Gas Shortages in 1970s America Sparked Mayhem and Forever Changed the Nation

Half a century ago, a series of oil crises caused widespread panic and led to profound shifts in U.S. culture

:focal(460x274:461x275)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/de/fd/defd603f-4d86-4606-bb14-2b5952ddf54b/4271715683_18dc8fda1a_c.jpg)

When a ransomware attack forced the Colonial Pipeline system to shut down its network last Friday, panic ensued at gas pumps across the southeastern United States. Anticipating a shortage, drivers lined up to top off their tanks and fill gas canisters to be tucked away in storage. On Wednesday, the United States Consumer Product Safety Commission tweeted the alarming message “Do not fill plastic bags with gasoline.”

The events of the past week echo crises that swept the country in the 1970s, when gas shortages led to demand spikes that only exacerbated the situation.

“We’ve seen this dance before,” writes historian Meg Jacobs, author of Panic at the Pump: The Energy Crisis and The Transformation of American Politics in the 1970s, for CNN. “If you are of a certain age, you surely recall sitting in the back of your family’s station wagon (with no seatbelts of course) waiting hours on end in the 1970s to get a gallon of gas.”

Per the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, the first of the 1970s gas panics began in October 1973, when the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) raised the price of crude oil by 70 percent. That move, together with an embargo on the U.S., was part of Arab countries’ response to the start of the Yom Kippur War (a weeks-long conflict that pitted Egypt and Syria against Israel), but it also reflected simmering tensions between OPEC and U.S. oil companies.

In the three months after the embargo began, History.com explains, local and national leaders called for people to reduce their energy consumption, even suggesting not hanging Christmas lights.

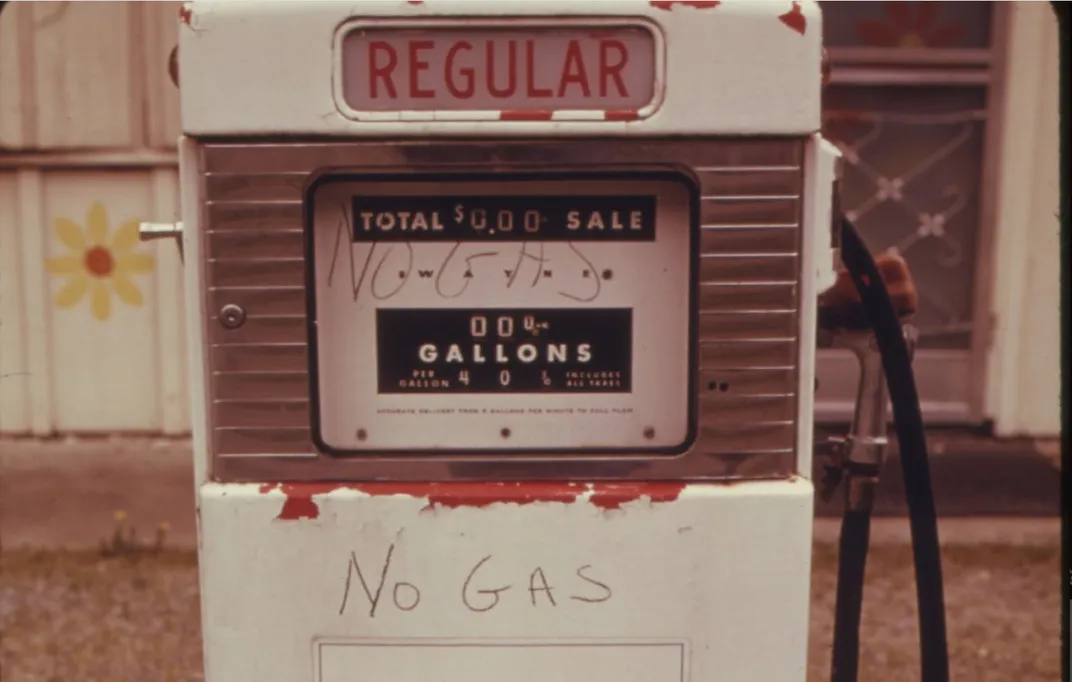

The oil crisis affected everything from home heating to business costs that were passed on to consumers in a range of industries. But the impact was most obvious on the roads. As Greg Myre wrote for NPR in 2012, gas station lines wrapped around blocks. Some stations posted flags—green if they had gas, red if they didn’t and yellow if they were rationing. Some businesses limited how much each customer could buy. Others used odd-even rationing: If the last digit of a car’s license plate was odd, it could only fill up on odd-numbered days.

“The notion that Americans were going run out of gas was both new and completely terrifying,” Jacobs tells the Washington Post’s Reis Thebault. “It came on so suddenly.”

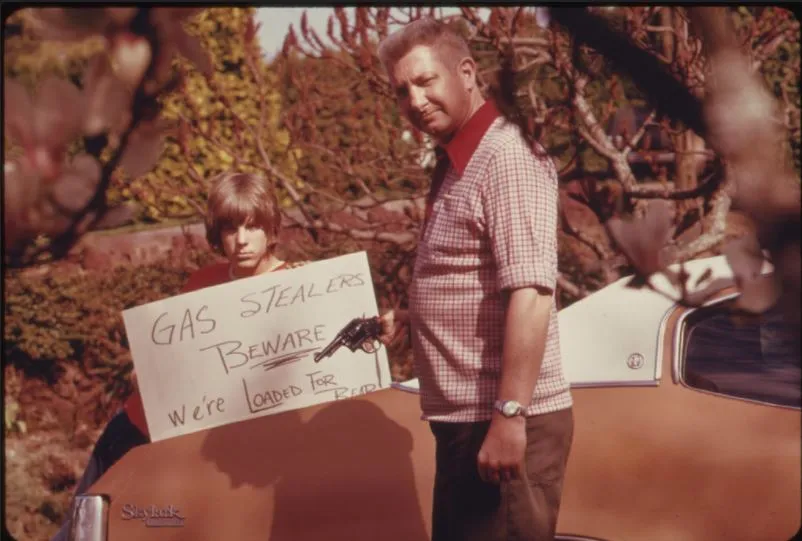

By February 1974, according to the Baltimore Sun’s Mike Klingaman, drivers in Maryland found themselves waiting in five-mile lines. Some stations illegally sold to regular customers only, while others let nurses and doctors jump the line. Fights broke out, and some station owners began carrying guns for self-protection. One man, John Wanken of Cockeysville, described spending a whole morning driving around the city looking for gas but only managing to buy $2 worth—just enough to replenish the half-tank he’d burned during the four hours of driving.

“It’s turning us into animals,” Wanken said. “It’s back to the cavemen.”

Per the U.S. State Department, apparent progress in negotiations between Israel and Syria convinced OPEC to lift the embargo in March 1974. But as Lucas Downey notes for Investopedia, the Iranian Revolution sparked a new oil shock five years later, in 1979. Gas lines, panic buying and rationing returned. According to Jacobs, residents of Levittown, Pennsylvania, rioted, throwing rocks and beer bottles at police and setting two cars on fire while chanting “More gas! More gas!”

“Americans’ fear turned a small interruption in supply into a major crisis,” explains Jacobs. “In truth, the major oil companies were able to shift around distribution in ways that should have minimized the impact in the 1970s. But panic took hold, and the rush to tank up compounded the situation.”

The oil crises of the ’70s led to profound changes in the nation. The love of huge cars that had burned through the 1950s and ’60s cooled: In December 1973, for instance, a Time magazine cover announced “The Big Car: End of the Affair.” (Previously, Jacobs tells the Post, “Everybody was completely dependent and in love with their cars as a symbol of American triumph and freedom.”) In 1974, President Richard Nixon signed the first national speed limit, restricting travel on interstate roads to 55 miles per hour. And, in 1975, the federal government created the Strategic Petroleum Reserve and set its first fuel economy standards for the auto industry.

As Michael L. Ross, a political scientist at the University of California’s Institute of Environment and Sustainability, wrote for the Guardian in 2015, average fuel economy for U.S. vehicles rose 81 percent between 1975 and 1988. Bipartisan initiatives ramped up funding for energy and conservation research; federal agencies including NASA began experimenting with wind and solar energy and exploring new technology to make cars more efficient.

Soon after the start of his term in 1977, President Jimmy Carter told the nation that, aside from preventing war, the energy crisis “is the greatest challenge our country will face during our lifetimes.”

Politicians in the 1970s were not overly focused on climate change. Instead, they mistakenly believed that the world was running out of oil. But as Ross pointed out, the moves made in response to the energy crisis had an impact on Earth’s climate. U.S. carbon emissions grew an average of 4.1 percent each year in the decade before 1973. Since then, they’ve risen just 0.2 percent per year, even as the nation’s population has continued to grow.

“The year 1973 became the historic peak year of U.S. per capita emissions: [E]ver since then it has dropped,” Ross wrote. “As a result, the response to the 1970s oil shocks gave the planet a life-saving head start in the struggle to avoid catastrophic climate change.”

It remains to be seen whether the current gas shortages will encourage the country to continue its move away from fossil fuels.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/64/95/64954012-2d20-448e-a25b-437c897f084d/4272453454_41a51c5d2a_k.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)