How Experts Are Digitizing Ancient Manuscripts

Digital preservation is more work than it might seem

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8b/22/8b22dfc6-ac29-4798-841a-79856666a4c8/british_library1.png)

In recent years, conservators and preservationists have turned to digital tools to preserve old texts and manuscripts. There are a lot of advantages to these techniques—not only can they be stored and cleaned up even if the originals are too delicate, but digitizing old books can allow more people to read them than if they only existed as physical objects. However, when it comes to restoring these books, it takes a lot more than simply scanning the pages into a computer.

Conserving books is as much an art form as it is a skilled trade. Researchers study how to make books themselves in order to understand how older manuscripts and documents were put together, as well as what materials were used to originally make them. Meanwhile, binding techniques evolved throughout the centuries, with different eras and areas using different styles to keep their books whole, Larry Humes reports for the Sarasota Herald-Tribune.

“In much the same way, you can’t restore a 16th-century book in the way you would a 20th-century book,” conservator Sonja Jordan-Mowery tells Humes. “They weren’t made the same way. Not only is it not the same materials, but the techniques that were used are not the same. A properly trained conservator will not only know how to do it, but will know what is historically sympathetic to the material.”

Being sensitive to the materials and techniques used to make an ancient book can reveal all sorts of information about the documents it contains. But like any other kind of repair job, there are bad restorations, too. The worst ones can destroy priceless artifacts, while some simply obscure precious information due to carelessness or a lack of skill, as conservator Flavio Marzo writes for the British Library’s Collection Care blog.

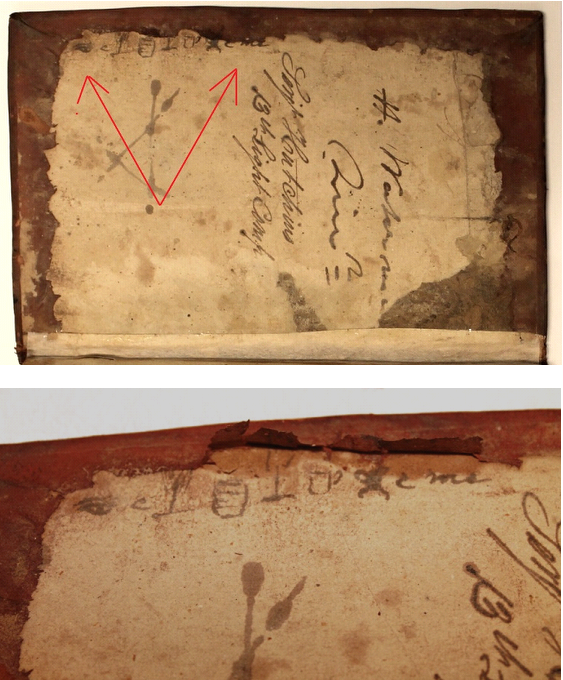

In one recent instance, Marzo was given a manuscript from the British Library’s Delhi Collection to scan as part of a digitization project. However, a previous restoration attempt had left the binding damaged in such a way that made it impossible to see or scan some of the text. When Marzo undid the stitching to repair the book, he uncovered a series of annotations hidden inside the edges of the pages, as well as a mysterious set of scribbles on the inside of the manuscript’s cover. When he and his colleagues decoded them, they discovered that the previously hidden scribbles were a coded puzzle that translated to “I see you but you cannot see me."

As Marzo writes, conservation experts work to make sure the integrity of the documents remain intact while ensuring they preserve details like that, those "unique and invaluable physical features related to [a document's] history and use.”