You Can Now Play ‘EmilyBlaster,’ a Video Game Inspired by Emily Dickinson’s Poetry

Players assemble poems by shooting at words in the ‘80s-style adventure

:focal(419x320:420x321)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ea/5a/ea5aaf3b-72ba-4017-8cbf-c5f0e51c16f3/emilyblaster.png)

During her lifetime, Emily Dickinson only published 10 of her nearly 1,800 poems. But she certainly thought about publishing more, once even sending a cryptic letter to an Atlantic Monthly writer asking for career advice.

“Are you too deeply occupied,” she began, “to say if my Verse is alive?”

Today, 136 years after her death, Dickinson is one of America’s most renowned poets—and her verse is very much alive. References to her work proliferate in pop culture, from song lyrics to band names to an entire television series.

The latest addition to that list is “EmilyBlaster,” a free, 1980s-style video game in which players shoot words down from the sky. Before gameplay begins, a poem appears onscreen (the game cycles between “Because I could not stop for Death,” “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain” and “That Love is all there is,” among others). The objective, as a pixelated how-to-play title screen helpfully explains: “Shoot the words in the correct order to assemble the poem!”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1c/62/1c62006b-480b-425b-b8ea-3ebe129651e3/emily_dickinson_daguerreotype_restored.jpeg)

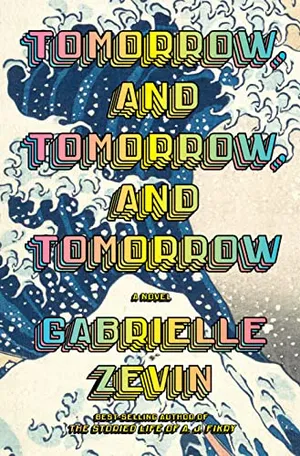

“EmilyBlaster” is based on a fictional game from Gabrielle Zevin’s upcoming novel, Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, reports Literary Hub. The book follows two childhood friends who reconnect later in life and make video games together; one of them, Sadie, creates “EmilyBlaster.” Along with Dickinson’s poetry, the game was inspired by 1980s edutainment games like “Math Blaster!”

“I liked the slight subversiveness of making a game where the object was to shoot poetry,” Zevin tells Literary Hub, “and I thought that Emily Dickinson’s compact verse style and memorable phrasings would make for perfect targets.”

Per the Guardian’s Sarah Shaffi, Zevin’s novel describes “EmilyBlaster” thusly: “Poetic fragments fell from the top of the screen and, using a quill that shot ink as it tracked along the bottom of the screen, the player had to shoot the fragments that added up to one of Emily Dickinson’s poems.” If successful, the fictional player earns points “to decorate a room in Emily’s Amherst house.”

While “EmilyBlaster” exists primarily as promotional material, it isn’t the first attempt to adapt Dickinson’s poetry into a video game. In 2005, organizers of the Game Developers Conference in San Francisco challenged three of the biggest names in the industry to develop a Dickinson-themed game concept, Wired’s Daniel Terdiman reported at the time.

First up was game designer Clint Hocking, who presented an idea he called “Muse.” Players would wander around Dickinson’s home in Massachusetts, collecting items that might have inspired her—like willow trees—and then combining them to create poems. Next was designer Peter Molyneux, whose demo, Wired wrote, “had no fleshed-out concept behind it.”

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow: A novel

In this exhilarating novel by the best-selling author of "The Storied Life of A. J. Fikry" two friends—often in love, but never lovers—come together as creative partners in the world of video game design, where success brings them fame, joy, tragedy, duplicity, and, ultimately, a kind of immortality

Will Wright, creator of “The Sims,” proposed a darker concept (that would not, perhaps, go over as well today) in which people play as Dickinson’s therapist, who the poet interacts with in increasingly volatile ways. She might fall in love with you; she might send you angst-filled messages (“1t is b3tt3r t0 B th3 h4mm3r th4n th3 4nv1L”).

“If she were alive today, she’d be an internet addict,” Wright joked to the crowd, “and she’d probably have a really amazing blog.”

While those games never got made, other real video games based on centuries-old poetry do exist. The 2014 side-scroller “Elegy for a Dead World,” for instance, features three deserted planets, each inspired by a different English Romantic poet: Percy Shelley, John Keats and Lord Byron. Players assume the role of an astronaut exploring the ruins, encountering writing prompts along the way, wrote the A.V. Club’s Derrick Sanskrit. For instance: “You’d like it here; ______. There are worse places that ______.” The gameplay is simply answering these prompts.

The retro-style “EmilyBlaster” is far simpler, consisting of only three levels, all of which can be played in-browser. Still, Zevin contends it is by no means easy.

“EmilyBlaster is a little bit addictive and the right amount hard,” she tells Literary Hub. “It might take you a couple of tries to become the Belle of Amherst.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ellen_wexler.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ellen_wexler.png)