Fannie Farmer Was the Original Rachael Ray

Farmer was the first prominent figure to advocate scientific cookery. Her cookbook remains in print to this day

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/72/ed/72eda67e-d6d9-49a2-aa8e-27159995b182/cookbook.jpg)

You probably know how a recipe looks: ingredients at the top, step-by-step instructions below. What you may not know is that this recipe format owes a lot to one American celebrity cook.

Fannie Merritt Farmer, born in 1857, changed American cooking forever. By the time she opened her own cooking school on this day in 1902, she had already made what would be her most lasting contribution–a cookbook that is still in print today–but as Miss Farmer’s School of Cookery showed, she was far from finished.

Farmer started attending the Boston Cooking School in the late 1880s, where she learned the precepts that formed the basis of her approach to kitchen matters.

“The Boston Cooking School believed in a scientific approach to cooking and housekeeping,” writes KeriLynn Engel on her blog Amazing Women in History. “They taught not only how to cook, but also about nutrition, sanitation, chemical analysis and household management.” Farmer, who was much older than many of her fellow students, did extremely well. After graduation, she stayed on at the school as first an assistant to the director, and then the school’s principal.

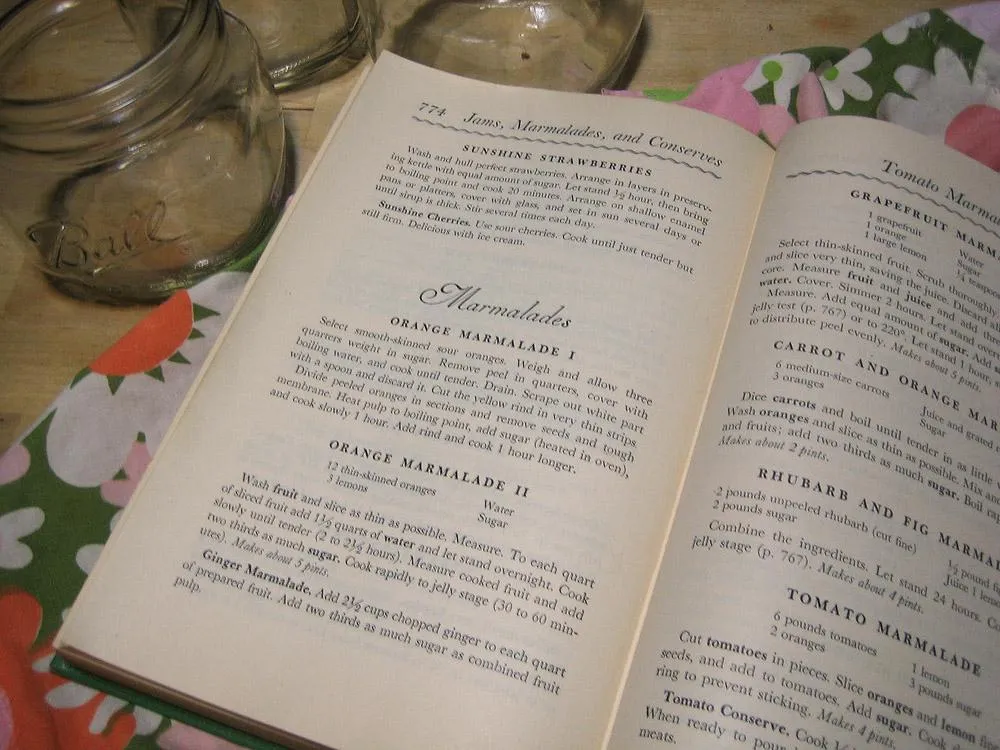

It was during her time at the school that she first published The Boston Cooking-School Cookbook, which is better known today as The Fannie Farmer Cookbook. Little, Brown and Company, the publishers of the cookbook, were afraid of losing money on the book, according to Minnesota State University’s Feeding America blog–so they had the author fund the 3,000-volume first run herself. But she got the last laugh: “It has been in print from its first appearance in 1896 until the present day,” according to Feeding America, “although the newer editions are updated and revised so that Fannie might not easily recognize them.”

Proceeds from The Boston Cooking-School Cookbook helped Farmer open her own school. By this time, she was sort of a celebrity cook–like TV cook Rachael Ray, she offered ordinary people recipes they were able to prepare. In the days before television or radio, a wildly popular cookbook was a good outreach tool for Farmer’s methods. (To be fair, Ray says things like “Eyeball it!,” so Farmer, with her exacting approach to measurement, wasn't exactly the same.)

The income also provided the basis on which she toured, lectured on cooking and educated medical professionals about food for the sick, writes History.com. “Farmer’s expertise in the areas of nutrition and illness led her to lecture at Harvard Medical School,” writes the website. "Her largely intuitive knowledge of diet planning predated the modern field of nutrition," writes Encyclopedia Britannica. But for all that, her focus on food as an essential part of health seems very modern.

The reason for the book’s lasting popularity is related to Farmer’s career as a teacher, writes Feeding America. She “wrote as if she were teaching,” with no narrative flourishes. This scientific approach to food preparation is exemplified by the fact that her cookbook, unlike others of the period, put clear measurements (for example, a cup of flour or a tablespoon of sugar) at the heart of a recipe. Farmer was a pioneer of the “structure and form of what we think of today as a recipe,” according to University of Washington professor Joe Janes, who studies information history.

But another reason might be that, by teaching easily replicable cooking skills and recipes, Farmer was giving ordinary people control over their food and by extension their physical health. In her cookbook, Farmer called "the principals of diet... an essential part of one's education. Mankind will eat to live," she wrote, "[and] will be able to do better mental and physical work, and disease will be less frequent."

In Farmer’s own lifetime, more than 360,000 copies of the book, in English, French, Spanish, Japanese and Braille were printed. After her death, family members took on the work of revising the cookbook and adding further recipes. The book continues to be revised, although it’s no longer run by her family. Farmer's cooking school lasted into the 1940s, though she herself died in 1915.