Smithsonian Jazz Expert Gives Liner Notes to the New Miles Davis Biopic

The American History Museum’s James Zimmerman dives into Miles Davis’ sound and style

:focal(613x168:614x169)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bb/3e/bb3e0c67-4766-4f25-9c02-89e3c9783b5b/miles2web.jpg)

“Free booze, free blues, that’s Freddie,” sings James Zimmerman, a jazz scholar and a senior producer at the National Museum of American History, who served as the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra’s producer and executive producer for 11 years.

Zimmerman’s voice mimics the smooth, dreamy instrumentation of “Freddie Freeloader,” found on Miles Davis’ 1959 masterpiece Kind of Blue. He uses the words that lyricist and singer Jon Hendricks penned for the complex arrangement years later. Words so fitting that one could imagine Davis approaching Hendricks to say, “Mother [expletive], what are you doing writing words to my song?”

Leaving the theater after seeing Don Cheadle’s new film Miles Ahead about the raspy-voiced Davis, Zimmerman is singing to prove his point.

“Miles was the greatest singer on the open mouth trumpet that there’s ever been,” he says, echoing the words of jazz great Gil Evans. It’s what first attracted Zimmerman, himself an accomplish vocalist, to Davis’ music in the ’80s.

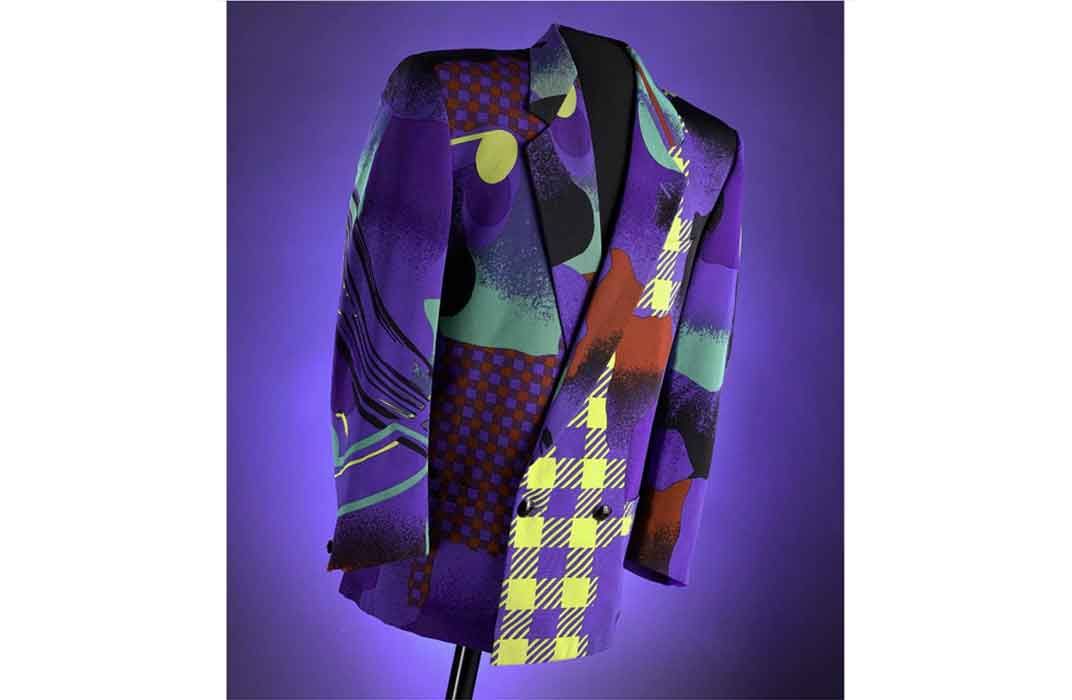

Davis was a middle-class son of a dentist, born into a racially divided America, who once was clubbed on the head by a white policeman for standing outside of a venue where he was performing. In addition to numerous Grammy Awards, Davis has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and even had his work honored by Congress. Different versions of Davis exist side by side: He was an unquestionable genius, who had an electrifying stage presence, a great affection for his children, but also, as Francis Davis writes in the Atlantic, the troubled artist was “peacock vain,” addled by drugs, and, by his own account, physically abused his spouses.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c4/bd/c4bdf4b9-5927-4b8c-be9c-29938a06bfaf/a1000096cweb.jpg)

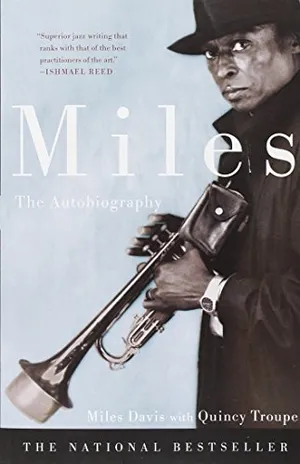

“[B]eing a Gemini I’m already two,” Davis himself wrote in his 1990 autobiography Miles. “Two people without the coke and two more with the coke. I was four different people; two of them people had consciences and two didn’t."

Rather than attempt to reconcile the varied pieces of the legendary jazz trumpeter and bandleader, Cheadle’s film takes the form of an impressionistic snapshot, aiming to tell a “gangster pic” about the jazz great that Davis himself would have wanted to star in.

(Look at this incredible breakdown of Miles' influences in a stunning infographic.)

Zimmerman speculates the film's title, Miles Ahead—also the name of his second album that he did with Evans—alludes to how Davis was always moving forward with his music, from the origins of “cool jazz,” collaborating with Evans in the late 1940s, moving to “hard bop” in the 1950s, changing the game again with modal improvisation in the late ’50s, then taking rock influences to create a fusion sound, as heard in his 1969 jazz-rock album In a Silent Way.

“He was always with the times,” says Zimmerman. “He was listening and he was willing to be a risk taker, without any doubts, without any thoughts of failing. That was the way he was.”

The film grounds itself what has been called Davis' “silent period,” from 1975 to 1980, when the musician was riddled by depression and drugs and couldn’t play the trumpet. It’s an interesting choice, seeing as his sound expressed who he was. “He described his music as his voice,” says Zimmerman. “Sometimes, he wouldn’t talk, he’d just say, ‘Hey let the music speak for itself,’ because he was pouring everything into that.”

In a way, that’s what the movie does, though. The decidedly anti-biopic riffs from one imagined scenario to another, articulating long notes and short trills over a timeline of Davis’ life in the late ’50s and early ’60s. The film often relies on music to explore his relationship with his wife Frances Taylor, as well as his work with musicians John Coltrane and Red Garland and Paul Chambers and Art Taylor.

“The music is hot, the music is very athletic, there’s all kinds of musical gymnastics going on when he meets Frances,” Zimmerman says. A prima ballerina, she was involved with the theater and Broadway. Davis was captivated by her beauty, but perhaps was more drawn to her as an artist. He would go to her shows, and it opened him up to new sounds and influences.

“Broadway, you have a pit orchestra, so he was hearing different things, and I think that got inside of him,” says Zimmerman, guiding Davis away from the hot, energetic music of bebop into the passionate, emotive music that he would create in Sketches of Spain and Porgy and Bess.

While Taylor arguably wasn’t his first wife (Irene Birth, who he had three children with, came first though they had a common-law marriage), nor would she be his last, Zimmerman can see why the film chose to focus on their relationship.

“Frances just sort of got into his heart in a deep way,” says Zimmerman. “That makes me think of [Frank] Sinatra and Ava Gardner and how Ava Gardner dug into his heart and he could never overcome Ava Gardner.”

The silent period comes after Taylor leaves him. Davis was heavily into drugs, was likely dealing with emotional exhaustion from his already 30 years of work as a musical pioneer and was physically worn out. He suffered from sickle-cell anemia and his condition, coupled with the pain from injuries he sustained in a 1972 car crash, had worsened. Still it was a shock to the jazz cats that he stopped playing during that period.

“For someone to be in the limelight for so long to stop recording and leave recording—lots of people talk about that, but they don’t necessarily do it because the music is very much apart of them,” says Zimmerman. “Miles said that and he really didn’t play. The hole was there, but he didn’t play.”

Though the film uses the dynamic between Davis and a fictional Rolling Stone journalist to push Davis to return to the music, it was George Butler, a jazz record executive, who helped persuade Davis to get back into the studio, even sending him a piano. So too did the new music he was hearing.

“The electronic music, the synthesizers, those kinds of things were intriguing to Miles,” says Zimmerman. It took him awhile after being out so long to build up his embouchere.

“That’s everything to a trumpet player,” says Zimmerman. “It took him awhile to get back, but he was listening and playing and working compositions and determining who he could make a statement with.”

In 1989, Zimmerman saw Davis play at Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts in Vienna, Virginia. He performed with a seven-piece band that included saxophonist Kenny Garrett, guitarist Foley and Ricky Wellman, the former drummer for Chuck Brown, Washington D.C.'s renowned “Father of Go Go.” All of these musicians appeared on Davis’ latest album, Amandla. Zimmerman remembers the sound as funky, with some Go-Go influences to it.

“It was sort of him, of the times,” says Zimmerman. “The times were always changing and he was going along with that.”

While the film might not have gotten all of the facts, Zimmerman says it pulled at a greater sense of who Davis was.

“The reality is fiction has foundation in truth, in nonfiction,” says Zimmerman. “I think they got his personality dead on.”