Scientists Uncover a “Hidden” Portrait by Edgar Degas

A powerful X-ray unveiled one of the painter’s rough drafts

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5a/0a/5a0a7a7e-aa1e-4e1e-aa73-f75b47993e0e/in_beamline_close.jpg)

For decades, art conservationists have relied on methods like the chemical analysis of miniscule flecks of paint and detailed knowledge of the exact pigments used to restore paintings faded by the years. Now, using a powerful X-ray scanner called a synchrotron, a group of researchers have uncovered an early draft of a portrait by Edgar Degas.

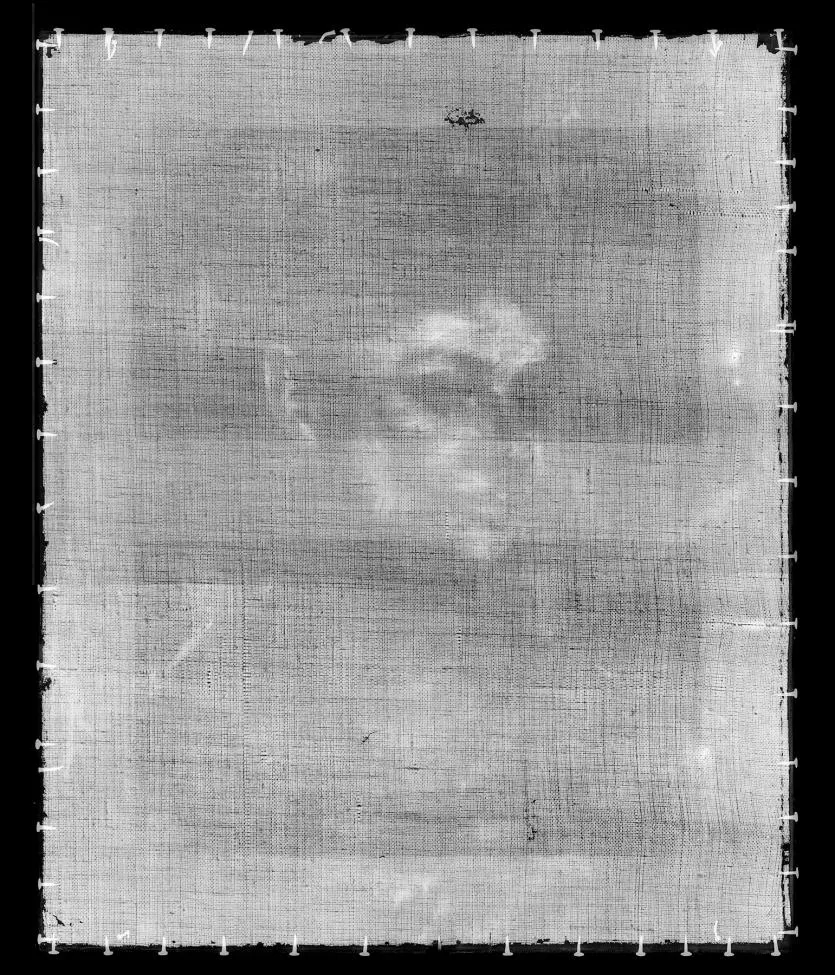

Since 1922, art historians have known that Degas’ Portrait of a Woman was painted on top of an earlier image. The painting was completed in the 1870s, but just a few decades later parts began to fade, revealing a ghostly image lurking underneath. Experts long believed that it was caused by an earlier draft that Degas had made on the same canvas, but traditional restoration methods made it impossible to find out more without destroying the painting. In a new study published in the journal Scientific Reports, however, a team of conservators and scientists were able to peer beneath the paint using the high-powered scanner.

“The X-ray fluorescence technique used at the Australian Synchrotron has the potential to reveal metal distributions in the pigments of underlying brushstrokes, providing critical information about the painting,” study co-author Daryl Howard writes in an email to Smithsonian.com. “This detector allows us to scan large areas of an object such as a painting in a short amount of time in a non-invasive manner.”

The synchrotron can determine the distribution of pigments down to a fraction of a millimeter. Once the scan is finished, the data can be reconstructed by a computer to make full-color digital recreations of the artwork, paint layer by paint layer. Similar to a hospital X-ray machine, the synchrotron uses high-intensity light to take a look beneath the surface of a subject. When scanning the portrait, Howard and conservator David Thurrowgood not only got a look at the long-lost image: they could even see what color it once was.

“The big advantage of a data set like this is that it becomes possible to virtually (digitally) dismantle a painting before a conservation treatment starts,” Thurrowgood writes. “We can immediately see where changes and additions have been made, if there are any unexpected pigments, if there are pigments which are known to degrade in response to particular environments.”

The reconstruction of the underpainting bears a striking resemblance to Emma Dobigny, a woman who posed for several of Degas’ other paintings. But while Thurrowgood and Howard believe the synchrotron can be powerful tools for conservators, it hasn’t been easy to get the art world on board.

“The technique is well outside of the experience level many conventionally trained conservators, and there have been well meaning questions like ‘will it burn a hole in it?’” Thurrowgood writes. “Educating people about the techniques and understanding their fears has been an important issue as these paintings are very valuable, culturally and financially.”

That meant years of testing many kinds of paints before they could turn the machine on a priceless piece by Degas. However, the researchers were able to demonstrate that the technique is even less destructive and provides much better detail than a standard X-ray.

In the past, conservators have had to physically scrape off tiny flecks of the original paint to analyze its chemistry, and even X-rays can produce damaging radiation. A synchrotron scan, on the other hand, allows researchers to figure out a pigment's chemistry without touching the painting, and it uses purer, more powerful light than an X-ray that leaves behind much less radiation.

“Care of art over hundreds of years is a complicated problem, and this is a tool which gives a completely new set of information to use for approaching that problem,” Thurrowgood writes. “The needs of individual artworks can be understood in a way that was not previously possible, and the future survival of the painting can be approached very differently.”