Two Centuries of Dinosaur Art Come Alive in This Gorgeous New Book

Paleoart traces historic depictions of T. rex, mastodons and other ancient creatures through an artistic lens

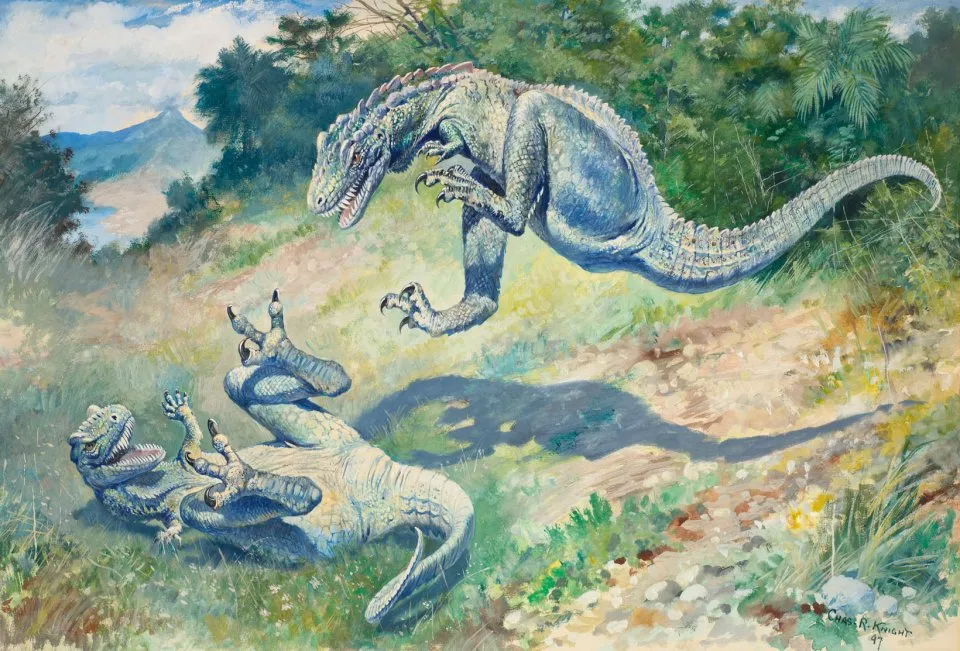

For most dinosaur nerds, it’s not pictures of bone-white skulls or smashed fossils that got them hooked on paleontology. It’s all those awesome paintings of T. rex ripping out the throats of iguanodons, pterodactyls gliding over prehistoric jungles and long-necked titanosaurs slurping up tons of vegetation.

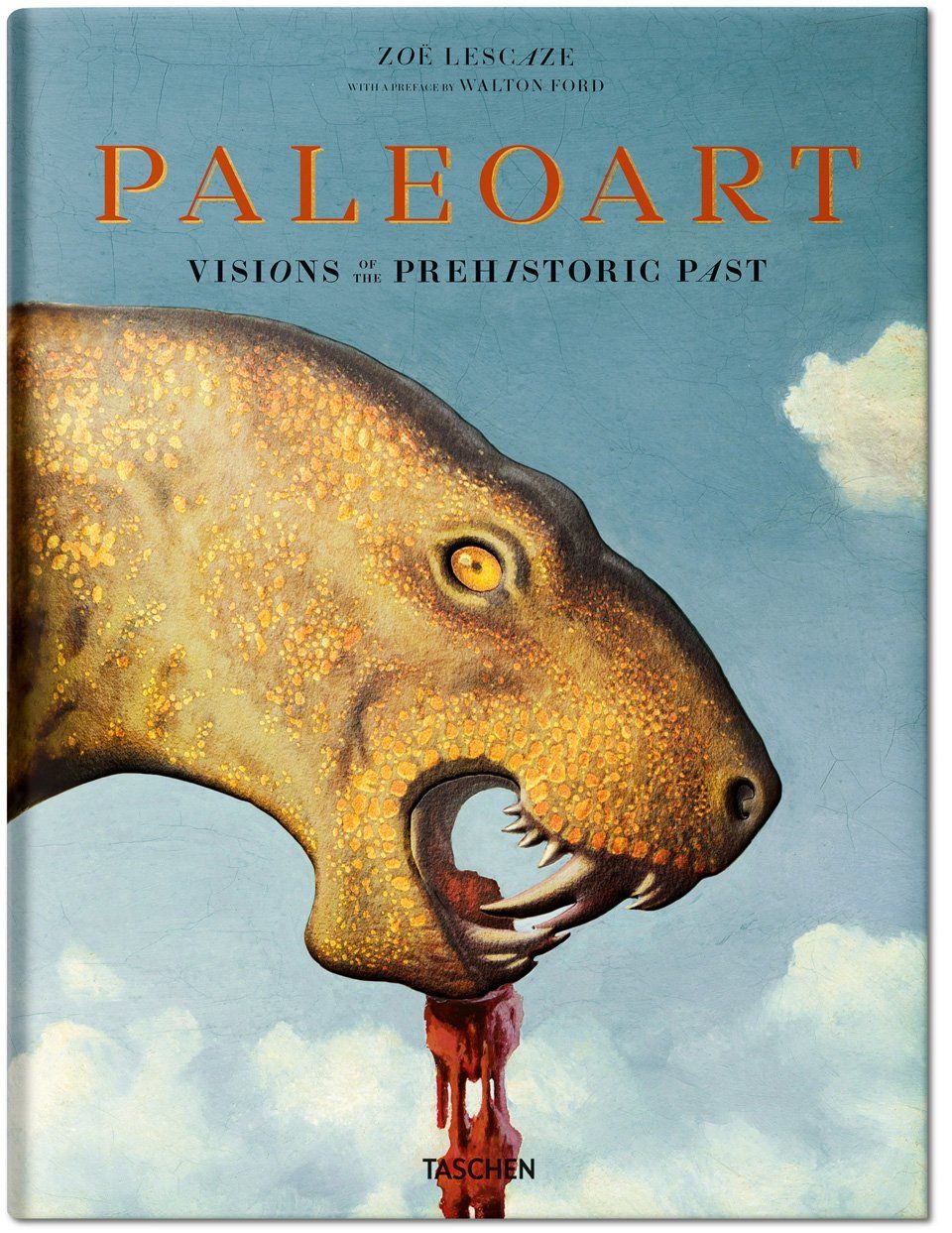

It turns out there’s a name for that genre of mind-blowing images: Paleoart. In Taschen’s new book Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past, writer and art historian Zoë Lescaze explores the history of the art form, which began about 200 years ago and has developed into a critical part of the paleontological world.

The history was the brain child of Lescaze and artist Walton Ford, who contributes a forward and whose paintings are often a weird, satirical take on 19th-century naturalist paintings. Lescaze spent almost four years traveling the United States and Europe tracking the history of paleoart, which was inadvertently first developed in 1830 by scientist Henry Thomas De la Beche, founder of the British Geological Survey. Beche’s friend and neighbor, the fossil hunter Mary Anning, was making incredible finds including the first complete Plesiosaurus, but because of her sex, poverty and lack of education she received little recognition. To bring attention to Anning, Beche painted the watercolor "Duria Antiquior—A More Ancient Dorset," illustrating her finds. Prints of the image became a bestseller.

That popular painting set off the entire genre. At first, Lescaze explains, the works were largely confined to scientific texts. But in 1854, British naturalist and artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins displayed life-sized sculptures of dinosaurs at the Crystal Palace in Sydenham, southeast London, introducing dinosaurs to a mass audience. Americans, too, caught the dinosaur bug, and illustrations of extinct animals soon infiltrated the academic and popular press and became common at natural history museums.

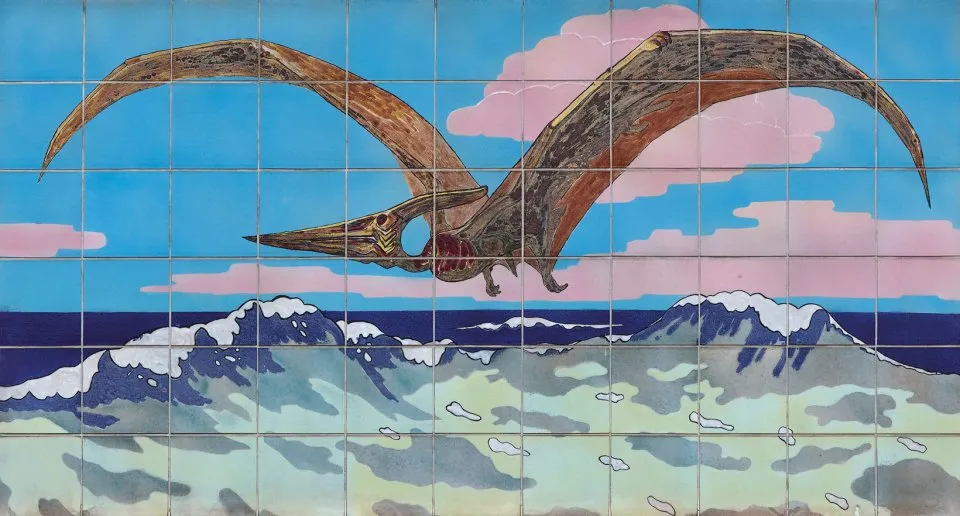

Today, such illustrations are carefully vetted and produced in an almost photo-realistic style. But in the first 150 years of paleoart, artists had much less information to work with, taking some interesting liberties with their subjects and often rendering them in the style of the day, whether that was neo-Impressionism, Art Nouveau or even Social Realism.

“Paleoart went from this sort of niche two-dimensional format to take on every conceivable form,” Lescaze says. “One of the highlights of my research was going to Moscow and finding an enormous concave mosaic that towers several dozen feet above you that was just magnificent with hundreds of animals on this glazed ceramic. In the same museum you have a mural that is golden and pastel sort of like Monet’s water lilies. So it went from small scale origins to these monumental statements and everything in between. That’s what makes the genre so interesting to me."

We asked Lescaze to give us some more insight into the overlooked history of dino-art.

Where did you find all these incredible images?

Paleoart is this sprawling genre that spans the UK, Europe and the United States. The research became this fascinating process of tracking down these more obscure works and unsung artists. There are so many works I found in university archives and natural history museums— oil paintings that were lodged between shelves of saber-toothed tiger skulls that were just beautiful pieces that had never been reproduced or only once in an obsolete science book. So it was a real pleasure to bring some of these artworks to light and perhaps introduce audiences to a genre they may not be familiar with.

Should this stuff be in art museums, or are they just curiosities from paleontology's past?

I think that they are extremely valuable and their value extends beyond their original scientific purposes. They occupy this nebulous niche between scientific illustration and fine art proper. They are not works of fine art, many of them are didactic and designed to relay information. Because they're images of things no human has ever seen, works of paleoart can get discarded in a way that I think images of hawks and herons would not. They are seen as being scientifically obsolete, so why keep them around?

I came to appreciate works of paleoart as being able to tell us a lot about the time in which they were created, the political context and the cultural context. A dinosaur painted in Soviet Russia looks a lot different than one painted in occupied France or Gilded Age America. Because of that they’re worth hanging onto, and if this book has any effect on natural history museums and other institutions on preserving outdated works of paleoart I’d be thrilled.

Has paleoart skewed our view of prehistoric creatures?

I think in the beginnings of the genre in particular paleoart was really controversial. Some scientists didn’t believe it should be made in a lot of situations. [For instance], Labyrinthodont, was a species that Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins sculpted, and he sort of made it like a very wonky-looking frog. Shortly after that, more specimens were found and scientists revised their idea of what it looked like. But [Hawkins'] form kept getting repeated everywhere. [Leading American paleontologist] Othniel Charles Marsh was like, just look at that snafu, let’s not do more of those.

These ideas are hard to eradicate once they’ve lodged themselves in people’s minds. It’s interesting to consider that now. Scientists have had evidence for a while now that many dinosaurs had feathers. But the new Jurassic Park film comes out and none of them have feathers. People are married to the idea that dinosaurs have this crocodilian, leathery, scaly, reptile skin. This is the power of these images.

Do you have a favorite paleoartist?

Yes! Konstantin Konstantinovich Flyorov, this Russian artist who I wasn’t even a little bit aware of when I started this project. Despite being a scientist himself, working in Soviet-era Russia, he really played it fast and loose with the fossil evidence, adapting dinosaurs and prehistoric mammals to his own aesthetic purposes. He was obviously having so much fun through the sheer act of painting, and, of course, this is at a time when proper fine artists were under pretty strict scrutiny from the state, so he inadvertently had almost more room to play by painting within the scientific arena. You see these animals painted in shades of lilac and marigold and these big expressive brushstrokes. They're not depicted as literally scientific or particularly helpful in any educational way. They are just gorgeous paintings, and I think they’re great.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7f/51/7f51eb3b-13f7-4aee-92bf-d2f1b7ef7956/ju_paleoart_p001_1705301541_id_1128568.jpg)