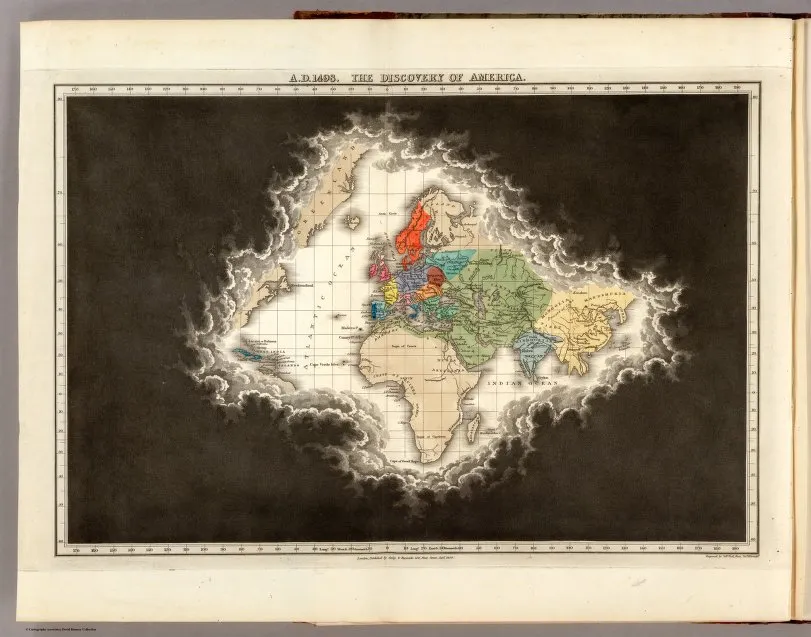

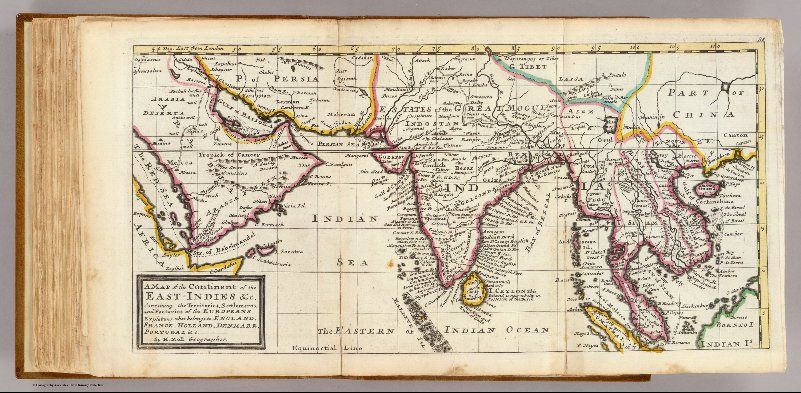

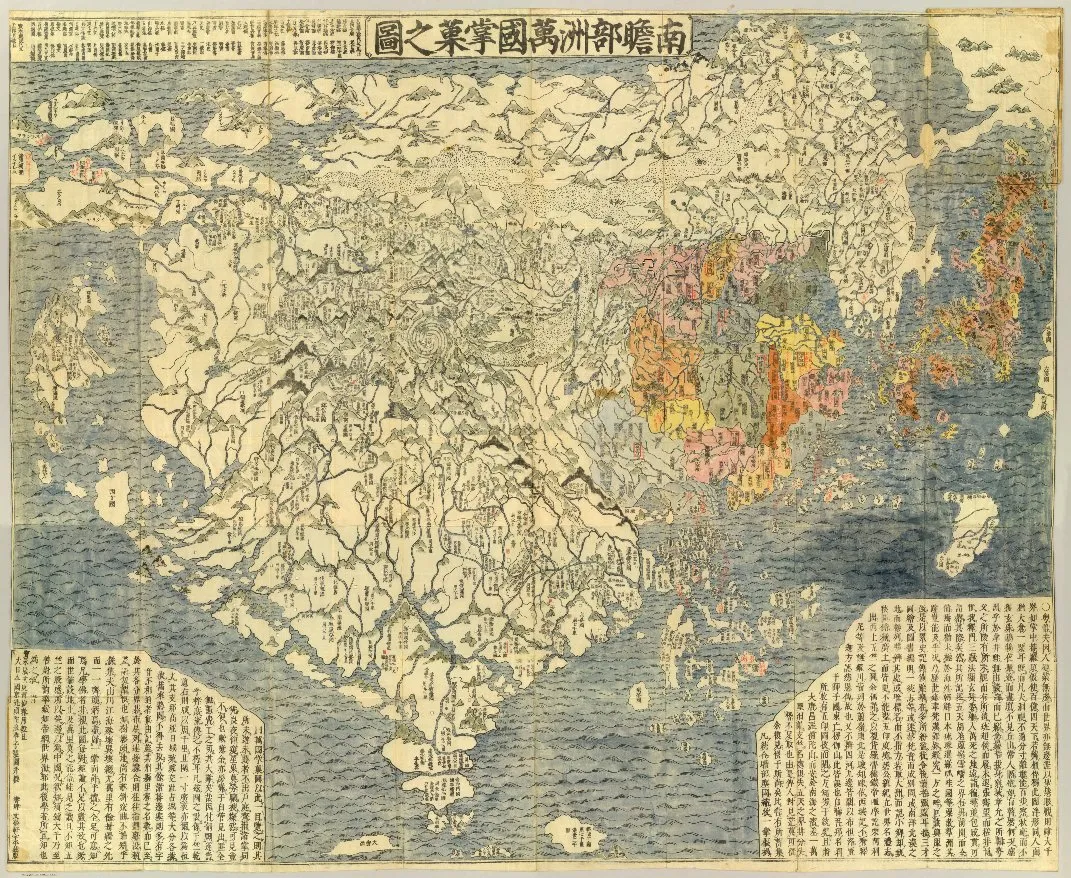

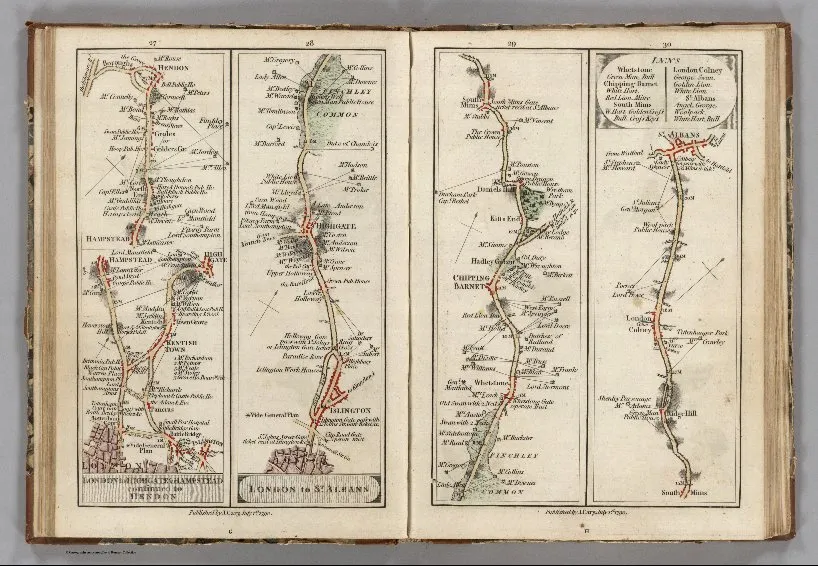

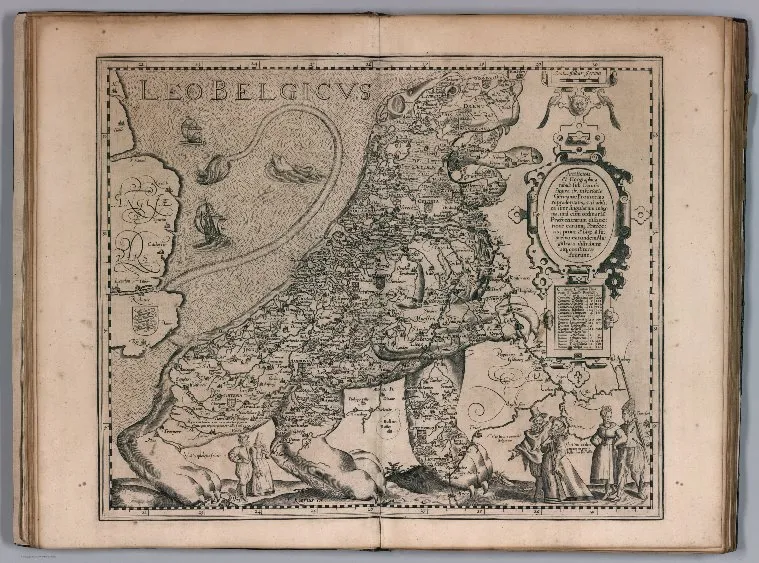

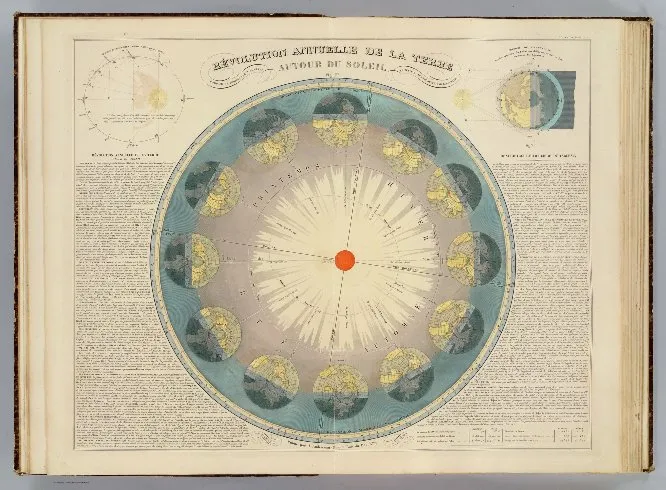

Eight Awesome Maps From Stanford’s New David Rumsey Map Center

A collection of 150,000 historic maps merges paper and digital images in new ways

Cartography geeks rejoice—earlier this week Stanford University’s Green Library unveiled the David Rumsey Map Center, a collection of more than 150,000 maps, atlases, globes and other historical treasures donated by the retired San Francisco real estate developer.

“It’s one of the biggest private map collections around,” Matt Knutzen, the geospatial librarian at the New York Public Library tells Greg Miller at National Geographic about Rumsey's collection. “But what’s more impressive from my perspective is that he’s developed it almost as a public resource.”

That’s been Rumsey’s goal since he began collecting maps in the mid 1980s. He spent two decades as a real estate investor for The Atlantic Philanthropies and made enough to amass his huge collection and retire at the age of 50. By 1999, he realized his map collection had not only grown quite large, but was also full of rare images that others might be interested in. He decided to start digitizing his collection and putting the images online. At at time when dial-up was still common, however, it was difficult for users to access his maps. To get around that obstacle, Rumsey developed a new company, Luna Imaging. The company's software, which offered a new way to display large images, is still used by libraries and museums around the world today.

“I’m not a possessive collector,” he tells Miller. “What I’m most excited about is acquiring something other people can learn from and use.”

Rumsey continued to digitize his maps to DavidRumsey.com, which currently hosts 67,000 images. At the age 71, however, he decided to hand over his physical collection and digital images to Stanford.

“Stanford is a pioneer in the digital library world. When I was thinking of where to donate my collection, I wanted to ensure the preservation not only of the original materials but also the digital copies I made,” Rumsey says in a press release. “I knew Stanford would be the best place for both.”

While physical copies of the donated maps and globes are displayed throughout the center, its biggest attraction, as Nick Stockton writes for Wired, has to be the giant touch screen displays that are set up, which allow researchers to zoom in on minute details on digitized maps.

The digital maps also have georeferencing capabilities. Since mapmakers over time have used different scales and may have exaggerated the size of a lake or misplaced a mountain, georeferencing technology tags certain points on digital maps so researchers can accurately compare or even overlay maps from different decades or centuries. This means that the maps can be used to measure land use, movements in river systems, settlement patterns and other changes through the centuries.

Other universities and institutions in the U.S. house world-class map collections, but as G. Salim Muhammed, director and curator of the David Rumsey Map Center points out, Stanford's is the first fully integrated map center with technology for modern research applications, as Stockton reports.

The Map Center will be used for classes and research projects in the morning and open to the public in the afternoons. The Stanford Digital Repository, on the ground floor of the library, will continue to scan the maps and take photos of them using a 60-megapixel camera, giving each one a permanent online address. “This link always takes you to that map, from now until forever,” as Rumsey explains to Stockton.

It remains to be seen how researchers and students will use the high-tech map collection, but Rumsey is optimistic. “The future defines what this place is,” he tells Miller.