Forget the Hazy Clouds—The Internet is in the Ocean

This new video explores the 550,000 miles of cable that keeps the internet humming

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/03/6b030a09-9721-4994-b101-57bfb2ca850c/42-29964870.jpg)

With the recent wave of concern over Russian subs and spy ships encroaching on undersea data cables, Americans have become all too aware that the seemingly intengible data stored up in the "cloud" isn't nebulous at all. Rather, the mechanics of the internet are solid, taking form in cables that snake across the ocean floor.

Though this may seem like a Cold War scare, the fears are new, report David E. Sanger and Eric Schmitt for The New York Times. Cutting the cables in the right places would sever the data lifeline of the West. The cables are so vunerable that last year shark bites even prompted Google to reinforce their network.

Amidst these tensions nags a different question: How does the internet actually work?

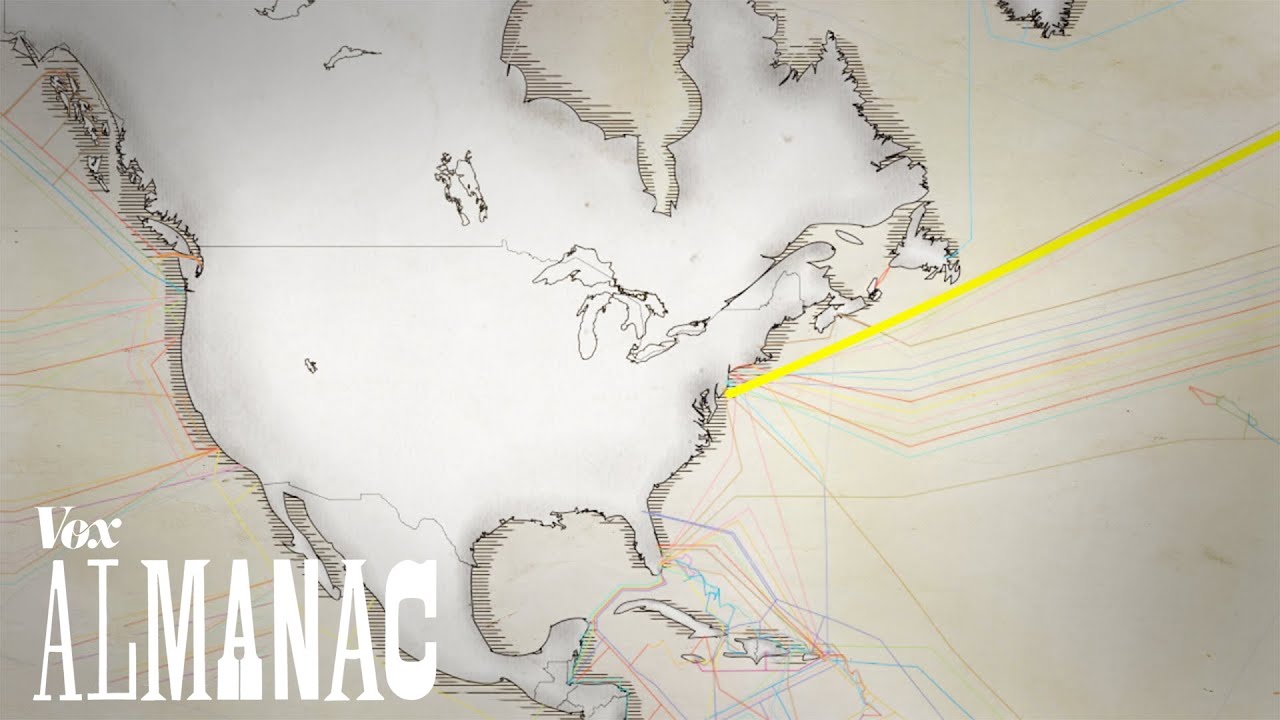

In a new video, Phil Edwards and Gina Barton of Vox explore the network of thin, fiberoptic cables that distribute 99 percent of international data. "If you held one in your hand, it’d be no bigger than a soda can," Edwards says in the video.

Submarine cables aren’t exactly new, but they are a big deal in the modern world. While satellites are needed to beam the Internet to some places, like remote research bases in Antarctica, cables on the seafloor are more reliable, redundant (good for backup in the case of damage) and fast.

Tech companies and various countries are even investing in their own routes and connections. The telecommunications marketing researcher and consulting group TeleGeography reports that in 2015, 299 cable systems are "active, under construction or expected to be fully-funded by the end of 2015."

In honor of all those cables, TeleGeography created a vintage-inspired map, which is well worth a gander. The map includes the latency, or the milliseconds of delay a ping takes to travel, from the U.S., U.K., Hong Kong and several other countries.

So how did the more than 550,000 miles of cables get down there? Edwards explains at Vox:

The process for laying submarine cables hasn't changed much in 150 years—a ship traverses the ocean, slowly unspooling cable that sinks to the ocean floor. The SS Great Eastern laid the first continually successful trans-Atlantic cable in 1866, which was used to transmit telegraphs. Later cables (starting in 1956) carried telephone signals.

The internet is also wired through cables that crisscross countries and someday in the future it might exist in hundreds of tiny satellites. But for now, it’s on the ocean floor.