Vandals Destroyed 8,000-Year-Old Aboriginal Artworks in Tasmania

The priceless rock art is damaged beyond repair

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/30/90/3090a93e-72d2-4429-8951-580cc5e6ddc5/hand-stencil.jpg)

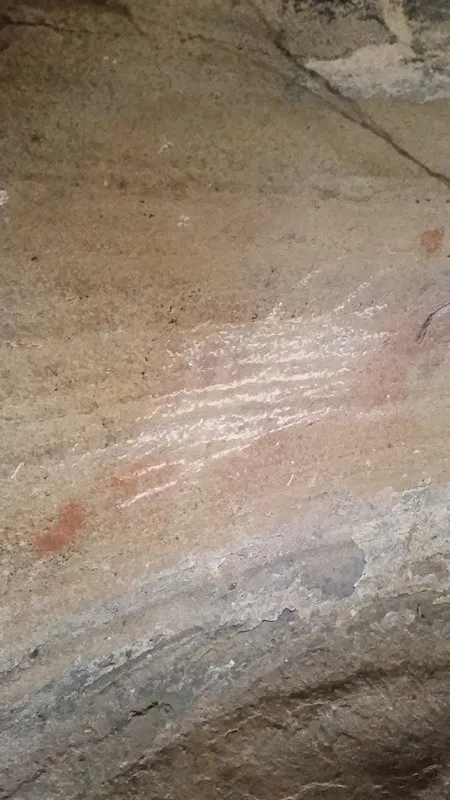

For millennia, Tasmania’s Nirmena Nala rock shelter has preserved a set of stenciled handprints made by the ancestors of Australia’s Aboriginal people. The delicate ocher handprints have withstood the test of time for thousands of years, yet they likely only took minutes to destroy: in late May, conservationists with the Tasmanian Aboriginal Center (TAC) discovered that the precious artworks had been scratched over by vandals.

"They're several thousand years old, priceless and hugely important to the Aboriginal community and somebody has recently gone in their and scratched away the images with a rock to try and deface them." TAC heritage officer Adam Thompson tells Ted O’Connor for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

The hand stencils are located in an upper region of the Australian island’s Derwent Valley. Historians believe that they were made by the Big River people, also known as the teen toomele menennye, and may have been made as they traveled to a nearby meeting site. Many Tasmanian aborigines still consider Nirmena Nala a sacred site, not to mention a precious link to their culture’s history, Sarah Cascone reports for artnet News.

As Clyde Mansell, chairman of the Tasmanian Aboriginal Land Council, tells Calla Wahlquist for the Guardian Australia, the importance of the stencils isn't just about the work itself, but the story that goes with it.

“What makes it sacred is the way in which it was used, and the process that went into making those hand stencils," he says. "If we can’t protect that hand stencil, then we can’t keep it in our interpretation for generations to come.”

The destroyed stencils were some of just a handful of artworks that survived the millennia. What makes their destruction even more devastating for Tasmania’s Aboriginal people is that the vandalism was discovered on May 24 – the day before Sorry Day, a national day of remembrance for the horrendous ways that European colonists treated the Aborigines for centuries, Wahlquist reports.

In a statement, the TAC called for the local Tasmanian government to investigate the handprints’ destruction as a criminal act as well as strengthen laws protecting Aboriginal heritage sites from being destroyed by vandals or by developments.

Nirmena Nala in particular is symbolic of this, as it was partly returned to Tasmania’s Aboriginal people by government-owned electric company, Hydro Tasmania.

Tasmania police are currently investigating the vandalism case. The Tasmanian premier, Will Hodgman, condemned the damage, and called the Aboriginal Relics Act 1875, which sets out penalties for destroying Aboriginal artifacts, outdated and in need of review, Wahlquist reports.

Under the current law, people found guilty of destroying Aboriginal heritage sites can face either a $1,104 fine (USD) or six months in prison.

"Because these penalties are so low under the existing legislation, there's very little deterrent to stop people from going and doing these activities,” Thompson tells O’Connor. "It's priceless and hugely important to the Aboriginal community."