Researchers Studying “Teen Sex” and Flesh-Eating Maggots Win 2016 Golden Goose Awards

Both quirky and important, these studies went against the grain

:focal(298x307:299x308)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/42/5a/425a51a5-8470-4f92-bc59-4ebece7734ec/screwworm_larva.jpg)

Since 2012, the Golden Goose Awards have recognized quirky, federally funded research that's led to major scientific breakthroughs or had significant societal impact. Among this year's winners are researchers delving into the world of flesh-eating maggots and human teenage sexuality, reports Michael Franco for Gizmag.

The awards were created by Representative Jim Cooper, Democrat of Tennessee, as a response to other members of congress’ obsession with “wasteful” science. In particular, the awards act as a rebuttal to Senator William Proxmire of Wisconsin who dished out the so-called Golden Fleece Awards between 1975 and 1988. These awards were given to federally funded research that he believed wasted money.

Among his targets was an $84,000 study funded by the National Science Foundation in 1975 that focused on why people fall in love. He personally objected to the project, writing at the time, “no one—not even the National Science Foundation—can argue that falling in love is a science. Even if they spend $84 million or $84 billion, they wouldn’t get an answer that anyone would believe. And I'm against it because I don't want the answer.”

In 1977, he singled out the Smithsonian for spending $89,000 producing a dictionary of Tzotzil, “an obscure and unwritten Mayan language spoken by 120,000 corn-farming peasants in southern Mexico.”

But this sentiment existed even before the Golden Fleece Awards. Members of Congress repeatedly trotted out one study about the “sex life of screwworm flies” from the 1950s to the 1990s as an example of Washington waste—last week, the researchers were a 2016 Golden Goose winner.

Screwworms were the bane of ranchers in the American South during the early and mid 1900s. Between cattle deaths and battling the screwworms, ranchers lost roughly $200 million per year ($1.8 billion today), according to the award website. The insects laid eggs in small wounds on animals, where their maggots would hatch and eat the animal alive. Screwworms even killed several people.

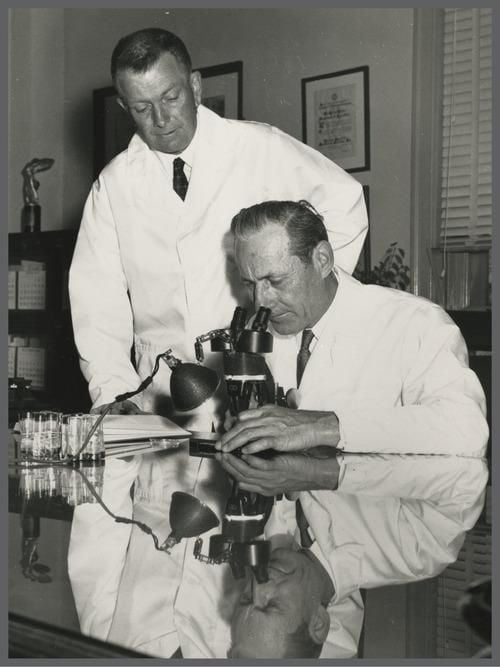

But after studying the sex life of the flies, USDA entomologists Edward F. Knipling and Raymond C. Bushland realized the females mated only once before dying. If they could release large numbers of sterilized male flies, they reasoned, they could cause the fly population to collapse.

This “Sterile Insect Technique” worked; by 1966 the United States was screwworm free. The technique saved ranchers billions of dollars and reduced the price of beef by five percent. The pair received the World Food Prize in 1992.

“Screwworm research may sound like a joke, but it isn’t,” Coooper says. “It saved the livestock industry billions and is giving us a way to fight Zika.”

This year’s other recipients also received their fair share of distaste from Congress. Researchers at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, proposed their study entitled National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health to the National Institutes of Health in 1987—Congress and the media soon dubbed it the “teen sex study.”

They struggled to find funding, but finally suceeded in 1994. The study, known as Add Health, has become a gold standard for basic science.

“The Add Health study has been to social sciences what a major telescope facility would be to the astronomical sciences,” according to the Golden Goose award website. “But unlike a typical telescope, which can observe in only one narrow wavelength range at a time, Add Health has the ability to observe many, many wavelengths of human health and behavior at once.”

Over 20 years, the study's open-source data on the health and sexuality of people in their teens and early 20s has aided in 10,000 research projects, resulting in over 3,000 articles on teenage obesity, HIV and genetics.

A ceremony honoring this year’s recipients will take place at the Library of Congress in September.