The Man Who Invented Nitroglycerin Was Horrified By Dynamite

Alfred Nobel–yes, that Nobel–commercialized it, but inventor Asciano Sobrero thought nitroglycerin was too destructive to be useful

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/76/74763e07-5b3f-4c0f-9fd9-0fe99f651eb9/dynamite.jpg)

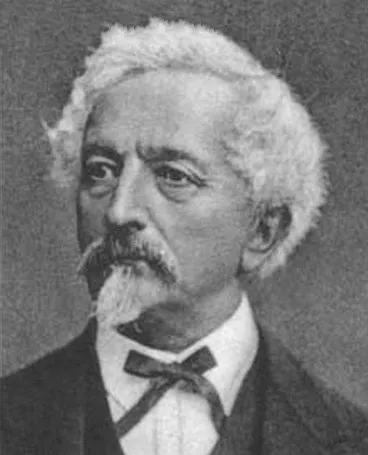

Ascanio Sobrero, born on this day in 1812, invented nitroglycerin. He just didn’t see any use for it—even though it became, in the hands of Alfred Nobel—yes, that Nobel—the active ingredient in dynamite.

Sobrero, like Nobel, was a chemist who studied with professor J.T. Pelouze in Paris, according to the Nobel Prize website. It was during his time with Peleuze, in the mid-1840s, that he came up with a substance he initially called “pyroglycerine,” made by adding glycerol to a mix of nitric and sulfuric acids. The oil this produced was incredibly explosive, writes Nobel biographer Kenne Fant, and Sobrero considered it too destructive and volatile to have any practical uses. A few years later, though, Nobel thought nitroglycerin’s explosive tendencies could be tamed.

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, Nobel studied at Pelouze’s lab during a brief stint in Paris while he was studying chemistry. He had a long interest in the use of explosives, the encyclopedia writes, influenced by the family business selling explosive mines and other equipment. In the early 1860s, having completed his education, he began experimenting with explosives.

“At the time, the only dependable explosive for use in mines was black powder, a form of gunpowder,” the encyclopedia writes. "Nitroglycerin was a much more powerful explosive, but it was so unstable that it could not be handled with any degree of safety.” Nobel built a small nitroglycerin factory to supply his experiments and set to work.

The solution he devised was a small wooden detonator with a black powder charge that was placed in a metal container full of nitroglycerin. When it was lit and exploded, the liquid nitroglycerin would also explode. A few years later, in 1865, he invented the blasting cap, which replaced the wooden detonator.

“The invention of the blasting cap inaugurated the modern use of high explosives,” the encyclopedia writes. This early period of experimentation cost Nobel his factory, which blew up, and the deaths of a number of workmen as well as his brother, Emil.

In 1867, Nobel’s discovery that nitroglycerin mixed with an absorbent substance was much safer to handle led to the invention of dynamite.

The story of how much credit this budding industrialist gave to the inventor of nitroglycerin is a bit muddied by later conflict between the two men, but the Nobel Prize website and Nobel's biographer Fant both state that Nobel never tried to claim credit for that discovery.

However, Sobrero, who had been badly injured in a nitroglycerin explosion during his work, was at first “mortified” to hear about Nobel’s work, according to the Nobel Prize website. "When I think of all the victims killed during nitroglycerin explosions, and the terrible havoc that has been wreaked, which in all probability will continue to occur in the future, I am almost ashamed to admit to be its discoverer,” he said of nitroglycerin after dynamite had become a relatively common substance. But after dynamite made the Nobel family extraordinarily rich, some accounts say that he was resentful of their riches and didn’t feel he was given enough credit for his work, writes Fant.

He stated that the only salve to his conscience was the fact that nitroglycerin would have “been discovered sooner or later by some chemist,” but another of the substance’s properties should also have given him cause for hope.

As far back as the 1860s, writes Rebecca Rawls for the Chemical and Engineering News, the positive effects of nitroglycerin on people with heart conditions was being explored. It helped ignite a field of research into heart medicine, write Neville and Alexander Marsh in Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology, and it remains important in heart care more than 150 years later.