Don’t Bank on Groundwater to Fight Off Western Drought—It’s Drying Out, Too

Water losses in the west have been dominated by dwindling groundwater supplies

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6f/30/6f3052eb-ca20-4ecc-b74b-cb6a38eaa355/07_29_2014_cap.jpg)

Throughout the Colorado River watershed, water levels are running low. Arizona's Lake Mead, the largest reservoir in the United States, is lower than it's been since it was first filled in the 1930s. As drought continues to sap surface supplies, the conventional wisdom goes, more and more people will have to turn to groundwater to make up the shortfall.

But that's not the whole story. According to new research, western states have been relying on groundwater to replenish surface water sources all along. And now those vital, underground supplies of fresh water are being pushed to the limit.

Last month officials from the Central Arizona Project raised the alarm that Lake Mead is running low. The surface reservoirs at Lake Mead and Lake Powell didn't run into problems sooner, say the researchers in their study, in part because groundwater aquifers have been taking most of the hit.

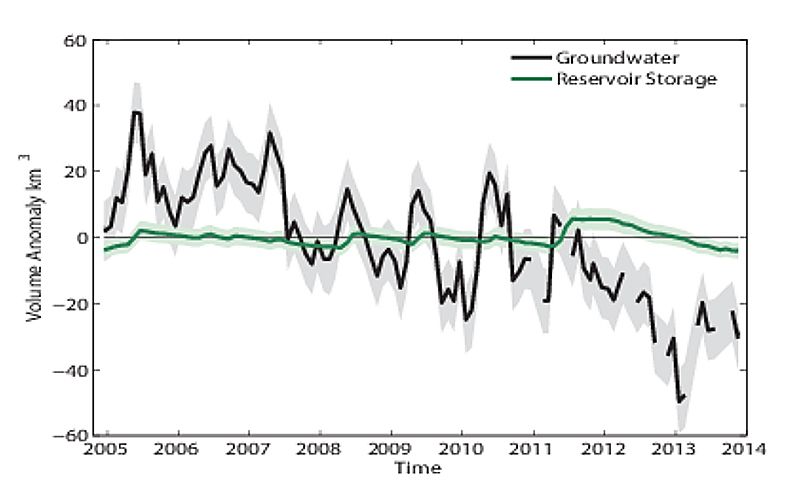

We find that water losses throughout the Basin are dominated by the depletion of groundwater storage. Renewable surface water storage in Lakes Powell and Mead showed no significant trends during the 108-month study period, more recent declines (since 2011) and currently low (<50% of capacity) storage levels notwithstanding. Groundwater storage changes, however, accounted for the bulk of the freshwater losses in the entire Basin (50.1 cubic kilometers; -5.6 ± 0.4 cubic kilometers per year), the majority of which occurred in the Lower Basin.

Taking groundwater into account, the scientists found that in the past nine years the Colorado River basin has lost 15.5 cubic miles of fresh water. That's twice the volume of the Lake Mead, says NASA. Of that fresh water loss, 12 cubic miles was groundwater—a full three quarters of the water lost from the Colorado River basin.

Groundwater is the major source of water for irrigation in the Colorado River basin. A growing reliance on irrigation, a growing population and the ongoing drought have led to an overreliance on groundwater supplies that could cause big problems in the future, the scientists say:

Long-term observations of groundwater depletion in the Lower Basin (e.g. in Arizona, – despite groundwater replenishment activities regulated under the 1980 Groundwater Code – and in Las Vegas) underscore that this strategic reserve is largely unrecoverable by natural means, and that the overall stock of available freshwater in the Basin is in decline.

How close overtaxed groundwater resources are to running dry, though, is difficult to say. The satellite and well measurements used in the study only show the change in groundwater storage, not the total amount left. From NASA:

"We don't know exactly how much groundwater we have left, so we don't know when we're going to run out," said Stephanie Castle, a water resources specialist at the University of California, Irvine, and the study's lead author. "This is a lot of water to lose. We thought that the picture could be pretty bad, but this was shocking."

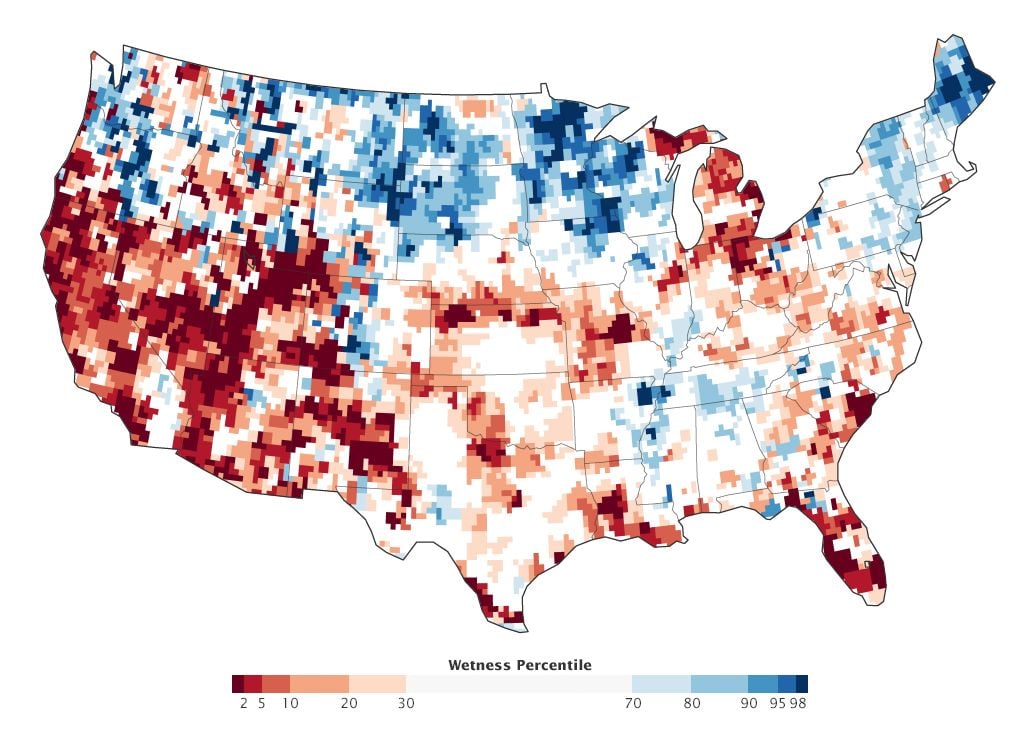

In some places around the U.S., particularly in the West, groundwater stores are likely at their lowest levels in the past 66 years. In this map, based on data from the National Drought Mitigation Center, the colors show the percent chance that the aquifer has been at a level lower than it is right now at any time since 1948.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)