A Black American’s Guide to Travel In the Jim Crow Era

For decades, The Green Book was the black traveler’s lifeline

:focal(375x216:376x217)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/da/4e/da4ec838-244c-43f0-a418-0de810ce73c1/screen_shot_2015-11-02_at_102427_am.png)

For most travelers, a road trip is as easy as packing up luggage, hopping in the car and heading out into the great unknown. But for black Americans, things were never that simple. A series of groundbreaking travel guides from the Jim Crow era have been recently digitized, Gustavo Solis reports for DNAinfo, shedding light on the sobering dangers of segregated travel.

Invented by a postal service worker named Victor Hugo Green, The Green Book was published between 1936 and 1966 as a crucial resource for black travelers. Each guide vetted lists of businesses that would safely serve black travelers—a lifeline in an era of segregated hotels, businesses and "sundown towns" that banned black people. And this year, Solis writes, almost every Green Book has been digitized by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library.

In an extensive background on the guides, CityLab’s Tanvi Misra calls them a creative way for black travelers to "sidestep humiliation (or worse) on their journeys." At times charming and matter-of-fact, and other times chilling, the guides offered insight on everything from changing modes of transportation to the fears and anxieties that black travelers carried during the Jim Crow era. Here are a few important details from the Schomburg Center's collection.

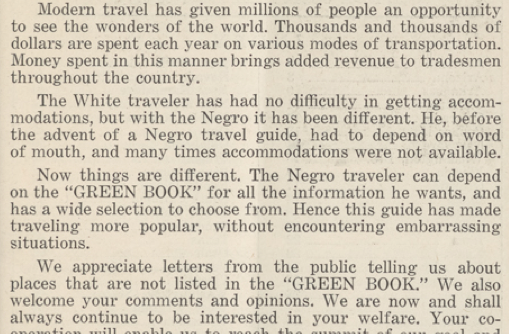

The Green Book had to speak in code:

This excerpt from a 1956 guide hints at the obstacles and dangers that black travelers faced across America. The "embarrassing situations" are clearly a reference to the violence and discrimination inflicted by bigots.

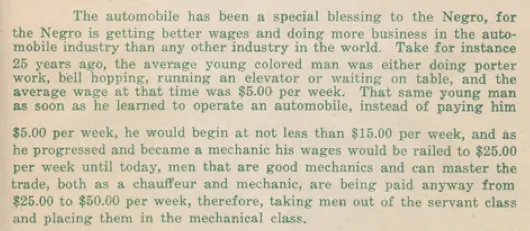

As modes of transportation improved, so did opportunities for black workers:

This excerpt from a 1938 guide shows the promise represented by the automobile—both for black people who wanted to travel and those who sought a means of upward mobility. Later editions of The Green Book also showcased rail, boat and plane travel.

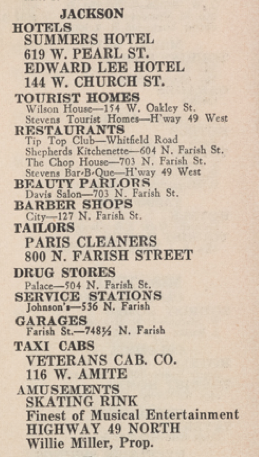

To spot discrimination, just read between the lines:

A typical listing from this 1956 guide lists the types of businesses that welcomed black patrons—and the dearth of beauty parlors, restaurants, drug stores and tailors illustrates how often businessowners refused to serve black customers.

The Green Book contained hope...

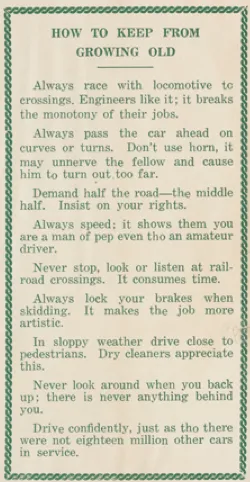

...and humor:

But nonetheless, the guide provided a crucial service:

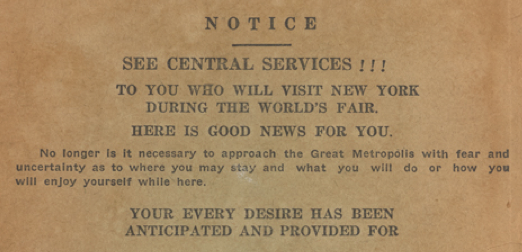

This 1939 advertisement highlights the "fear and uncertainty" that must have accompanied travel, even in (relatively) progressive cities such as New York.

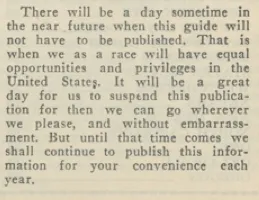

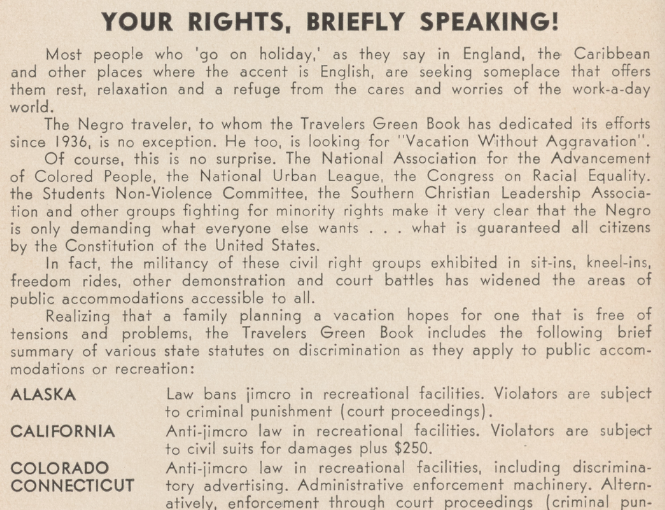

Most of all, The Green Book defended black Americans and their civil rights:

In the 1963-64 edition, readers could refer to a two-page listing of travelers' rights. The guide's focus on civil rights was prescient: within months, the Civil Rights Act forbade the types of discrimination that had inspired The Green Book. In 1966, the last edition of the guide was published.

Though civil rights have been enshrined in law and the Green Book hasn't been printed for decades, discrimination and segregation are still serious, unsolved issues. Just last month, a high-profile lawsuit alleged discriminatory policies in a Houston nightclub. The struggle to make all public places equal for all races continues to this day.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)