Genetic Sleuthing Clears ‘Patient Zero’ of Blame for U.S. AIDS Epidemic

Scientists debunk the myth of the man once thought to have brought the virus to the states

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2b/9d/2b9ddde0-47cf-4ece-ac34-be1040023033/hiv-budding-color.jpg)

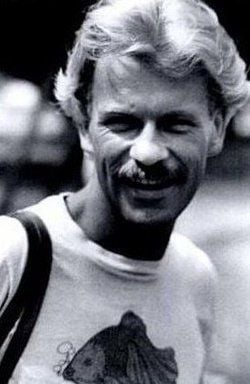

For decades, the world thought that a Canadian man named Gaétan Dugas was the person who brought HIV to the United States, setting a deadly epidemic in motion by spreading the virus to hundreds of other men. For decades, the legend has loomed large in the early history of a disease that ravaged the gay community and has gone on to become a persistent public health threat. But now, more than 30 years after his death, it turns out that Dugas was not to blame. As Deborah Netburn reports for The Los Angeles Times, a new investigation of genetic and historical evidence has not only exonerated Dugas, but has revealed more about how AIDS spread around the world in the 1980s.

In a new paper published in the journal Nature, a group of biologists, public health experts and historians describe how they used genetic testing to demonstrate that Dugas was not the first patient in the U.S. with AIDS. Instead, they found that in 1971 the virus jumped to New York from the Caribbean, where it was introduced from Zaire. By 1973, it hit San Francisco, which was years before Dugas is thought to have been sexually active.

Dugas, who was a flight attendant, later claimed to have had hundreds of sex partners, whom he met in underground gay bars and clubs in New York. Though his name was never released to the public by medical practitioners, Netburn writes, it became public in Randy Shilts' book And the Band Played On, a history of the first five years of the AIDS epidemic. Shilts portrayed Dugas as an amoral, sex-obsessed “Typhoid Mary.” And despite calls from medical historians to the public to expose the inaccuracies of the depiction, Dugas' name became inextricably associated with spreading the disease that took his life in 1984. That was, in part, due to his reported refusal to acknowledge that the disease could be spread via sexual contact—a refusal that Shilts used to paint Dugas as someone who infected people with HIV on purpose.

But regardless of how Dugas perceived AIDS, it now appears he could not have been the person who brought it to the U.S. Researchers got their hands on a blood serum sample from Dugas taken the year before his death and used it to assemble an HIV genome. They also studied serum samples of gay men who had blood taken in the late 1970s for a study on Hepatitis B. The samples showed that 6.6 percent of the New York men studied and 3.7 percent of the San Francisco men had developed antibodies to HIV.

Then the team sequenced 53 of the samples and reconstructed the HIV genome in eight. The samples showed a level of genetic diversity in the HIV genome, which suggests that Dugas was far from the first person to develop AIDS.

It turns out that a tragic misreading fueled Dugas’ reputation as “Patient Zero.” Despite being initially identified as the CDC’s 57th case of the then-mysterious disease, writes Netburn, at some point he was tagged with the letter “O” in a CDC AIDS study that identified him as a patient “outside of California.” That O was read as a number at some point, and Shilts, feeling the idea of a patient zero was “catchy,” identified Dugas in his book.

Before Dugas died, the mechanisms by which HIV were spread were still unknown and the disease was still thought to be some form of “gay cancer.” Dugas was just one of thousands of men forced to take their sex lives underground in an era of intense stigma against homosexuality. Many such men found a community in gay clubs and bathhouses where they could socialize with other gay men—the same locations where HIV began to spread with growing rapidity in the 1970s.

New York and San Francisco were the only places where gay men could express their sexuality with any sense of openness. As Elizabeth Landau reports for CNN, a doctor named Alvin Friedman-Kien, an early researcher of the not-yet-named disease, met with a group of gay men in New York in 1981 to talk to them about health problems plaguing the gay community. He was met with resistance from men who refused to put their sexuality back in the closet. “They weren’t about to give up…their open new lifestyle,” he recalled.

As a man who infected other men with HIV, Dugas was certainly not unique—and he helped scientists make sense of the outbreak by identifying his sex partners and cooperating with public health officials during his illness. But he also paid a price for that openness, as medical historian Richard A. McKay writes. As paranoia about the mysterious virus grew within the gay community, Dugas, whose skin was marked with the cancer that was often the only visible indicator of AIDS, was discriminated against, shunned and harassed. And after his death, when he was identified as Patient Zero, his friends complained that Shilts had portrayed a one-dimensional villain instead of the strong, affectionate man they knew.

Today, the idea of a “Patient Zero” or index case is still used to model how epidemics spread. But given that an index case is only the first person known to have a condition in a certain population rather than the first person affected by it, the idea itself is limiting. In the case of AIDS, which wiped out an entire generation of gay men in America and has killed more than 35 million people since the 1980s, it is now clear that a Patient Zero may never be identified. But thanks to Dugas, now scientists know even more about the origins and early spread of the disease.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)