Mass Bleaching Destroys Swaths of the Great Barrier Reef

Surveys show that 55 percent of reefs surveyed were severely affected by high water temperatures, with half of those expected to die

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7b/65/7b652045-b623-415c-8380-3fecb6bc18bd/bleached_coral.jpg)

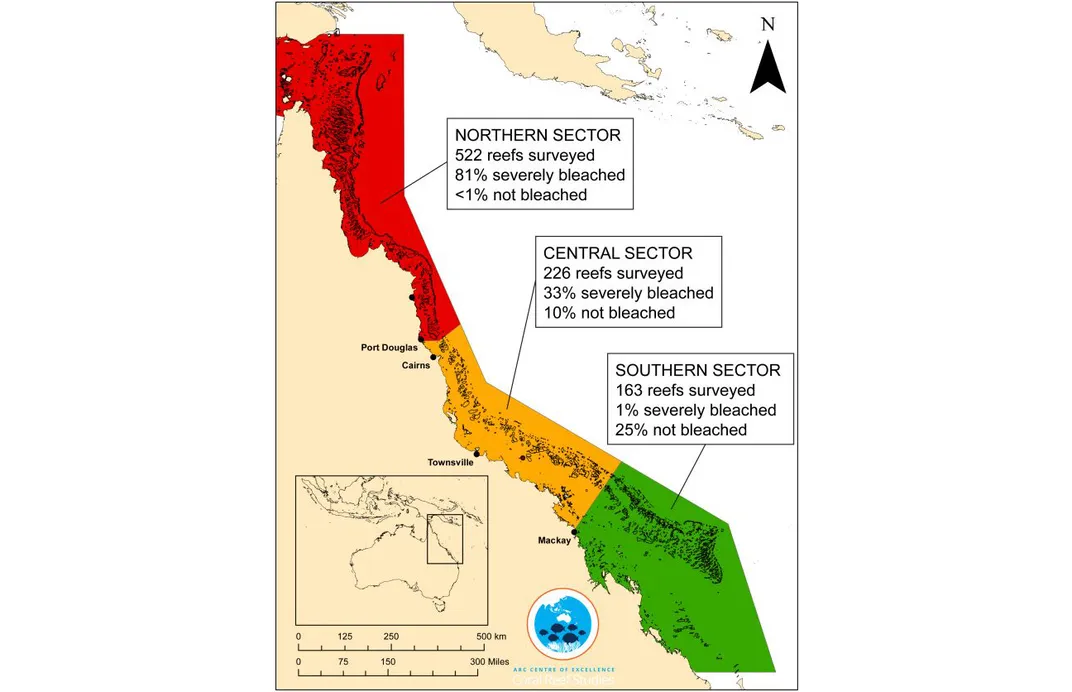

A massive survey of the Great Barrier Reef in Australia reveals that 93 percent of the smaller reefs that make up the complex have been hit by a mass bleaching event, the largest ever recorded along the 1,400-mile-long World Heritage Area. More than half of the 911 reefs investigated so far are experiencing severe bleaching, writes to Michael Slezak at The Guardian. Only 68 reefs escaped bleaching at all.

Terry Hughes, head of Australia’s National Coral Bleaching task force tells Slezak that in the last two mass bleaching events in 1998 and 2002 about 40 percent of reefs were unaffected and only 18 percent were severely bleached. “By that metric, this event is five times stronger,” Hughes says, pointing out that thus far 55 percent of reefs surveyed have severe bleaching.

“We’ve never seen anything like this scale of bleaching before. In the northern Great Barrier Reef, it’s like ten cyclones have come ashore all at once,” Hughes says in a press release.

Coral polyps depend on a symbiotic relationship with a type of algae called zooxanthellae, which give coral their vibrant colors. Under stress, the coral expels the zooanthellae, leaving the reefs bleached white. The coral can slowly recover from a bleaching event, but if conditions remain stressful or if the coral is colonized by other types of algae that keep the zooanthellae at bay, the coral can die.

Andrew Baird from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, who spent 17 days at sea studying the reefs, says that he expects coral mortality in the most affected areas to reach 90 percent. They have already calculated mortality of 50 percent in some areas. “When bleaching is this severe it affects almost all coral species,” he says in the press release, “including old, slow-growing corals that once lost will take decades or longer to return.”

The extent of the bleaching is taking some researchers by surprise. “The coastal area that I study north of Broome has huge tides, and we thought the corals there are tough ‘super corals’ because they can normally cope with big swings in temperature,” says researcher Verena Schoepf from the University of Western Australia. “So, we’re shocked to see up to 80 percent of them now turning snow-white. Even the tougher species are badly affected.”

The bleaching, it seems, is part of a worldwide event likely powered by El Niño and the warming climate, causing the Pacific Ocean temperatures to linger above average. In the future, especially if sea temperatures rise the predicted 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit by 2100, things could get much worse.

There is one piece of good news in the most recent bleaching—the lower third of the reef was largely spared. “This time, the southern third of the Great Barrier Reef was fortunately cooled down late in summer by a period of cloudy weather caused by ex-cyclone Winston, after it passed over Fiji and came to us as a rain depression,” Hughes tells Slezak. “The 2016 footprint could have been much worse.”

There are few short-term solutions for protecting reefs from bleaching, but the Australian Broadcasting Corporation reports that the Queensland Environment Minister—the area most affected by the bleaching—is setting up an emergency conference call with the country’s environment minister and other officials to discuss any actions they can take now.