Why Certain Songs Get Stuck in Our Heads

A survey of 3,000 people reveals that the most common earworms share a fast tempo, unusual intervals and simple rhythm

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dc/01/dc01f5cd-20fc-49d3-85aa-afdc595c89cf/9515186675_02a9ad5fed_k.jpg)

Earworms wriggle their way into your brain, lingering there for hours, impossible to excise. The top five out there—determined using a mathematical model—include Queen’s “We Will Rock You,” Pharrell William’s “Happy,” Queen’s “We Are the Champions,” and the Proclaimer’s “I’m Gonna Be (500 Miles).” (Our deepest sympathy for the hours you will now surely spend humming.)

So what turns a song from a passing tune into the mental equivalent of a CD set to repeat? Kelly Jakubowski of Britain's Durham University wanted to figure out just that, reports Joanna Klein for The New York Times. Jakubowski asked 3,000 survey participants what pop tunes most often ended up lodged in their brains. She then compared the melodic features of those songs with popular songs that no one selected as earworms. The research was recently published in the journal Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts.

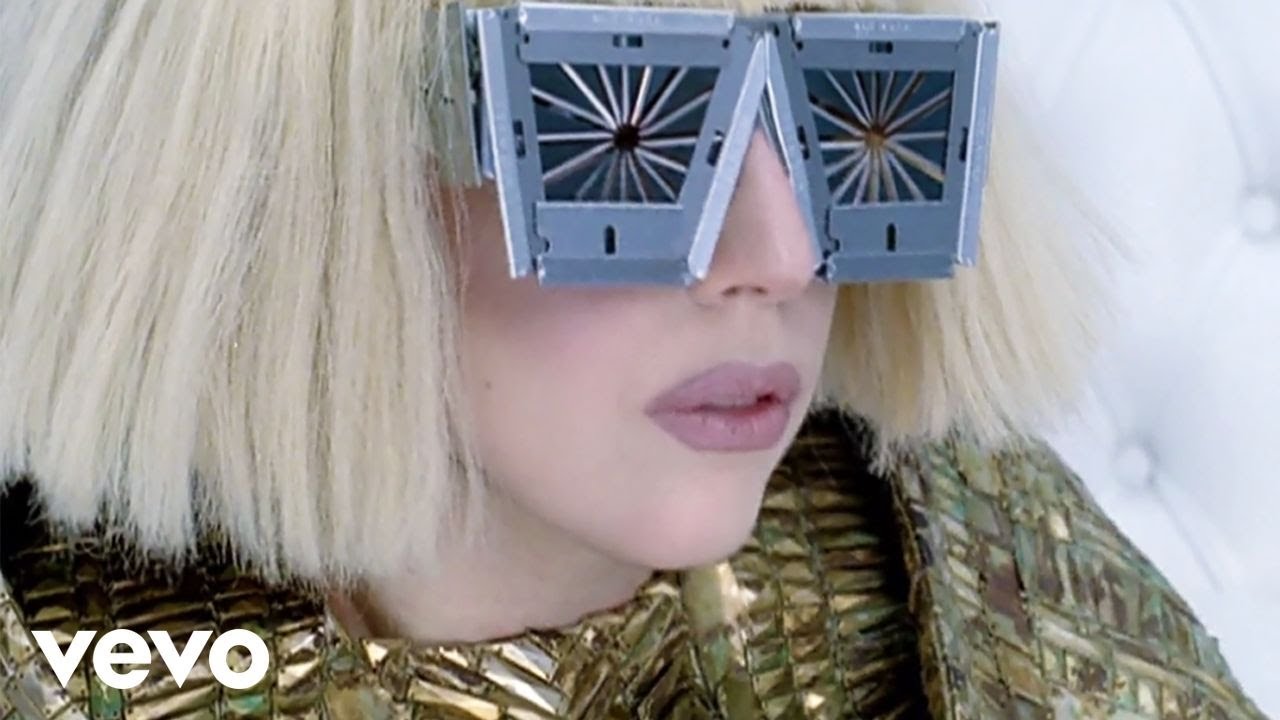

The songs that rise to earworm status have some commonalities, and according to Jakubowski, it’s possible to predict which songs may get stuck on a mental loop. “These musically sticky songs seem to have quite a fast tempo along with a common melodic shape and unusual intervals or repetitions like we can hear in the opening riff of “Smoke On The Water” by Deep Purple or in the chorus of “Bad Romance” by Lady Gaga,” she says in a press release.

In one melodic shape used by many of the strongest earworms, the tone first rises in the first phrase then falls in the second phrase. Jabkubowski says this pattern is seen in “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” as well as other children’s nursery rhymes and Maroon 5’s “Moves Like Jagger.”

Jakubowski says people who listen to more music and sing tend to get more earworms. Ninety percent of her respondents said they got a song stuck in their heads at least once a week, usually at times when the brain is not particularly engaged, like during a shower, walking or cleaning the house.

“We now also know that, regardless of the chart success of a song, there are certain features of the melody that make it more prone to getting stuck in people’s heads like some sort of private musical screensaver,” she says in the release.

Earworms may be more than just an annoyance, Klein reports. They could provide some insight into the cognitive tools humans used to learn and pass along information before the advent of written language. Poems and songs were often used to tell stories or lists of ancestors. Jakubowski tells Klein that learning a song is a complex process that gets into the brain through many pathways, including the eyes, ears and muscles used to play and sing it.

So, are earworms dangerous, or just an annoyance? Klein writes that on one hand, they represent spontaneous cognition, which is associated with creativity and planning—think daydreaming. On the other hand, they can also develop into obsessions or hallucinations.

The inevitable next question, writes Joseph Dussault of The Christian Science Monitor, is: Could these insights help songwriters or jingle writers (By Mennen!) craft catchier, brain-withering tunes? Composer and Brandeis University professor David Rakowski tells Dussault, the answer is probably not.

“Science often takes years and years to find out what artists already know instinctively,” Rakowski tells Dussault. “Knowing the right elements of a great poem doesn’t give you the ability to write a great poem. That doesn’t tell you how to combine and contrast them in artful and fresh ways.” Many Beatles songs, he says, conform to the earworm rules. “[But] I’m not sure if knowing that gives me the ability to write a Beatles song.”

But Jakubowski and her team plan to try, she tells Dussault. In a follow-up study they hope to create a new song based on the principles of earworminess they have identified. They will then tweak the song to identify what aspects of structure make it the stickiest.

This line of research is not without its risks. Jakubowski tells Klein she had Lady Gaga’s “Bad Romance” stuck in her head for two days straight.

Let’s hope you fare better: