This Art Show Looks at 500 Years of Failed Utopias

So far, the ideal has yet to work out

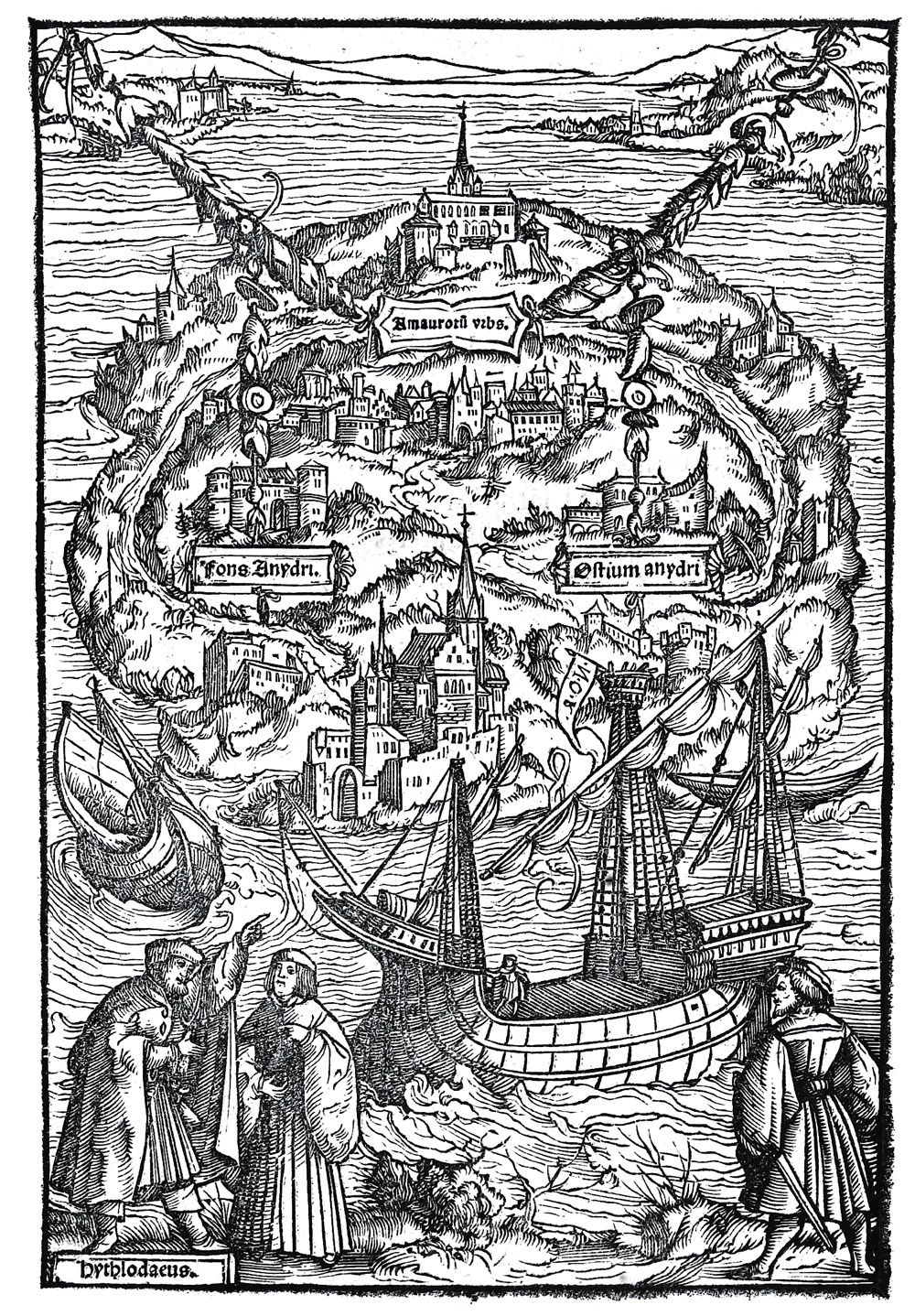

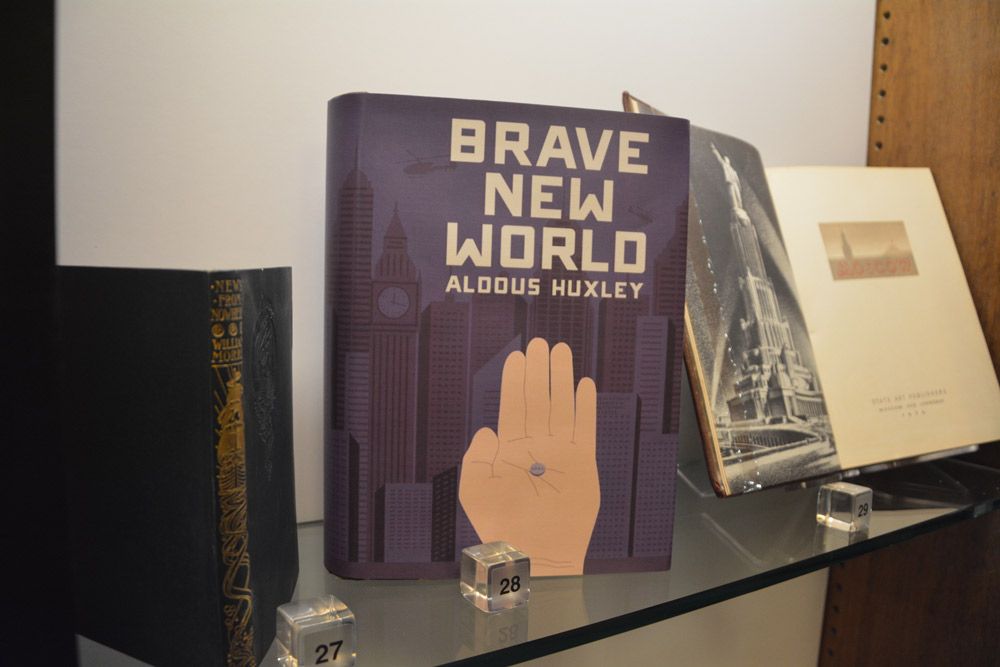

When Thomas More coined the word “utopia” for his eponymous book published in 1516, the word described his ideal city. In the book, More writes Utopia as a city situated on a fictional island in the Atlantic Ocean characterized by a well-oiled and peaceful society. Of course, in the original Greek, the name of More’s perfect country translates to "no place" or "nowhere"—though that hasn’t stopped people from trying to make their own. Now, to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the term, a new exhibit at the University of Southern California Libraries dives into five centuries of failed real-life utopias.

Creating a real-world utopia is much harder than just dreaming up the guidelines for a new society, as USC Libraries curator Tyson Gaskill found when his team sat down to figure out how to look at the history of these searches for perfect societies.

“When we went looking at these different utopias, we all realized that one man’s utopia is another man’s dystopia,” Gaskill tells Smithsonian.com. “None of these utopias sound great.”

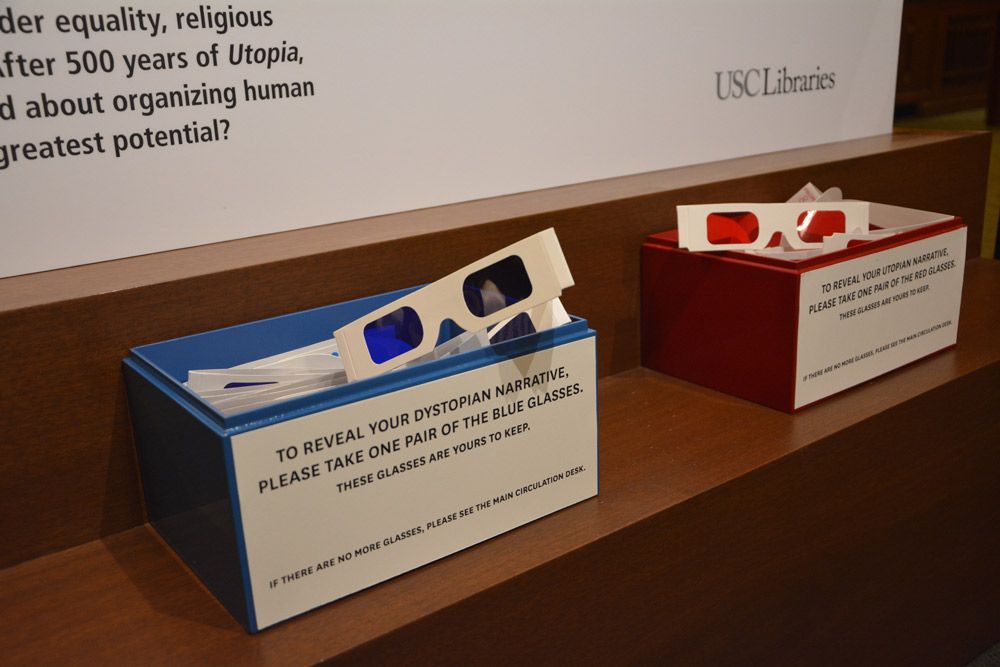

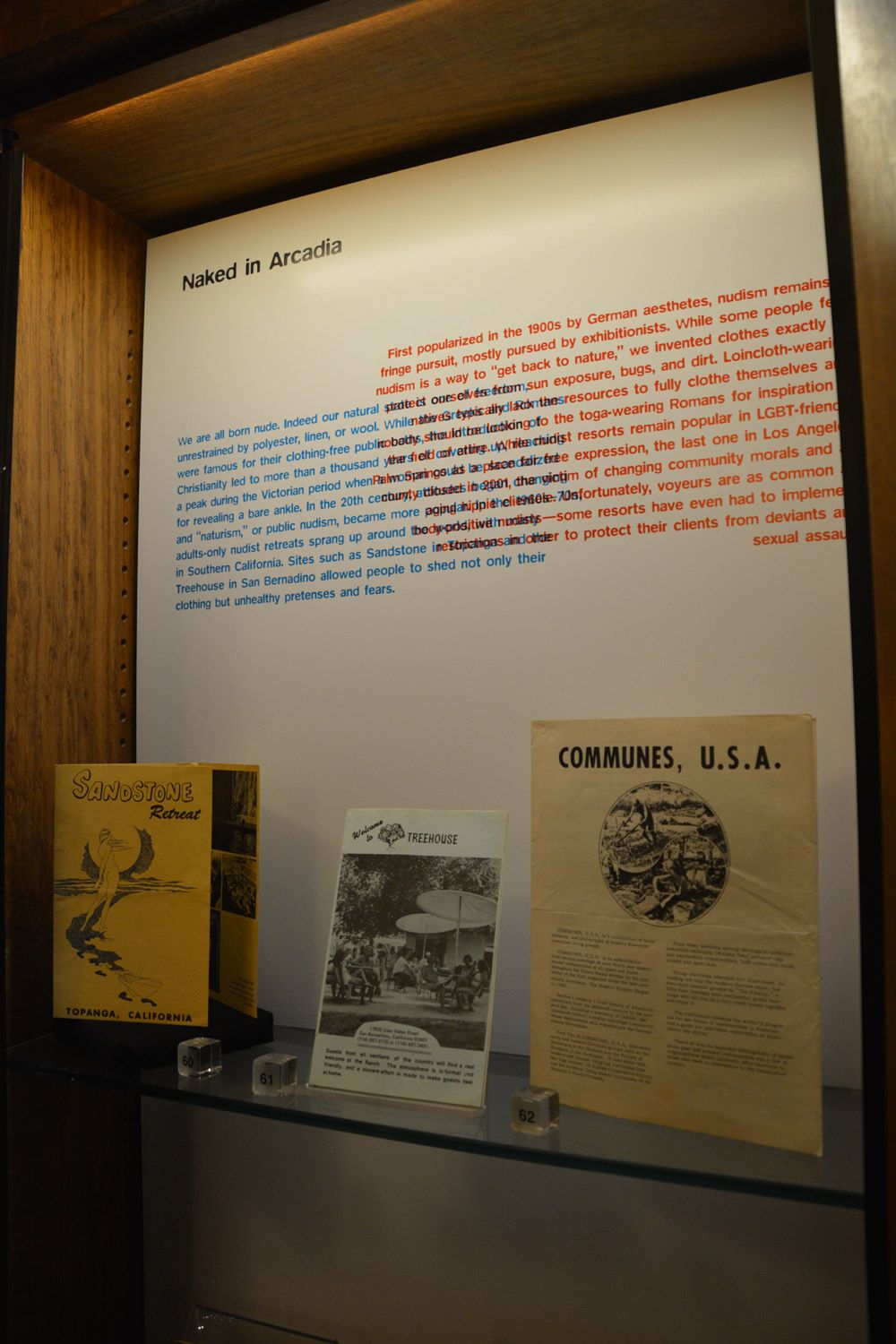

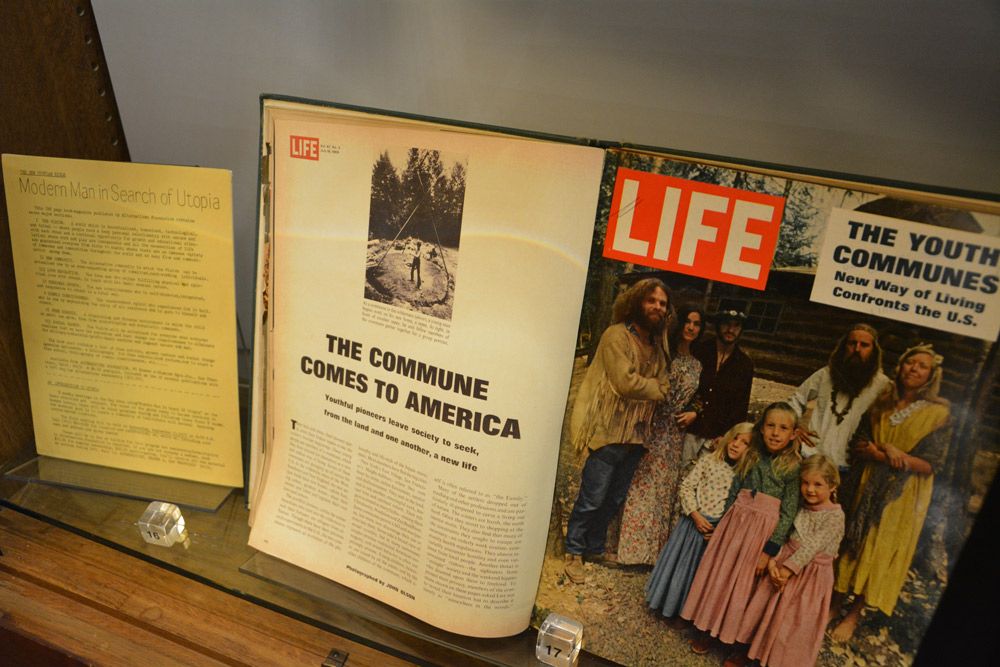

The Doheny Memorial Library exhibit displays archival photos and documents of attempted utopias throughout history placed alongside plaques that look like 3-D images. The plaques text in red and blue layered on top of each other, the plaques' texts appear a little jumbled at first. But by using one of two pairs of glasses offered up at the beginning of the show—one with red lenses and one with blue—visitors can read two stories—and gain a glimpse of both the original ideals and why each utopia failed.

“It often comes down to human foibles,” Gaskill says. “There’s petty bickering, people don’t have fleshed-out ideas, maybe there’s no follow-through. There’s a whole host of reasons why these things fail.”

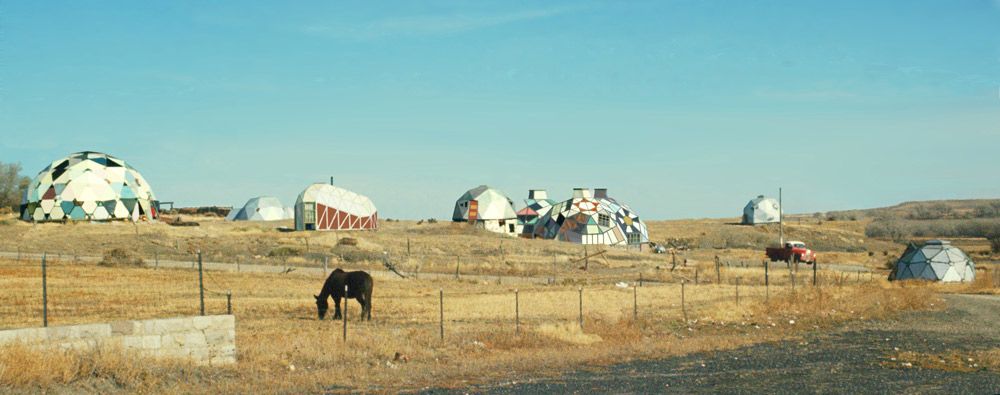

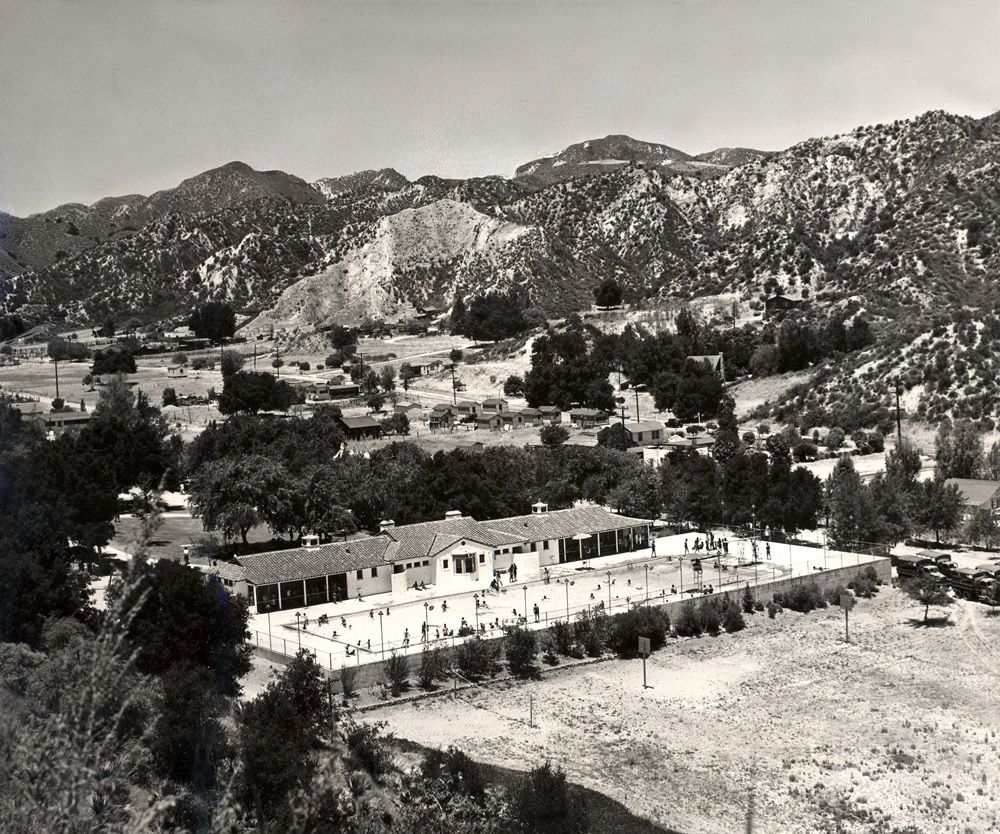

The exhibition has its share of futuristic visions of monorail-based transportation systems and domed cities that look like they were pulled straight out of a science fiction novel. But the show also plenty of attempts at finding ways to carve out communities as escapes from dystopian aspects of reality. There’s documents and photos of attempts to establish LGBT communes in the 1970s, for instance, as well as images of recreation centers built on the far outskirts of Los Angeles specifically for black people in the 1940s.

“Blacks had to go there because they were not allowed to use public parks, they were not allowed to use any recreational facilities in L.A. county whatsoever,” Gaskill says. “They had to travel hours and hours just to get anywhere to be able to just enjoy themselves like [white] people did.”

Obviously, framing havens from segregation and prejudice is a bit different than entirely fictional ones like the one that More originally thought up. But even so, places intended for escape from reality can help demonstrate the ways that mainstream society has been—and can often still be—a dystopia that even the most creative minds might have a hard time imagining up.

500 Years of Utopia is on display at the USC Libraries through February 9, 2017.