N. Scott Momaday Built the Foundations of Native American Literature

Smithsonian scholars offer their reflections on the author, who died last week at age 89, and his impact on a new generation of Native writers

:focal(1500x1000:1501x1001)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/22/52/2252f452-a102-4641-bf71-cf295d51a2db/ap24029535243842.jpg)

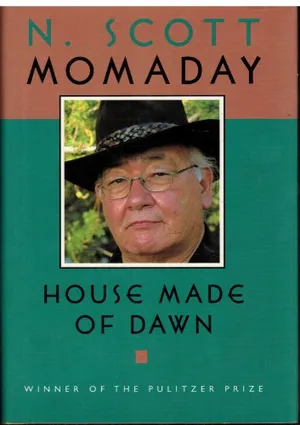

N. Scott Momaday became the first Native American to win a Pulitzer Prize after publishing his first novel, House Made of Dawn, in 1968. The recognition surprised the Kiowa writer, who had always considered himself a poet above all else.

“I don’t think of myself as a novelist,” he told the Los Angeles Times’s Edward Iwata in 1989. “I still feel poetry is the highest form of literature.” Many years after House Made of Dawn’s debut, he still saw its success as an “aberration.”

Momaday died last week at age 89, and he leaves behind an astonishing literary legacy. His barrier-breaking novel paved the way for a new generation of Native American authors, including James Welch, Leslie Marmon Silko, Louise Erdrich and Joy Harjo. His distinctive style, lyrical prose and vivid descriptions make the comparison to poetry apt.

“That’s exactly what it was,” says Kevin Gover, a citizen of the Pawnee Tribe of Oklahoma and the Smithsonian’s under secretary for museums and culture. “It really reads like poetry. … It was quite unique. I’ve seen very little that’s like it before or since.”

House Made of Dawn (Momaday Collection/N. Scott Momaday)

Abel was raised to heed the voice of the land, the changes of the seasons, and the lessons taught by peyote. But once he returned from a foreign war and became exposed to the temptations of the wider world, Abel became a man lost to himself.

Momaday was born on February 27, 1934, in Lawton, Oklahoma. His family’s home “had no electricity, no plumbing,” as he told filmmaker Jeff Palmer in an interview for PBS’ “American Masters” in 2022. “We would be considered at the very bottom of the scale in terms of land and poverty. I came from that by the virtue of good luck and perseverance into a kind of existence that has been visible.”

Both of his parents were teachers as well as artists: His mother, Natachee Scott Momaday, was a writer with English, French and Cherokee heritage. His father, Alfred Momaday, was a Kiowa painter.

When he was a baby, the family relocated to a reservation in Arizona. They moved once again to Jemez Pueblo, New Mexico, when he was 12. Momaday has said that the protagonist of his debut novel is a composite of the troubled individuals he knew as a child at the Jemez Pueblo.

“House Made of Dawn was a very complex emotional [musing] about what it means to be Native in contemporary circumstances,” says Gover, who remembers following the novel’s publication and rise to literary acclaim when he was a child. “[Momaday] was from my part of the country, down in southwest Oklahoma. I remember we were all just kind of amazed—not that we could appreciate when we were kids the quality of his work—but just the fact that somebody like us had produced something that was winning such acclaim.”

After earning a master’s and PhD in English from Stanford University, Momaday went on to teach at several institutions, including the University of California, Berkeley and the University of Arizona, Tucson. According to the Washington Post’s Olesia Plokhii, he wrote House Made of Dawn in the mornings before class.

His debut novel follows Abel, a World War II veteran who returns to his reservation and struggles with alcoholism, identity and adjustment to civilian life. “To tell Abel’s story, Momaday combined modern literary techniques—stream-of-consciousness, a disjointed narrative featuring multiple character perspectives (he acknowledged the influence of William Faulkner)—with a near-mythical, circular structure common in traditional Native American tales,” writes the New York Times’ John Motyka.

A film adaptation of the novel was made in 1972. In 2001, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian obtained the one surviving print of the film, which it has since preserved and made available through its archives. (Several artworks by Momaday and his father are also in the museum’s collections.)

“Momaday was a true inspiration and pioneer, paving the way for Native stories to be vividly told from a Native perspective,” says Dennis Zotigh, a member of the Kiowa Gourd Clan and San Juan Pueblo Winter Clan who works as a writer and cultural specialist at the museum. “Individuals throughout Indian Country took notice that dreams at the highest levels of achievement and recognition are indeed achievable for Native peoples.”

One of those individuals was Sherman Alexie, the famed author best known for The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, who points to Momaday’s status as a multigenre writer celebrated for his fiction, poetry collections, essays and memoirs—and how his sprawling body of work continues to influence Native American writers today.

“I write multigenre because Momaday made it seem like it was the thing that Native American writers do,” Alexie tells the Times. “Like it was a natural part of our identity.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Julia_Binswanger.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Julia_Binswanger.png)