These Tropical Fish Have Opioids in Their Fangs

The point isn’t to relieve pain—it’s to kill

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/19/db/19db8f4b-52b2-4a63-baaf-c664fe706c6e/plagiotremus_rhinorhynchos_blue-lined_sabertooth_blenny.jpg)

Blenny fish have always been notable for their big teeth—choppers that give their mouths a demented kind of grin. But it turns out those fangs can do more than chomp down on food. As Steph Yin reports for The New York Times, researchers have discovered that their teeth deliver a three-pronged wallop: venom that has an opioid-like effect inside would-be predators.

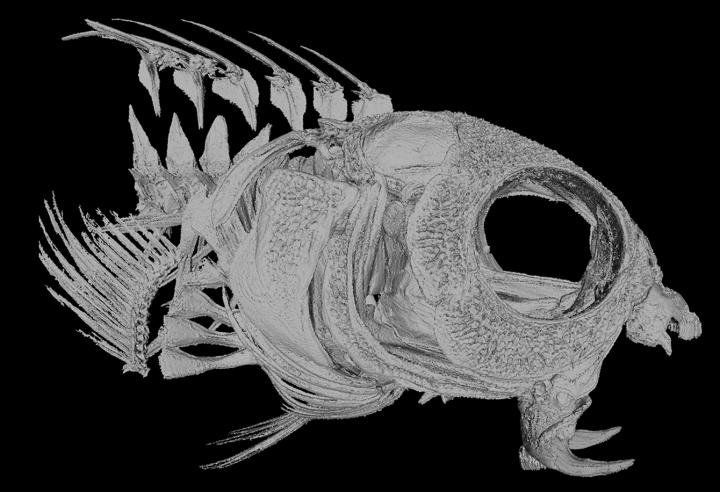

In a new paper published in the journal Current Biology, researchers describe new revelations on how fangblennies—the long-toothed, eel-like cousins of blenny fish—bite. It has long been known that their famed fangs contain venom they use against animals that try to eat them. But until now, it wasn’t clear exactly what it was made of.

It turns out that the venom—and whether fangblennies deliver venom at all—is a bit more complicated than scientists expected. When they studied the jaws of venom-producing blennies, they confirmed a longstanding hypothesis that not all blennies have glands that produce venom. As Yin explains, this lends credence to the theory that as certain species evolved, they grew teeth first, then developed systems to produce venom.

But what’s in the venom? Three toxins that, surprisingly, have never been found in fish before. The venom includes phospholipases, a substance that damages animals’ nerves and that is found in the venom of bees and scorpions, neuropeptide Y, which makes blood pressure drop, and enkephalins, opioids similar to the ones found in heroin and morphine. The venom seems to pack a triple punch: It causes inflammation, disorients and slows down would-be predators, and does it all without freaking out its victims.

The painlessness of the venom was confirmed in tests. When injected with the venom, mice showed blood pressure drops of nearly 40 percent—but didn’t show significant signs of distress. But don’t mistake the venom for a painkiller like fentanyl or oxycodone, Ed Yong writes for The Atlantic.

Though the venom doesn’t seem to hurt—which separates it from the serious pain packed by other venomous fish—it’s unlikely to actually relieve pain in the same way as a painkiller would. Rather, it lowers the victim's distress and knocks them out more effectively than the other components would by themselves.

But how did the researchers get ahold of all that blenny venom to begin with? In a press release, the scientists discuss the labor-intensive process of venom extraction—no easy task given the blennys’ small size (about three inches at the longest) and the small amount of venom they shoot from their fangs. They had to bait the fish with a cotton swab to entice them to take a bite. After putting the angry blenny back in its tank, they would extract the venom from the swab.

"These unassuming little fish have a really quite advanced venom system, and that venom system has a major impact on fishes and other animals in its community,” said Nicholas Casewell of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, who co-authored the study.

It’s not the first time the blenny has made the news. Recently, as Popular Science’s Mark D. Kaufman reports, researchers learned that the fish spends much more time on land than previously thought. Turns out the tiny fish still have the power to surprise—on land and at sea.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)