Adorable Portraits Put Nocturnal Animals in the Spotlight

A new photo book showcases animals we humans rarely see—while a new study says we may have more in common with night-dwellers than thought

Humans are naturally afraid of the dark, mostly because it can cloak myriad dangers. But take a closer look, and it turns out many of the creatures that go bump in the night are adorable, resourceful and awe-inspiring. Now fossil studies suggest that the very first mammals may have been born into darkness.

Today a wide variety of known animal species are nocturnal, mostly active at night, or crepuscular, mostly active at dawn and dusk. These behaviors offer three main advantages: reduced competition for resources with daytime critters, protection from heat and water loss in arid regions and a way to hide from predators or find unsuspecting prey.

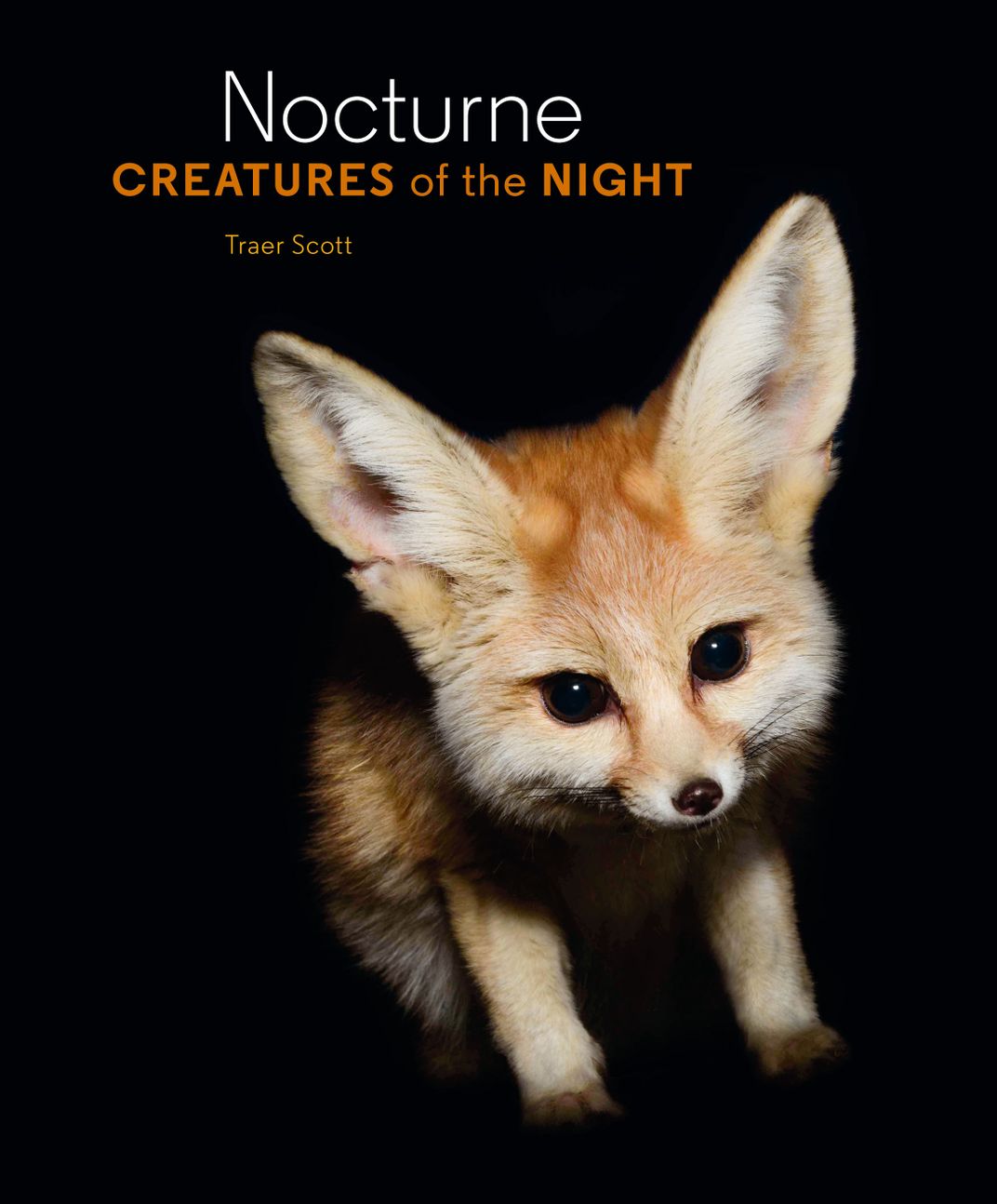

Photographer Traer Scott became fascinated with night-dwellers while watching moths fly near her porch lights on summer evenings—and then thinking about the bats that prey on those moths. In her new book, Nocturne: Creatures of the Night (Princeton Architectural Press, 2014), Traer highlights the diversity of nocturnal species around the world, offering a glimpse at birds, bats, spiders and other animals that most humans rarely see.

While nocturnality makes sense for those animals and many others today, how or why it first emerged has been unclear. One prevailing scientific theory was that nocturnality evolved in early mammals as a defensive strategy to escape the jaws of predatory dinosaurs, which were mostly active during the day. But according to research recently published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, being nocturnal may have been the status quo for the common ancestor of all mammals.

The new finding hinges on an ancient group of reptilian proto-mammals called the synapsids, which arose during the Permian period, some 320 million years ago. Dimetrodon, a massive sail-backed reptile that went extinct 40 million years before the dinosaurs arrived, is probably the most well known synapsid. This group of animals endured throughout the Carboniferous and Jurassic periods before giving rise to the first true mammals some 200 million years ago.

To test the assumption that mammals became nocturnal to avoid becoming dino dinner, researchers from the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago and the W.M. Keck Science Department in California turned to 300-million-year-old synapsid fossils. They analyzed scleral rings, or circular bones that cradle the eyes of some animal groups (you might have encountered them when eating a whole fish, for example). This ridge has disappeared in mammals, but it was present in our synapsid relatives.

In species living today, the size of those rings in relation to the animal’s body size corresponds with eye function and light sensitivity. Just as nocturnal animals today tend to have large eyes, so too would those of the past, the team thinks. They analyzed the eye dimensions and functions of scleral rings from 38 synapsid fossils representing 24 species. Nocturnality, they found, actually has a “surprisingly deep” evolutionary origin, likely evolving in synapsids more than 100 million years before mammals even appeared.

It might be that nocturnality evolved for the exact opposite reason scientists previously assumed, the team says. Breaking down the results, about half of the herbivorous species they analyzed seemed to adhere to a daytime lifestyle, compared to just 6 percent of the carnivores. Nocturnality, in other words, seems to have been a favorite strategy of predators that took advantage of darkness to sneak up on sleeping prey.

Those animals’ ability to operate under the cloak of darkness makes them no less vulnerable to human threats, however. In her book on nocturnal animals, Traer notes that many nocturnal species today are suffering from habitat loss and degradation, including from light pollution:

“Owls, bats, raccoons, and other nocturnal animals with specialized night vision can lose their ability to see properly in heavily light-polluted areas. This decreased vision affects their ability to hunt and forage and can put their lives in immediate danger if they are unable to see approaching predators.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bb/c0/bbc0a392-52f6-4ecb-9f3d-03cf4e9d2712/20_nocturne_indianflyingfox1_p21_p20.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/17/cf/17cff9d9-600b-40ec-849b-06cdba689003/34_nocturne_smallearedgalago_p93_p93.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/33/18/3318a1bb-d459-444a-8f4e-4839ad4f360f/39_nocturne_sugarglider1crop_p105_p105.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)