How Booker T. Washington Became the First African-American on a U.S. Postage Stamp

At the time, postage stamps usually depicted white men

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/80/bd/80bd281c-7607-4d05-9b4d-5cbc9010d6ad/1d_btw_stamp-1.jpg)

What’s in a stamp? Sure, the tiny adhesive objects help mail go to and fro, but what’s on stamps themselves says a lot about a country’s priorities. Seventy-six years ago today, philatelic history was made when the first black person appeared on a stamp in the United States.

The person in question was Booker T. Washington, the legendary educator and author who went from slave to esteemed orator and founder of the Tuskegee Institute. Washington’s inclusion on not one, but two postage stamps during 1940 represented a postal first—one that was hard-fought and hard-won.

To understand just how important it was to see a person of color on a U.S. postage stamp, you need only imagine what stamps looked like during the first half of the 20th century. Daniel Piazza, chief curator of philately at the Smithsonian National Postal Museum, tells Smithsonian.com that at the time, the only subjects thought worthy of being depicted on stamps were “presidents and generals and such,” white men whose national stature was deemed significant enough to rate inclusion on the nation’s envelopes.

By 1940, women had only appeared on stamps eight times—three of which were depictions of Martha Washington, and two of which were fictitious women. In the 1930s, controversy broke out over whether the Post Office Department should issue a stamp that portrayed Susan B. Anthony and celebrated women’s suffrage as opposed to stamps that portrayed military figures. Anthony’s supporters prevailed, and the struggle in turn inspired a black newspaper to ask why there were no African-American people on U.S. postage. “There should be some stamps bearing black faces,” wrote the paper.

Whose face should those stamps represent? Booker T. Washington immediately emerged as a candidate. As a former slave and influential member of the African-American community, Washington was nominated by supporters and eventually Franklin Delano Roosevelt agreed.

But when plans to include Washington in a series of ten-cent stamps depicting influential educators were announced, they were slammed by critics. “There was a lot of explicitly racist criticism of the stamp,” Piazza explains, but the stamp’s denomination was even more incendiary.

“At the time, there was not a lot of need for a ten-cent stamp,” says Piazza. “A three-cent stamp would have gotten heavy usage, but a ten-cent stamp would not. Supporters of the stamp alleged that he had been put on the stamp to minimize the extent to which the stamp would be purchased or used.” At the time, first-class postage only cost three cents, putting the ten-cent stamp more on the level of one that would be used to send particularly bulky or expensive mail. Critics also pointed out that the stamp only showed Washington not as a public figure, but in a much more “safe” context as an educator.

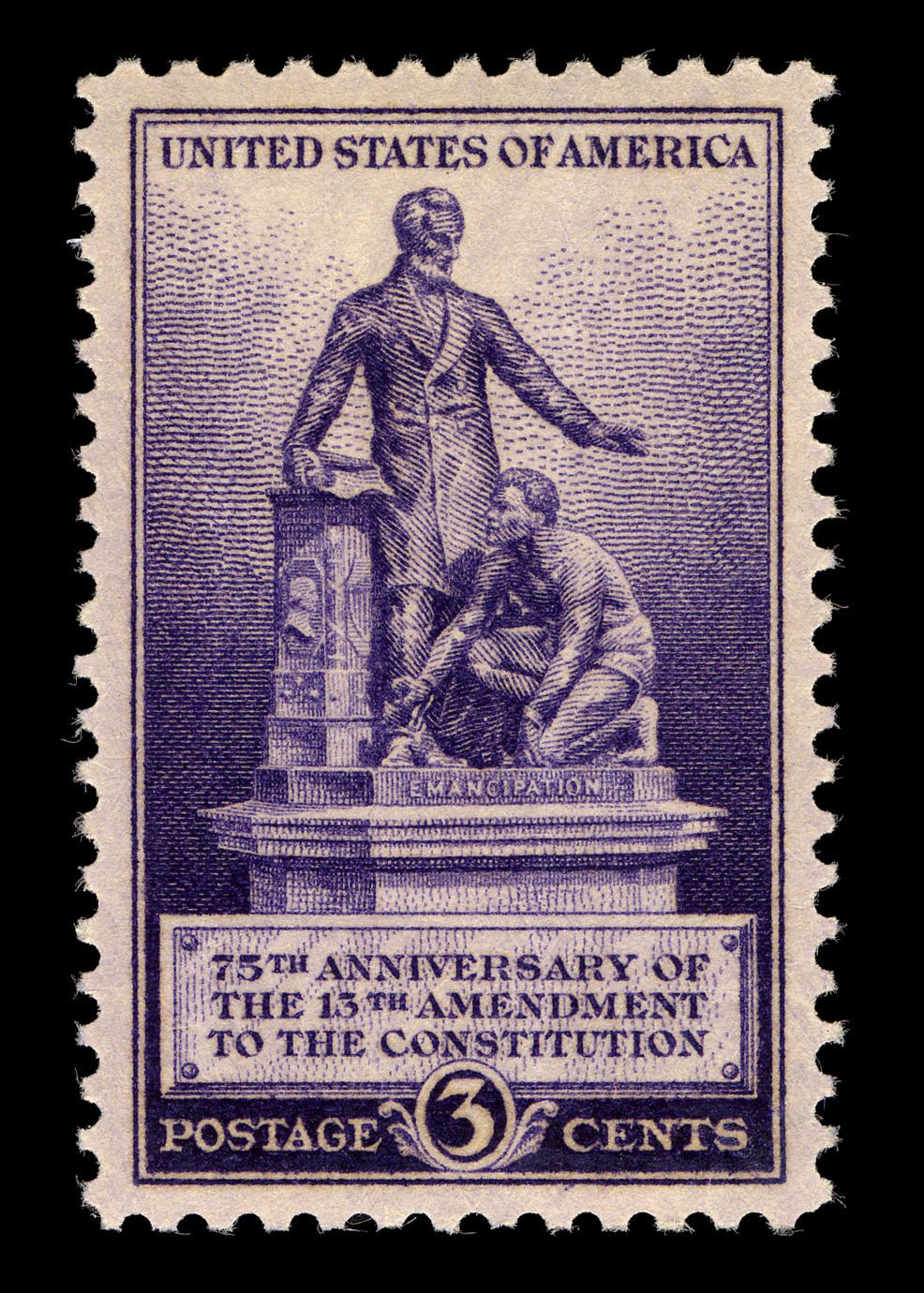

Perhaps in response to that controversy, another stamp featuring an African-American was released that year. By modern-day standards, though, the three-cent stamp was even more problematic: It celebrated the passage of the 13th Amendment with an image of a black man kneeling beneath a figure of Abraham Lincoln. Was a more widely available image of a still-subservient man of color preferable to an expensive stamp that stuck a prominent black man in a lineup of educators?

Today, it is common to see black Americans—and people of many different races and ethnicities—on postage stamps. Piazza says that the struggle to include people of different backgrounds on U.S. postage stamps reflects changing concepts of race and inclusion. “People started to get the idea that being left off stamps needed to be corrected,” he says. “At the time, it was totally unheard-of. It’s persisted even into an era in which a lot of people might consider stamps to be kind of obsolete.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)