/warrior types as one might expect: Worriers tend to be more sensitive to placebos; warriors tend to be less sensitive.

In addition to being a geneticist, Hall is a documentary filmmaker and a painter. We sat in her office beneath a painting she had done of the COMT molecule. I told her, a little sheepishly, about my one-man placebo trial, not sure how she would react.

“Brilliant,” she said, and showed me a box of homeopathic pills she takes to help with pain in her arm from an old injury. “My placebo. The only thing that helps.”

**********

What might the future of placebo look like? Kaptchuk talks about doctors one day prescribing open-label placebos to their patients as a way of treating certain symptoms, without all the costs and side effects that can come with real pharmaceuticals. Other researchers, including those at the National Institute of Mental Health, are focusing on placebo’s ability to help patients with hard-to-treat symptoms, such as nausea and chronic pain. Still others talked about using the symbols and rituals of health care to maximize the placebo component of conventional medical treatments.

Hall would like to see placebo research lead to more individualized medicine; she suggests that isolating a genetic marker could allow doctors to tailor treatment to a patient’s individual level of placebo sensitivity. Kelley, for his part, hopes that placebo research might refocus our attention on the relationship between patient and caregiver, reminding us all of the healing power of kindness and compassion.

Two weeks after returning home from Boston, the writing capsules seemed to kick in. My sentences were awkward and slow, and I disliked and mistrusted them as much as ever, but I did not throw them out: I did not want to admit to that in the self-reports I was keeping, sheets full of notes like “Bit finger instead of erasing.” When the urge to delete my work became overwhelming, I would grab a couple of extra capsules and swallow them (I was way, way over my dosage—had in fact reached Valley of the Dolls levels of excess). “I don’t have to believe in you,” I told them, “because you’re going to work anyway.”

One night, my 12-year-old daughter began having trouble sleeping. She was upset about some things happening with the other kids in school; we were talking about it, trying to figure out how best to help, but in the meantime she needed to get some rest.

“Would you like a placebo?” I asked.

She looked interested. “Like you take?”

I got my bottle and did what John Kelley had done for me in his office at Endicott, explaining the scientific evidence and showing her the impressive label. “Placebo helps many people. It helped me, and it will help you.” She took two of the shiny yellow capsules and within a couple of minutes was deeply asleep.

Standing in the doorway, I shook two more capsules into the palm of my hand. I popped them into my mouth and went back to work.

Related Reads

Cure: A Journey into the Science of Mind Over Body