Chicago Library Seeks Help Transcribing Magical Manuscripts

Three texts dealing with charms, spirits, and all other manners of magical practice are now accessible online

The Newberry Library in Chicago is home to some 80,000 documents pertaining to religion during the early modern period, a time of sweeping social, political, and cultural change spanning the late Middle Ages to the start of the Industrial Revolution. Among the library’s collection of rare Bibles and Christian devotional texts are a series of manuscripts that would have scandalized the religious establishment. These texts deal with magic—from casting charms to conjuring spirits—and the Newberry is asking for help translating and transcribing them.

As Tatiana Walk-Morris reports for Atlas Obscura, digital scans of three magical manuscripts are accessible through Transcribing Faith, an online portal that functions much like Wikipedia. Anyone with a working knowledge of Latin or English is invited to peruse the documents and contribute translations, transcriptions, and corrections to other users’ work.

“You don't need a Ph.D to transcribe,” Christopher Fletcher, coordinator of the project and a fellow of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, tells Smithsonian.com. “[The initiative] is a great way to allow the general public to engage with these materials in a way that they probably wouldn't have otherwise.”

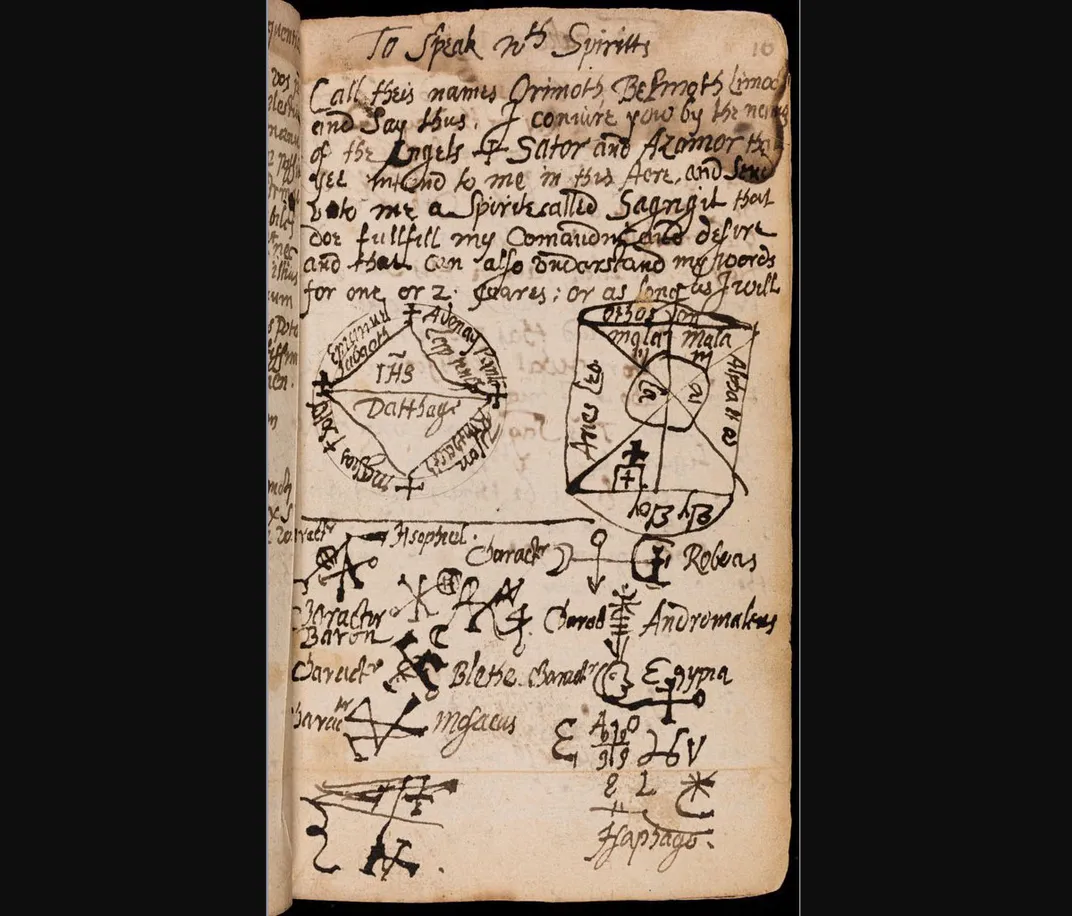

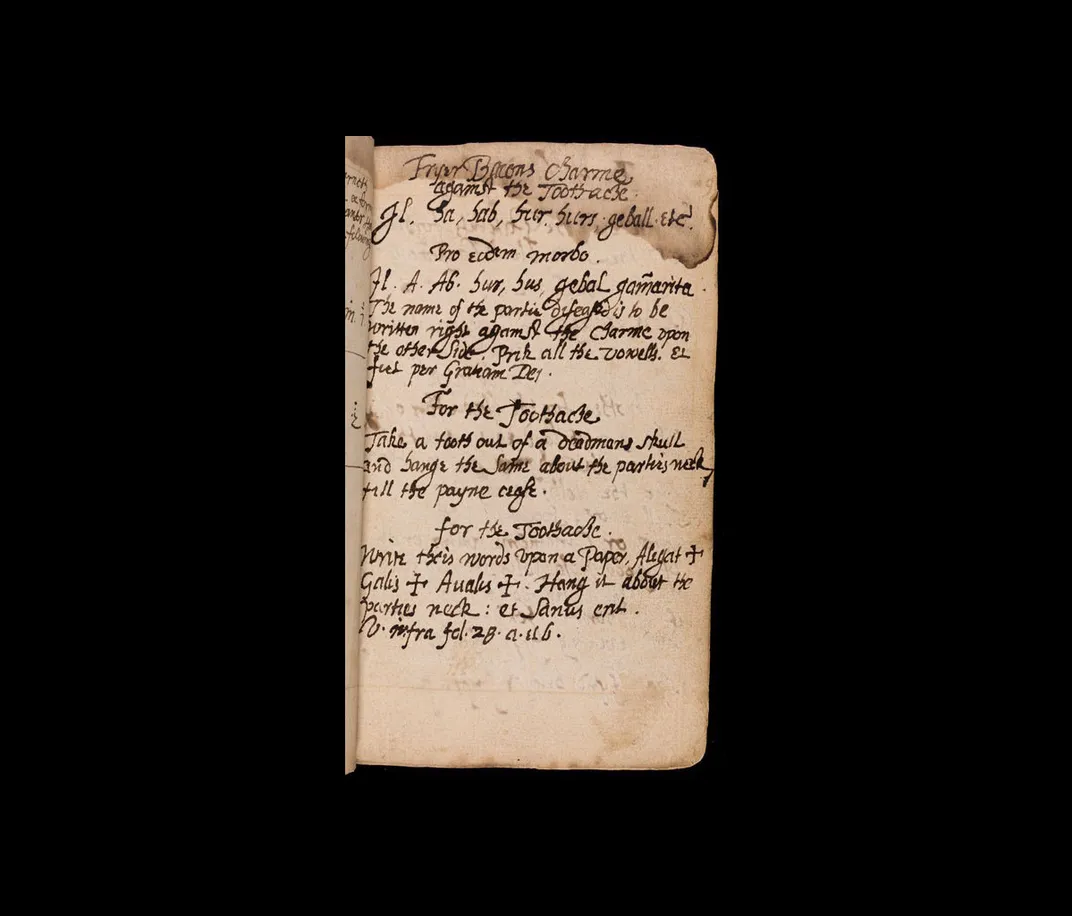

The three manuscripts now available online reflect the varied and complex ways that magic fit into the broader religious landscape of a shifting and modernizing West. The 17th-century Book of Magical Charms contains instructions on a range of magical practices—“from speaking with spirits to cheating at dice,” according to the Transcribing Faith website—but also includes Latin prayers and litanies that align with mainstream religious practices. An untitled document known as the “commonplace book” explores strange and fantastical occurrences, along with religious and moral questions. Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits by Increase Mather, a Puritan minister and president of Harvard who presided over the Salem Witch Trials, expresses a righteous condemnation of witchcraft.

Newberry has brought the manuscripts to light as part of a multidisciplinary project titled Religious Change: 1450-1700, which explores the relationship between print and religion during this period. The project features a digital exploration of Italian broadsides—advertisements for Catholic celebrations and feasts—a blog and a podcast. In September, a gallery exhibition—also titled Religious Change: 1450-1700—will focus on the ways that print galvanized the Reformation, the 16th-century religious movement that led to the foundation of Protestantism. One of the items that will be on display is a copy of Martin Luther’s German translation of the New Testament, which made the Bible accessible to ordinary lay people for the first time.

The magical texts will be on display during the exhibition because, according to Fletcher, they add nuance to our perception of religious life during a period marked by grand, transformative movements. "The Reformation and the Scientific Revolution are very big, capital letter concepts that we all hear about in Western civ courses, or social studies classes,” Fletcher explains. “When we talk about them that way, we lose sight of the fact that these were real events that happened to real people. What we're trying to do with our items is give, as much as we can, a sense of … how individual people experienced them, how they affected their lives, how they had to change in response to them.”

As an example, Fletcher cites The Book of Magical Charms, with its meticulous chronicle of occult practices. “Both protestant and Catholic churches tried very hard to make sure that nobody would make a manuscript like this,” he says. “They didn't like magic. They were very suspicious of it. They tried to do everything they could to stamp it out. Yet we have this manuscript, which is a nice piece of evidence that despite all of that effort to make sure people weren't doing magic, people still continued to do it.”

By soliciting the public’s help in transcribing its magical texts, the Newberry hopes to make the documents more accessible to both casual users and experts. “Manuscripts are these unique witnesses to a particular historical experience, but if they're just there in a manuscript it's really hard for people to use them,” Fletcher says. “[Transcribing the documents] allows other users to come in and do word searches, maybe copy and paste into Google, try to find [other sources] talking about this sort of thing.”

Fletcher quickly scanned the documents before putting them online, but reading through users’ translations has reminded him of some of the manuscripts’ more fascinating and bizarre content. The Book of Magical Charms, for instance, proffers a rather unusual method for alleviating a toothache.

“One of the remedies is finding a dead man's tooth, which apparently was just available in 17th-century England,” Fletcher said. “That was just really cool to see that.”