NASA Is Finally Digitizing the Viking Mission’s 40-Year-Old Data

No more microfilm

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/12/d5/12d558d6-af78-47b9-8b22-408aad5b900b/viking_bio_mfilmreaderjpg.jpeg)

When NASA’s Viking I lander touched down on Mars 40 years ago, it was humanity's first toehold on our nearest planetary neighbor. The data scientists gleaned from the lander’s systems provided a historic glimpse of the surface of another planet. Now, decades later, that data is finally getting a facelift as researchers begin the arduous process of digitization, Carli Velocci writes for Gizmodo.

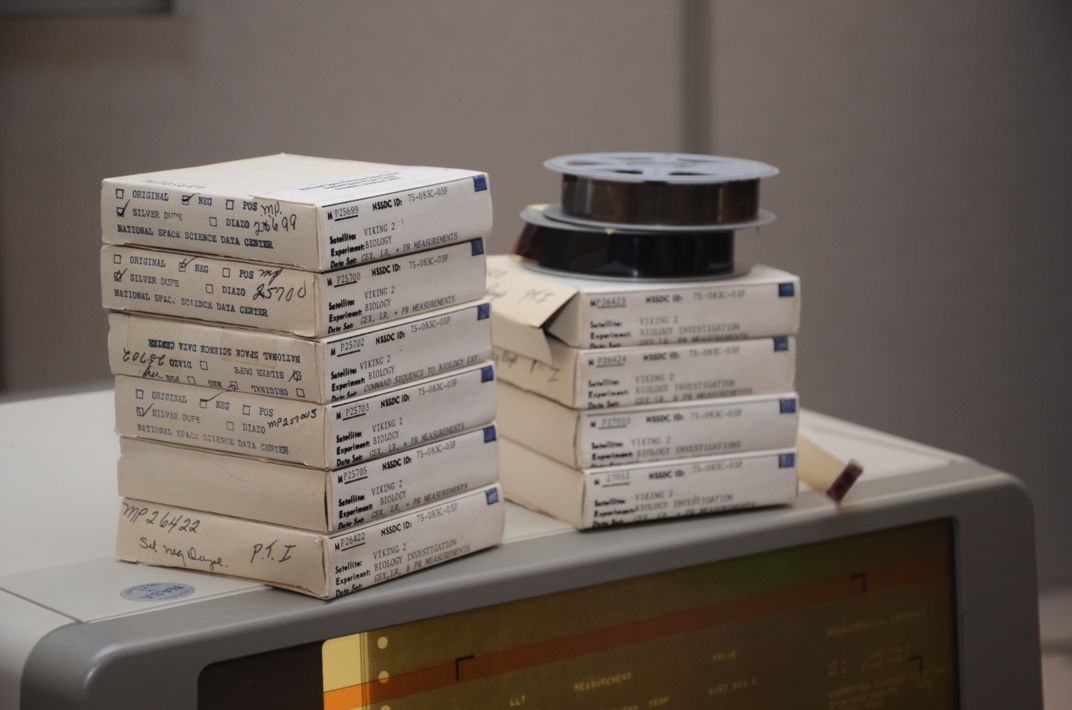

During the 1970s, microfilm was the most common method for archiving scientific data for later study. NASA copied Viking lander data to tiny rolls of microfilm that archivists filed away. But over time, microfilm has fallen out of use.

"At one time, microfilm was the archive thing of the future," David Williams, a planetary curation scientist at NASA’s Space Science Data Coordinated Archive, says in a statement. "But people quickly turned to digitizing data when the web came to be. So now we are going through the microfilm and scanning every frame into our computer database so that anyone can access it online."

For years after the Viking lander went offline, NASA researchers poured over every inch of the probe's high-resolution images and line of data sent. But the microfilm rolls were eventually filed away in the archives and weren’t seen again for nearly 20 years. During the 2000s, Williams got a call from Joseph Miller, a professor of pharmacology at the American University of the Caribbean School of Medicine. Miller wanted to examine data from the biology experiments that the Viking lander conducted, but because the data was still stored solely on microfilm, Williams had to physically search through the archives to find the information, Velocci reports.

"I remember getting to hold the microfilm in my hand for the first time and thinking, 'We did this incredible experiment and this is it, this is all that's left,'" Williams says. "If something were to happen to it, we would lose it forever. I couldn't just give someone the microfilm to borrow because that's all there was."

So Williams and his colleagues got to work digitizing the data, a lenghthy process which will finally make this historic information widely available, including the first images of Mars’ volcano-studded surface and hints of features carved out by flowing water. Images gathered by the Viking I and II orbiters also gave scientists the first close-up look at how Mars’ icy poles changed throughout the seasons, Nola Taylor Redd writes for Space.com.

The Viking data isn’t the only recent digitization effort: Smithsonian Institution and Autodesk, Inc produced a breathtaking 3D model of the Apollo 11 lunar command module and the source code for the Apollo Guidance Computer was just uploaded to the code-sharing site GitHub.

This digitization can not only engage a broader audience, but could help with future discoveries. For example, as data continues to pour in from the Curiosity rover’s Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instruments this older Viking data could provide a richer context to interpret the new finds.

"Viking data are still being utilized 40 years later," Danny Glavin, associate director for the Strategic Science in the Solar System Exploration Division, says in a statement. "The point is for the community to have access to this data so that scientists 50 years from now can go back and look at it."